Abstract

From the inception of the Special Warfare Training Wing in fiscal year 2019 through 2021, 753 male, enlisted candidates attempted at least 1 Assessment and Selection and did not self-eliminate (i.e., quit). Candidates were on average 23 years of age. During candidates’ first attempt, 356 (47.3%) individuals experienced a musculoskeletal (MSK) injury. Among the injuries, the most frequent type was nonspecific (n=334/356; 93.8%), and the most common anatomic region of injury was the lower extremity (n=255/356; 71.6%). When included in a multivariable model, older age, slower run times on initial fitness tests, and prior nonspecific injury were associated with both any injury and specifically lower extremity MSK injury.

What are the new findings?

During Assessment and Selection, 356 (47.3%) of candidates suffered an MSK injury. The most frequent type was nonspecific (n=334/356; 93.8%) and the most common anatomic region of injury was the lower extremity (n=255/356;

71.6%). Older age, slower run times, and prior nonspecific injury were associated with injury during the course.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

MSK injuries are costly and continue to be the leading cause of medical visits and disability in the U.S. military and are more prevalent in the special operations community than in conventional military forces. Identifying predictors of injury in this population can inform clinicians and staff regarding the provision of prevention and rehabilitative strategies to reduce this risk.

Background

Musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries are costly and the leading cause of medical visits and disability in the U.S. military.1,2 Within training environments, MSK injuries may lead to a loss of training, deferment to a future class, or voluntary disenrollment from a training pipeline, all of which are impediments to maintaining full levels of manpower and resources for the Department of Defense. Additionally, injuries sustained during training often lead to chronic conditions or impairments at a later time during a warfighter’s career.3 Previous studies have found that special operations forces experience higher MSK injury rates than conventional forces,4 and more so in training environments.5 Although previous investigations have studied MSK injury rates in samples of Air Force (AF) special operators,4,6 to date, there are no studies that have explicitly characterized the incidence of MSK injuries in the AF Special Warfare Training Wing (SWTW) pipeline.

The AF SWTW was established in fiscal year 2019 to assess, select, and train individuals to become one of 4 AF Special Warfare (AFSPECWAR) specialties: Tactical Air Control Party (TACP), Pararescue, Combat Control, and Special Reconnaissance. With the exception of TACP, each of these specialties require a candidate to successfully complete an arduous 16-day Assessment & Selection (A&S) course. Due to the nature of this assessment process, MSK injuries are common. However, no studies have reported the incidence of MSK injuries during A&S. Thus, the purpose of this study was to report the incidence of MSK injury during the 16-day SWTW A&S; and identify factors that were associated with experiencing an MSK injury during this period.Methods

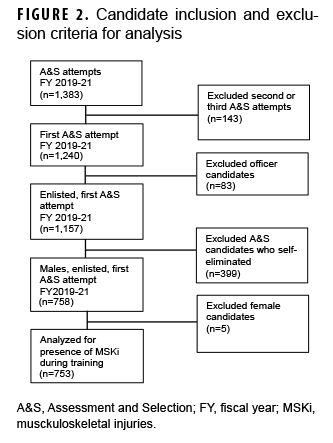

The cohort included enlisted AFSPECWAR candidates who first attempted A&S during fiscal years 2019–2021 and did not voluntarily disenroll (i.e., quit). Officer candidates were excluded from the analysis due to differences in their previous training prior to A&S. Female candidates were excluded due to the small number of candidates (n=5), which precluded comparisons by sex. Data for analysis were routinely collected throughout the pipeline leading up to the start of A&S (Figure 1). The Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB)7 was administered before the candidates entered Basic Military Training (BMT). Results from baseline fitness tests and body composition factors were collected at the start of the Special Warfare Candidate Course (SWCC). The Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test was administered at the start of A&S.

Data regarding MSK injuries were extracted from the Military Health System (MHS) Management Analysis and Reporting Tool. The direct care outpatient system was searched for encounters within the stated timeframes for the cohort. The 10th Revision of the International Classification of Disease (Clinical Modification) codes were categorized according to a matrix that assigned an injury type and region to each injury using a taxonomy adapted from a previously published work.3,8 Briefly, the matrix broadened the inclusion of non-specific, overuse, and other MSK conditions that can also impact completion of training. For the coding of prior MSK injury, the timeframe of 6-months prior to starting A&S was selected to align with the timeframe of a candidate entering BMT, at which point relevant healthcare records are collected within the MHS.Covariates were selected for analysis based on 2 specific rationales; (1) explanatory covariates including baseline fitness, body composition, and prior injury status that are known from the literature to have an association with risk of injury, and (2) exploratory covariates including anthropometric measurements, cognitive factors, and age that are routinely collected by the SWTW and discussed internally as potentially related to injury risk.

