What Are the New Findings?

Incidence of sepsis hospitalizations is increasing in the active component. The highest rates were seen in female service members, the oldest and youngest age groups, and recruits. The incidence rate gap between male and female service members increased over time. There was a sharp decline in sepsis diagnoses in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Sepsis is a severe, life-threatening condition that poses an increasing risk to U.S. military members. It leads to long hospital stays and recovery periods and detracts from readiness and deployability. Sex disparities in sepsis rates highlight a women's force health protection issue that requires further investigation.

Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the incidence and trends of sepsis hospitalizations in the active component U.S. military over the past decade. Between Jan. 1, 2011 and Dec. 31, 2020, there were 5,278 sepsis hospitalizations of any severity recorded among the active component. The overall incidence was 39.8 hospitalizations per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs). Annual incidence increased 64% from 2011 through 2019, then dropped considerably in 2020. Compared to their respective counterparts, rates were highest among female service members, the oldest and youngest age groups, and recruits. The gap in sepsis hospitalization rates between female and male service members increased over the surveillance period. Pneumonia was the most commonly co-occurring infection, followed by genitourinary infections. Among female service members, genitourinary infections were more commonly diagnosed compared to pneumonia. The most common non-infection co-occurring diagnoses were acute kidney failure and acute respiratory failure. This study demonstrates an apparent sex disparity in sepsis rates and further study is recommended to understand its cause.

Background

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.1 Septic shock is a more severe manifestation of the same process with hypotension and inadequate tissue perfusion. Septicemia is an older term no longer in clinical use because it is nonspecific and blends the concepts of sepsis and bloodstream infection which are not necessarily synonymous.

The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) were published in 2016.1 Prior to this, the term sepsis was used for a dysregulated host response without organ dysfunction and severe sepsis was used if organ dysfunction was present. Sepsis-3, however, makes organ dysfunction a component of sepsis, thereby making severe sepsis a superfluous term. Severe sepsis is, however, still used in administrative coding practices.

Sepsis and septic shock are common causes of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality requiring rapid, protocol-based treatment, usually with broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics. Understanding the epidemiology of sepsis and septic shock as well as the underlying infections and co-occurring conditions is vital for recognition of risk factors and implementation of appropriate empiric treatment protocols.

Recent studies have found 50 million cases of sepsis (of any severity) worldwide and over 1 million cases in the U.S. in 2017, among which 189,623 deaths occurred.2 Despite evidence of increased incidence of sepsis in the general population, the current impact of this condition on the U.S. military is largely unknown. The only military surveillance study, published in 2013, reviewed the annual incidence of septicemia among active component service members for the years 2000 –2012.3 This study found an overall incidence of 13.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs. Incident cases increased dramatically over the surveillance period, in particular from 2004 through 2012 when there was a 570% increase in the annual incidence rate of septicemia as a primary diagnosis, likely attributable to changes in definitions and coding practices.3 In addition, there were differences in sepsis rates between demographic groups, with higher overall rates of septicemia in female compared to male service members, the youngest and oldest individuals (age <20 and 45+) compared to those aged 20–44, Marines compared to members of other services, recruits in basic training compared to non-recruits, junior enlisted compared to senior enlisted service members, and senior officers compared to junior officers.3

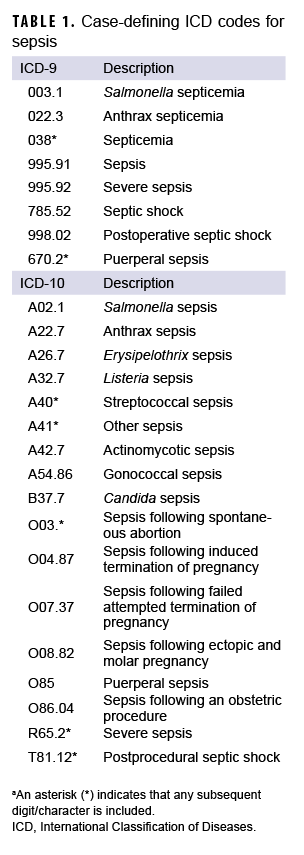

In addition to changes in clinical definitions and criteria, the Military Health Care System (MHS) transitioned from using the 9th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) to the 10th revision (ICD-10) for coding purposes in October 2015. ICD-10 did not include septicemia, but added more specific codes which include the causative organisms (when known). In light of major substantive changes to the definition of sepsis, both clinical and administrative, updated surveillance data on the impact of sepsis on the U.S. military are needed. This report summarizes the frequencies, rates, and trends of incident diagnoses of septicemia, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock among members of the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces over the past decade. It also describes frequencies of diagnoses of sepsis, infectious agents, and co-occurring conditions during hospitalizations with incident diagnoses of septicemia, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock.

