To the Editor

We read with interest the brief report regarding the prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection in basic military trainee blood donors by Kasper and colleagues in the November 2021 issue of the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR),1 an update of a previous similar report.2 The authors are commended for providing timely and actionable information to assess a possible rise in the burden of HCV among new military trainees. We agree that these data should be considered when evaluating whether the U.S. military should institute HCV screening in the Air Force and Army at the time of accession, as has been implemented in the Navy and Marine Corps since 2013.

Our main point of clarification focuses on the case definition employed by Kasper et al. Specifically, the authors stated that “A positive test for HCV antibody in addition to either a positive HCV RNA or EIA indicates active infection.”1This was further reflected in their methods, which stated that confirmed cases were “positive HCV RNA or EIA.” However, the diagnostic guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state that only an RNA test confirms the diagnosis of active HCV infection; a second antibody test (i.e., EIA) does not.3 A positive HCV-antibody test may indicate: 1) current (active) HCV infection (acute or chronic); 2) past infection that has resolved; or 3) a rare false positive. For this reason, national HCV guidelines state that “A test to detect HCV viremia is therefore necessary to confirm active HCV infection and guide clinical management, including initiation of HCV treatment.”4 The CDC and Department of Defense case definitions for confirmed cases of HCV also include a positive HCV antigen test, HCV antibody conversion (from negative to positive) within a 12 month period, or a documented negative HCV antibody or RNA test followed by a positive RNA test within 12 months.5-7 While all 6 cases described in the report were actually confirmed by RNA (Maj K. Kasper, written communication, 11 March 2022), it is worth clarifying this point to ensure MSMR readership understanding.

This discrepancy around HCV case confirmation likely results from the differences between: 1) the CDC recommendations for HCV diagnosis, and 2) the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommendations and standards for blood donation screening. CDC guidelines for the diagnosis of HCV state that a positive initial antibody test followed by a negative RNA test indicates “no current HCV infection,” but that “additional testing as appropriate” should be performed.3 In its guidance as to when additional testing is appropriate, CDC states that “to differentiate past, resolved HCV infection from biologic false positivity for HCV antibody, testing with another HCV-antibody assay can be considered.” Other national guidelines state that “although additional testing is typically unnecessary...the HCV-RNA test can be repeated when there is a high index of suspicion for recent infection or in patients with ongoing HCV infection risk.”4

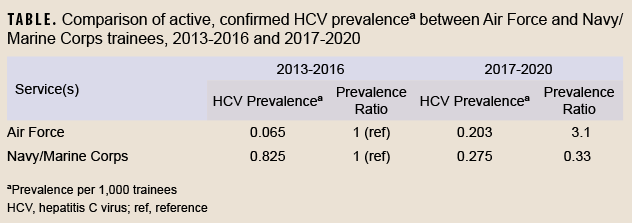

In contrast, the FDA states that for blood donors in the same scenario (i.e. who have a positive initial antibody test followed by a negative RNA test), a “second, different licensed donor screening test or an approved or cleared diagnostic test for anti-HCV” should be performed.”8 Furthermore, whereas CDC recommendations generally interpret a positive second antibody test as evidence of a past, resolved HCV infection, FDA recommendations for this scenario state that “if the result is repeatedly reactive for anti-HCV…the test results for the donation are considered positive...”8 Such a positive result per FDA recommendations considers the blood product “positive” for transfusion purposes. The permanent deferral of individuals with a negative RNA test but a positive second HCV antibody test from blood donation reflects the more cautious approach taken for blood donation screening compared to diagnostic testing. The FDA justifies this position by stating that although the majority of these individuals will have resolved infections, some may have “a chronic persistent infection with transient or intermittent low-level viremia.”8The Armed Service Blood Program guidelines for transfusion screening and blood donation follow the FDA’s approach.9This different approach used for blood donation may explain why Kasper et al. considered a second EIA as a confirmatory test for active infection. Despite these differences, the conclusions from Kasper et al. remain the same and valid, since all 6 occurrences in their case series were confirmed by RNA. Of further note, since the Navy and Marine Corps routinely screen basic military trainees, the prevalence of HCV infection can be assessed directly in those services without the concern for limited generalizability from using blood donors noted in previous Air Force reports.1,2 These data are routinely collected by the Navy Bloodborne Infection Management Center (NBIMC). The prevalence of confirmed HCV infection in Navy and Marine Corps basic trainees between 2017 and 2020 was 0.275 per 1,000 trainees (83 cases among 302,163 trainees), similar to the prevalence of 0.203 per 1,000 Air Force blood donor trainees (6 cases among 29,615 trainees) reported by Kasper et al. during the same interval (NBIMC, unpublished data, August 2022). The consistency between these rates suggests that estimates of HCV infection from trainee blood donors may be generalizable to the full population of Air Force trainees.