The injury surveillance period included the 16-day course as well as an additional 7 days following course termination, when students were permitted to rest with little to no formal training conducted. The surveillance period was extended in this way because many candidates will not report their injuries until the training concludes. In addition, providers are often unable to document injuries in the electronic medical record system until the course finishes. Chi-square tests and independent samples t-tests were used for bivariate testing of categorical and continuous factors, respectively, for differences between candidates with and without MSK injury during A&S. Where appropriate, the Mann-Whitney U, and Fisher’s exact tests were also employed. Binary logistic regression was used to build multivariable models to identify factors associated with MSK injury during A&S. In addition, binary logistic regression was also employed to identify factors associated with lower extremity MSK injury specifically, the most common anatomic site of injury. For multivariable modeling, complete-case analysis was employed. The TRIPOD checklist was followed for model development only (i.e., not validation).9

The presented final binary logistic regression models were exploratory in nature and future validation will be necessary. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses. Odds ratios (ORs) adjusted ORs (AORs), and their associated confidence intervals (CI) are reported with a threshold of p<.05 for univariate significance and a threshold of p<.10 was used to determine retention of variables in the logistic regression models. The final logistic regression model was selected that obtained optimal goodness of fit and area under the receiver operating curve.

Results

Overall, 753 male enlisted candidates attempted A&S at least once and did not self-eliminate during fiscal years 2019 (4 classes), 2020 (5 classes), or 2021 (6 classes) (Figure 2). Candidates were, on average, 23 years of age at the start of their first A&S attempt. During candidates’ first A&S attempt, 356 (47.3%) experienced an MSK injury; of those candidates, the most frequent injury type was nonspecific (n=334/356; 93.8%) (Figure 3), and the most common anatomic region of injury was the lower extremity (n=255/356; 71.6%) (Figure 4).

Any type of MSK injury

Bivariate analyses revealed that initial fitness, age, BMI, and prior MSK injury were statistically significantly associated with injury during candidates' first A&S attempt (Table 1). The only baseline fitness measure significantly associated with injury during A&S was slower 1.5 mile run times. Body fat mass, lean body mass, dry lean mass, percent body fat, and skeletal muscle mass, were not significantly higher for candidates who were injured, compared with those who were not injured. Slightly more than one-half of the candidates (n=393; 52.2%) had suffered any prior MSK injury type, and a significant proportion of these candidates also suffered injury during A&S (64.0% vs 41.6%; p<.001). More specifically, prior nonspecific, nerve, sprain or joint damage, strain or tear, and systemic or genetic MSK conditions were all associated with a higher frequency of injury during A&S. Injuries that occurred at all anatomic sites other than the torso were associated with a higher frequency of any type of injury during A&S.

The average age of candidates injured during A&S was significantly higher (24.2 years, SD=4.1) compared with those who were not injured (23.0 years, SD=3.8). Other tested cognitive factors, including highest academic level, overall IQ, and ASVAB test scores were not significantly associated with injury during A&S in bivariate analyses.Multivariable analysis

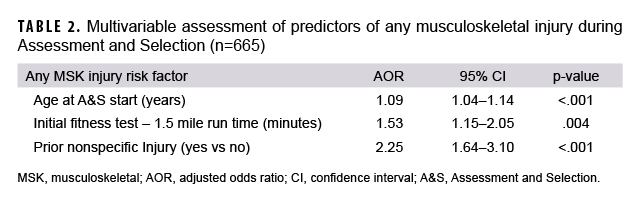

In an adjusted binary logistic regression model, factors that were retained as associated with injury during A&S included age at A&S start (AOR=1.09; 95% CI: 1.04–1.14; p<.001), 1.5 mile run time on initial fitness test (AOR=1.53; 95% CI: 1.15–2.05; p=.004), and prior nonspecific injury (AOR=2.25; 95% CI: 1.64–3.10; p<.001) (Table 2).

