BACKGROUND

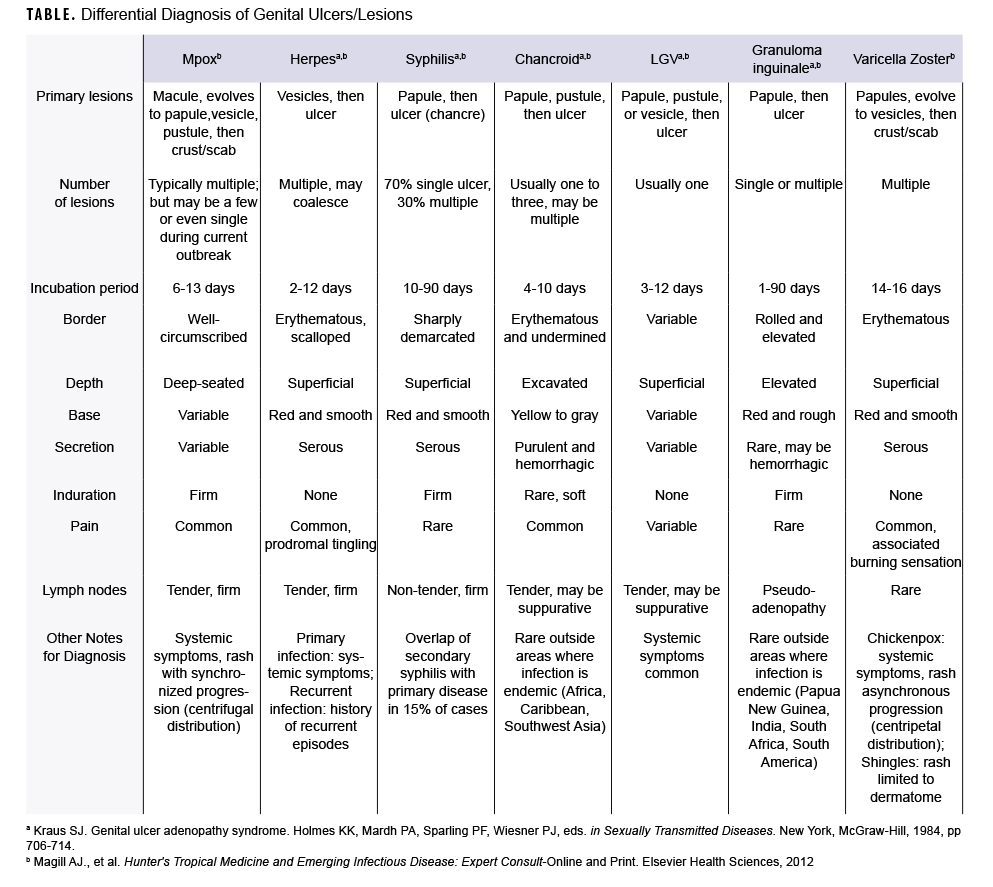

During the current global mpox outbreak, many cases have presented atypically with skin lesions localized to the genital and perianal areas.1,2 The rash associated with mpox can be confused, or occur concurrently, with various sexually transmitted infections. The following text and Table provide a brief comparison of mpox characteristics to those of other infectious causes of genital skin lesions.

METHODS

Literature from 2 textbooks, Genital Ulcer Adenopathy Syndrome and Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases, were reviewed and summarized to compare clinical aspects of infectious disease skin lesions to include: incubation period, lesion characteristics (i.e., type, number, progression pattern, border, depth, induration), and presence of pain or lymphadenopathy.3,4 Mpox skin lesion features recorded in historical and current outbreaks were incorporated as well. Additionally, U.S. and military disease rates (where available) were added to provide epidemiologic context for the frequency of these infectious diseases.