Methods

This study included all U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps members who served in the active component at any time between Jan. 1, 2011 and Dec. 31, 2020. All data used in this analysis were derived from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which maintains electronic records of all actively serving U.S. military members' hospitalizations and ambulatory visits in U.S. military and civilian (contracted/purchased care through the MHS) medical facilities worldwide. Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) Contingency Tracking System (CTS) records for service member deployments are also maintained in the DMSS, which include the dates and countries of deployment.

Several studies have attempted to validate and optimize case definitions for sepsis using ICD-10 data, and have recommended using broad search criteria.4,5 In this study, incident sepsis cases of any severity (i.e., septicemia, sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock) were identified from records of hospitalizations that included any diagnostic codes (ICD-9 and ICD-10) specific for these conditions (Table 1). Cases from hospitalization records were included if they had any of these codes recorded in any diagnostic position. An individual could account for multiple incident cases if there were more than 14 days between the dates of consecutive incident case-defining encounters. Co-occurring conditions were identified by ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes from the incident hospitalizations with a concurrent sepsis-related code.

Data were obtained from DMSS for 9 covariates: age group, race/ethnicity group, sex, branch of service, rank, geographic region, deployed status, recruit status, and military occupation. An Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division algorithm based on age, rank, duty location, and time since entry into military service was used to determine recruit basic training status. Deployed status was defined as being currently deployed on the date of diagnosis or deployed within the past 30 days to any known location (deployments to unknown locations or bodies of water were excluded).

Incidence rates were calculated as incident cases per 100,000 p-yrs. Overall incidence rates as well as rates stratified by covariates were calculated for both the total surveillance period and for each calendar year of surveillance. For the purpose of describing frequencies of diagnoses for sepsis, infections, and co-occurring conditions, ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were placed in three categories: 1) sepsis codes which included all case-defining codes in Table 1; 2) infection codes which included codes for co-occurring infections; and 3) co-occurring diagnoses which included other codes that do not fit into the other 2 categories and could represent risk factors for sepsis, sequelae from sepsis, or be unrelated to sepsis. Based on clinical experience some codes which did not specify an infection were included in the infection codes category because they are potentially causal for sepsis (e.g., acute pancreatitis, non-infective gastroenteritis and colitis). All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