In an adjusted model, factors that were retained as associated with lower extremity injury during A&S included age at A&S start (AOR=1.05; 95% CI: 1.01–1.10; p=.018), 1.5 mile run time on initial fitness test (AOR=1.41; 95% CI: 1.05–1.90; p=.023), and prior nonspecific injury (AOR=1.91; 95% CI: 1.37–2.67; p<.001) (Table 3).

Editorial Comment

The purpose of this study was to report the incidence of MSK injuries in a 16-day rigorous SWTW A&S, and to identify factors associated with suffering an MSK injury. This is the first characterization of MSK injury in a SWTW A&S population, finding 47.3% of candidates suffered an MSK injury, with the most frequent type as nonspecific (93.8%; of those injured). Knapik et al previously described medical encounters during a U.S. Army Special Forces A&S course, reporting 38% of the candidates experienced one or more injuries during the 19-20 day period.10 The high percentage of injury among both cohorts is an indication of the rigorous requirements incurred by trainees in short periods of times under extremely challenging circumstances.

The lower extremity was identified as the most common anatomic region of injury during A&S (71.6%; of those injured). This finding is consistent with Lovalekar et al, who also reported lower extremity MSK injury as the most common region in Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) Qualification Training Students.11 However, both findings should be interpreted with caution, as these values may be underestimates due to potential under-reporting.12

When put into a multivariable model, older age, slower run times on initial fitness tests and prior nonspecific injury increased the likelihood of any musculoskeletal injury and, more specifically, lower extremity MSK injury. Although BMI was significant on the univariate analysis, the variable did not meet the criteria for retention in the final adjusted model. These findings are similar to previous studies of similar populations that have found low levels of physical fitness, slower run time or history of a previous injury13–15 were all associated with sustaining MSK injury. Age, poor muscular endurance, and slower run times have also been observed to be reliable indicators of future acute injuries in U.S. Army Infantry, Armor, and Cavalry basic trainees during initial entry training (IET),16 but only performance deficits in running tests were correlated with ‘overuse’ MSK injuries in their cohort. Several additional observations of military IET samples have reported similarities in MSK injury risk associated with poor aerobic capacity test performances, which does indicate a distinct and historical association between aerobic fitness and MSK incidence early in military service.17–19

A novel aspect of this manuscript analyzed IQ and ASVAB scores for association with MSK injury. These potential covariates were selected a priori based on literature demonstrating relationships between neurocognition, biomechanics20 and early screening21 to detect MSK injury. Additionally, literature documents components of ASVAB scores as a reliable predictor for graduation in an Army course,22 supporting the current study hypothesis to investigate an association between ASVAB scores and MSK injury during A&S. However, no significant relationship was found for either IQ or ASVAB scores.

There are inherent limitations to the collected data and analysis. First, this work is retrospective, and as such is subject to selection bias. Additionally, there was no delineation between injuries and training loss for the candidates, and therefore the results should be interpreted with caution. Also, the vast majority of candidates who voluntarily disenrolled during A&S did so within the first 2 days of A&S (internal data), and since this would potentially significantly impact the injury exposure, these candidates were excluded from analysis. However, as some of these candidates may have disenrolled due to an unspecified injury, this would impact the findings of this study.

Finally, all candidates were cleared medically to transition from BMT to SWCC, and again from SWCC to A&S. It is assumed at the start of SWCC and A&S that MSK injuries have been resolved, and candidates have a ‘clean bill of health’. However, due to the inherent nature of MSK injuries, challenges with diagnosis, and candidates’ propensity to not report injuries that could delay the completion of their training, it is possible that some MSK injuries prior to A&S are indistinguishable from new injuries during A&S. Regardless, increased surveillance of candidates who had prior injuries is still warranted for injury prevention during A&S whether they are new or persistent. Future work is planned to examine the detailed timing and severity of MSK injuries, as well as elimination rates and types, throughout the training pipeline.

In conclusion, MSK injuries continue to be costly and the leading cause of medical visits and disability in the U.S. military and are more prevalent in the special operations community than in conventional military forces. To increase the readiness and longevity of operators, continued efforts are required to reduce MSK injury risk. The findings from this project highlight the increased risk of MSK injury in this population and provide further evidence for the scientific community to continue to develop appropriate prevention, screening, and rehabilitative strategies to reduce that risk and increase the health and readiness of members in the Special Warfare community.