RESULTS

Mpox

Mpox classically presents with fever, myalgia, and lymphadenopathy, followed 1-3 days later by a centrifugal rash that starts on the face and extremities and then disseminates across the body. In the current outbreak, however, early lesions have often been localized to the genital and perineal/perianal areas because of close sexual or intimate contact.1,2 The incubation period is 6-13 days, and lesions typically evolve synchronously through four stages—-macular, papular, vesicular, to pustular—-before scabbing and resolving over the subsequent 2-4 weeks. The 2-10 mm lesions usually are painful, firm, well-circumscribed, and centrally umbilicated.5

Herpes simplex virus

In the U.S., herpes simplex virus (HSV-1 or HSV-2) is the most common cause of genital ulcers, affecting 5.6% of the U.S. adult population, with over half a million new cases annually.6 Among active component service members, the incidence rate of HSV infections from 2013 through 2021 was 23.3 cases per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs), and the rate was 4.5 times higher in females (68.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs) compared to males.7 The incubation period is 2-12 days, and herpetic lesions begin as a cluster of multiple, 2-4 mm vesicles with an underlying erythematous base. These fragile lesions rupture, progressing to painful erosions and shallow ulcerations that gradually heal over 4-10 days.

Syphilis

Syphilis, caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, is the second most common cause of genital ulcers in the U.S.7 Among active component service members, the incidence rate of syphilis was 5.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs from 2013 through 2021.8 The primary syphilis lesion (chancre) begins as a solitary, firm papule that quickly becomes a painless ulcer with well-defined margins and indurated base. The incubation period is 10-90 days, and the ulcer heals spontaneously within 3-6 weeks. Although the maculopapular rash associated with secondary syphilis usually appears 4-10 weeks after the primary chancre, primary and secondary syphilis findings overlap in 15% of cases.9

Chancroid

The gram-negative bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi causes chancroid, which is rarely diagnosed in the U.S., with less than 10 cases reported annually.10 Sporadic outbreaks occur in Africa and the Caribbean.9,11 The incubation period is 4-10 days, and begins as an erythematous papule that rapidly evolves into a pustule and erodes into a deep ulcer. These painful 1-2 cm ulcers have clearly demarcated borders with a friable base covered by a gray or yellow exudate. It is common to have multiple ulcers.

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV)

LGV is predominantly found in tropical or subtropical regions, but outbreaks have been reported among men who have sex with men in Europe, North America, and Australia.12,13 The true incidence rate of this bacterial infection in the U.S. and among service members is unknown because national reporting of LGV ended in 1995. LGV is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serovars L1, L2, or L3. A 2011 report of surveillance data from multiple sites in the U.S. found that less than 1% of rectal swabs obtained from military service members positive for Chlamydia trachomatis were positive for LGV serovars.14 LGV infection has 3 stages: ulceration, regional lymphadenopathy, anogenital fibrosis. The incubation period is 3-12 days, and the primary stage of LGV is characterized by small, painless genital papules or ulcers that heal spontaneously within a few days.

Granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis)

Donovanosis is a rare disease caused by the intracellular bacterium Klebsiella granulomatis and is sporadically found in Asia, South Africa, and South America.9 In a recent MSMR surveillance snapshot on donovanosis among active component service members, only 50 incident cases were identified between 2011 and 2020, with 3-10 cases reported annually.15 It is characterized by painless, progressive ulcers on the genitals or perineum that are highly vascular, have a beefy red appearance, and easily bleed. The incubation period ranges from 1-90 days.

Varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox/shingles)

The incidence rate of chickenpox infections in the U.S. dramatically decreased following the implementation of the national varicella vaccination program in 1995, with a 97% decline from pre-vaccine years.16 Among active component service members, only 37 confirmed and 205 possible cases were reported between 2016 and 2019.17 Chickenpox presents as multiple red papules in a centripetal distribution, involving the scalp, face, and trunk, then spreading across the body (including the genital area). The incubation period is 14-16 days with prodromal symptoms (fever, headache, malaise, decreased appetite) prior to rash appearance. The itchy lesions progress asynchronously from papules to vesicles (1-4mm) and then rupture and crust or scab over during a final 5-10 days.18 Reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (shingles) presents as multiple, small vesicles in a unilateral dermatomal distribution and may be associated with severe pain, pruritus, and/or burning sensation in the affected dermatome. Vesicles crust over in 7-10 days.