The prevalence of HCV among trainees was also of similar magnitude as that seen among a random sample of deployed service members between 2007 and 2010 (0.43 per 1,000 service members).10 However, the temporal trends in HCV prevalence were quite different between the Air Force and the Navy/Marine Corps, as shown in the Table. While the prevalence of HCV infection among Air Force trainees in 2017-2020 was substantially higher (prevalence ratio=3.1) than that observed in 2013-2016, the prevalence in Navy and Marine Corps trainees was instead lower (prevalence ratio=0.33) in the later time period (NBIMC, unpublished data, August 2022).1,2 The causes and significance of differing recent trends among the services are unclear, but may be due to the effects of temporal trends, birth cohort, age, the absence of trainee screening procedures in any of the services prior to 2013, or random variability.

As noted by Kasper and colleagues, adult screening for HCV is recommended by CDC and other nationally recognized expert organizations.1 The Army and Air Force should consider implementing universal screening at accession in order to conform to these recommendations, improve health and readiness, and ensure the safety of the “walking blood bank.” The use of blood donations for surveillance purposes can be highly useful, particularly in the absence of the availability of other relevant data. However, when interpreting such data, attention should be paid to assessing any differences from standard diagnostic approaches, differences from standard criteria used to define cases, and the potential for volunteer bias and limited generalizability.

Author affiliations

Department of Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (COL Mancuso); Navy Bloodborne Infection Management Center, Bethesda, MD (CAPT Teneza-Mora).

Disclaimer

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private ones of the author and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense or the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

References

- Kasper KB, Holland NR, Frankel DN, Kieffer JW, Cockerell M, Molchan SL. Brief report: Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infections in U.S. Air Force basic military trainees who donated blood, 2017-2020. MSMR. 2021;28(11):9-10.

- Taylor DF, Cho RS, Okulicz JF, Webber BJ, Gancayco JG. Brief report: Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections in U.S. Air Force basic military trainees who donated blood, 2013-2016. MSMR. 2017;24(12):20-22.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(18):362-365.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: HCV Testing and Linkage to Care. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/evaluate/testing-and-linkage. Accessed 14 March 2022.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Armed Forces Reportable Medical Events: Guidelines and Case Definitions. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2020/01/01/Armed-Forces-Reportable-Medical-Events-Guidelines. Accessed 15 May 2021.

- Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS): Hepatitis C, Acute, 2020 Case Definition. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-c-acute-2020/ Accessed 15 March 2022.

- Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS): Hepatitis C, Chronic, 2020 Case Definition. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-c-chronic-2020/. Accessed 15 March 2022https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-c-chronic-2020/ Accessed 15 March 2022.

- Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Further Testing of Donations that are Reactive on a Licensed Donor Screening Test for Antibodies to Hepatitis C Virus: Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/116353/download. Accessed 14 March 2022.

- Armed Services Blood Program. BPL 20-09, Attachment 1: Armed Services Blood Program Guidelines for Relevant Transfusion-Transmitted Infection Screening, Donor Deferral and Notification, and Lookback Processes for Blood Donation. In Washington, DC: Department of Defense; June 2020.

- Brett-Major DM, Frick KD, Malia JA, et al. Costs and consequences: Hepatitis C seroprevalence in the military and its impact on potential screening strategies. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):398-407.