Author Affiliations

Special Warfare Human Performance Squadron, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio TX.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. William C Scott PhD for his contributions in data retrieval and management.

References

- Grimm PD, Mauntel TC, Potter BK. Combat and noncombat musculoskeletal injuries in the US military. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2019;27(3):84–91.

- Teyhen DS, Shaffer SW, Goffar SL, et al. Identification of risk factors prospectively associated with musculoskeletal injury in a warrior athlete population. Sports Health. 2020;12(6):564–572.

- Molloy JM, Pendergrass TL, Lee IE, Chervak MC, Hauret KG, Rhon DI. Musculoskeletal injuries and United States Army readiness Part I: overview of injuries and their strategic impact. Mil Med. 2020;185(9-10):e1461–e1471.

- Warha D, Webb T, Wells T. Illness and injury risk and healthcare utilization, United States Air Force battlefield airmen and security forces, 2000-2005. Mil Med. 2009;174(9):892–898.

- Stannard J, Fortington L. Musculoskeletal injury in military Special Operations Forces: a systematic review. BMJ Mil Health. 2021;167(4):255–265.

- Lovalekar M, Johnson CD, Eagle S, et al. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among US Air Force Special Tactics Operators: an economic cost perspective. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1): e000471.

- Cudeck R. A structural comparison of conventional and adaptive versions of the ASVAB. Multivariate Behav Res. 1985;20(3):305–322.

- Hauschild V, Hauret K, Richardson M, Jones BH, Lee T. A Taxonomy of Injuries for Public Health Monitoring and Reporting. Army Public Health Command. 2018.

- Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BJOG. 2015;122(3):434–443.

- Knapik JJ, Farina EK, Ramirez CB, Pasiakos SM, McClung JP, Lieberman HR. Medical encounters during the United States Army Special Forces Assessment and Selection Course. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e337–e343.

- Lovalekar M, Perlsweig KA, Keenan KA, et al. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries sustained by Naval Special Forces Operators and students. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20 Suppl 4:S51–S56.

- Hotaling B, Theiss J, Cohen B, Wilburn K, Emberton J, Westrick R. Self-reported musculoskeletal injury healthcare-seeking behaviors in US Air Force Special Warfare personnel. J Spec Oper Med. 2021;21(3):72–77.

- Kaufman KR, Brodine S, Shaffer R. Military training-related injuries: surveillance, research, and prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(3 Suppl):54–63.

- Shwayhat AF, Linenger JM, Hofherr LK, Slymen DJ, Johnson CW. Profiles of exercise history and overuse injuries among United States Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) recruits. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(6):835–840.

- Teyhen DS, Shaffer SW, Butler RJ, et al. What risk factors are associated with musculoskeletal injury in US Army Rangers? A Prospective prognostic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(9):2948–2958.

- Sefton JM, Lohse KR, McAdam JS. Prediction of injuries and injury types in Army basic training, infantry, armor, and cavalry trainees Using a Common Fitness Screen. J Athl Train. 2016;51(11):849–857.

- Psaila M, Ranson C. Risk factors for lower leg, ankle and foot injuries during basic military training in the Maltese Armed Forces. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;24:7–12.

- Wentz L, Liu PY, Haymes E, Ilich JZ. Females have a greater incidence of stress fractures than males in both military and athletic populations: a systemic review. Mil Med. 2011;176(4):420–430.

- Knapik J, Ang P, Reynolds K, Jones B. Physical fitness, age, and injury incidence in infantry soldiers. J Occup Med. 1993;35(6):598–603.

- Porter Ke’la, Quintana C, Hoch M. The relationship between neurocognitive function and biomechanics: a critically appraised topic. J Sport Rehabil. 2020;30(2):327–332.

- Berg Rice VJ, Connolly VL, Pritchard A, Bergeron A, Mays MZ. Effectiveness of a screening tool to detect injuries during Army Health Care Specialist training. Work. 2007;29(3):177–188.

- Grant J, Vargas AL, Holcek RA, Watson CH, Grant JA, Kim FS. Is the ASVAB ST composite score a reliable predictor of first-attempt graduation for the U.S. Army operating room specialist course? Mil Med. 2012;177(11):1352–1358.