EDITORIAL COMMENT

While mpox is not traditionally known as a sexually transmitted disease, in the current outbreak transmission has primarily been reported with intimate or close sexual contact. This highlights the importance of understanding the differential diagnosis for infectious causes of genital skin lesions, especially in a predominantly young adult military population. Summarizing other infectious diseases provides a framework to more expeditiously diagnose and treat mpox. The table and accompanying text in this article provide a succinct review to compare and contrast these infectious diseases. Additionally, reports of disease rates of each infection provide perspective for the U.S. military population. As the mpox outbreak is new and evolving, case rates are not yet well described. Infectious genital skin lesions and other sexually transmitted infections may occur concurrently, thus testing for co-infections is important to quickly identify all pathogens and appropriately treat individuals.

Disclaimer

The contents described in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or the Department of the Air Force.

Author affiliations

Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland (Lt Col Hsu); Air Force Medical Readiness Agency, Falls Church, VA (Lt Col Sayers).

REFERENCES

- Minhaj FS, Ogale YP, Whitehill F, et al. Monkeypox outbreak—-nine states, May 2022. MMWR. 2022;71(23):764-769.

- Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries—-April–June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022:387:679-691.

- Kraus SJ. Genital ulcer adenopathy syndrome. In: Holmes KK, Mardh PA, Sparling PF, Wiesner PJ, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York, McGraw-Hill; 1984:706-714.

- Magill, AJ, Ryan ET, Hill DR. Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease: Expert Consult—-Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012.

- Macneil A, Reynolds MG, Braden Z, et al. Transmission of atypical varicella-zoster virus infections involving palm and sole manifestations in an area with monkeypox endemicity. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(1):e6-e8. doi:10.1086/595552

- Kreisel KM, Spicknall IH, Gargano JW, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among U.S. women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(4):208-214. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001355

- Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012:85(3):254-262.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Department. Update: sexually transmitted infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2012-2020. MSMR. 2021;28(3):13-22

- Dombrowski JC, Celum C, Baeten J. Chapter 43: Syphilis. In: Sanford CA, Pottinger PS, Jong EC, eds. The Travel and Tropical Medicine Manual. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2017:535-544.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Table 43. Chancroid--Reported Cases and Rates of Reported Cases by State/Territory in Alphabetical Order, United States, 2015-2019. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2019/tables/43.htm. Published April 12, 2022. Accessed July 29, 2022.

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021;70(4):1-187. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1.

- de Voux A, Kent JB, Macomber K, et al. Notes from the field: cluster of lymphogranuloma venereum cases among men who have sex with men--Michigan, August 2015–April 2016. MMWR. 2016;65:920–921. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6534a6

- Simms I, Ward H, Martin I, Alexander S, Ison C. Lymphogranuloma venereum in Australia. Sex Health. 2006;3(3):131-133. doi:10.1071/sh06039

- Hardick J, Quinn N, Eshelman S, et al. O3-S6.04 Multi-site screening for lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) in the USA. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(Suppl 1):A82-A82. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2011-050109.136

- Daniele D, Wilkerson T. Surveillance snapshot: donovanosis among active component service members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2011-2020. MSMR. 2021;28(12):22.

- Lopez A, Harrington T, Marin M. Chapter 22: Varicella. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, 14th ed. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/varicella.html. Published September 20, 2021. Accessed September 3, 2022.

- Williams VF, Stahlman S, Fan M. Measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella among service members and other beneficiaries of the Military Health System, 1 January 2016–30 June 2019. MSMR. 2019;26(10):2-12.

- Hall E, Wodi A P, Hamborsky J., et al., eds. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 14th ed. Washington, DC, Public Health Foundation, 2021.