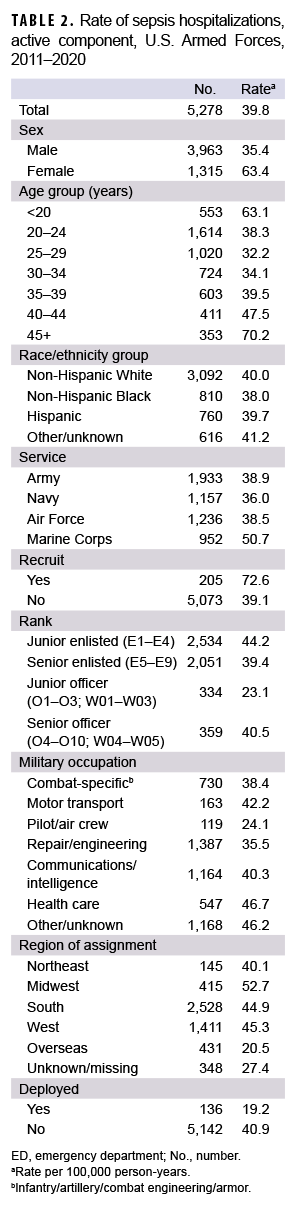

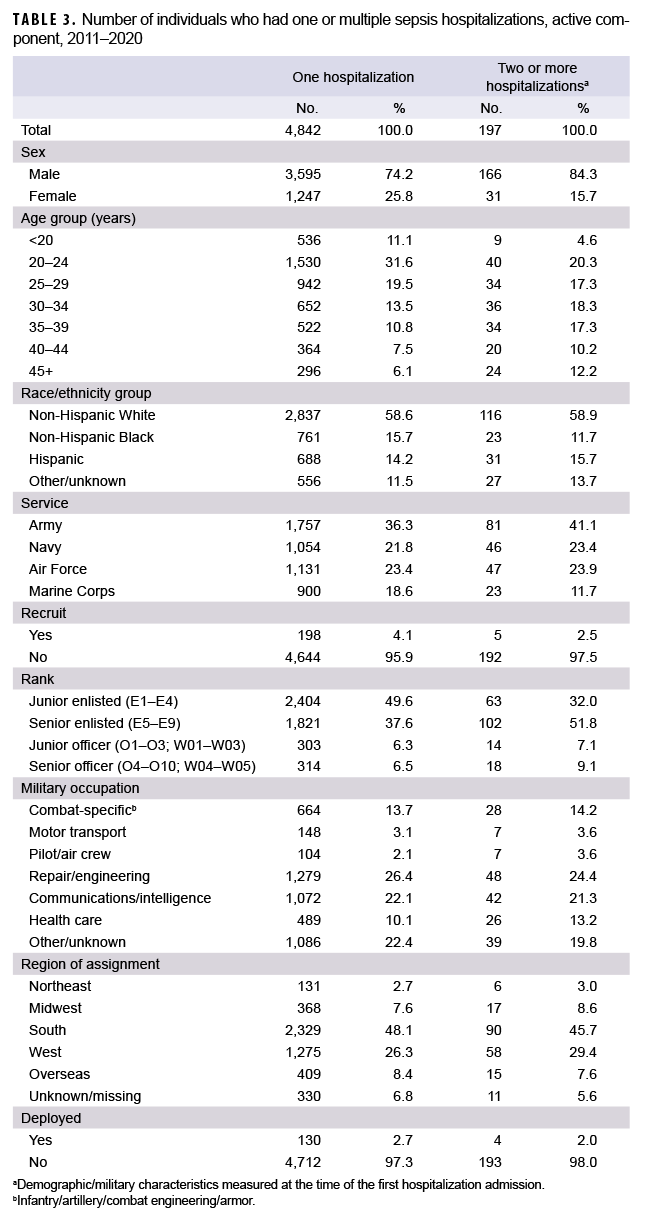

Overall, there were a total of 5,278 incident hospitalizations with any sepsis diagnosis (i.e., sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, septicemia) during the study period (Table 2). These 5,278 hospitalizations occurred among 5,039 unique individuals. A total of 4,842 service members had 1 hospitalization during the study period, and 197 service members had 2 or more hospitalizations (Table 3). Service members who had multiple hospitalizations during the study period were more likely to be male (84.3%) and older (39.6% aged 35 or older), compared to those with only 1 hospitalization during the study period (74.2% male and 24.4% aged 35 or older).

The crude overall incidence of sepsis hospitalization was 39.8 cases per 100,000 p-yrs and there was a 64% increase in annual rates from 2011 through 2019 (31.1 cases to 51.0 cases per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). In 2020, the crude incidence of sepsis declined to 42.0 cases per 100,000 p-yrs (data not shown).

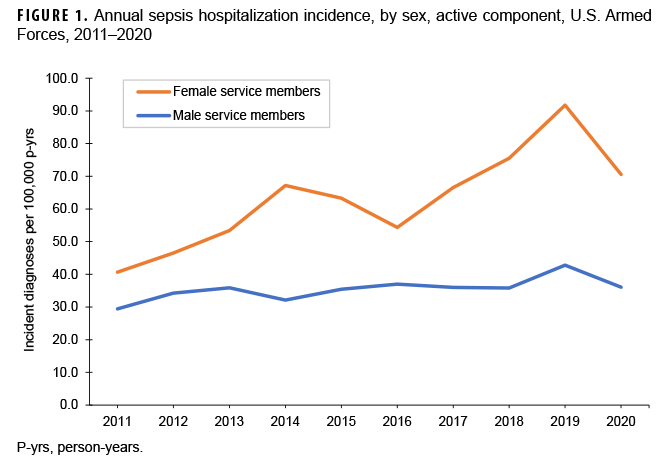

Incidence was higher among female than male service members (63.4 vs 35.4 cases per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively; incidence rate ratio [IRR]=1.8). The incidence of sepsis among male service members was relatively consistent over time, while that among female service members showed an increasing trend, peaking in 2019 at a rate of 91.8 cases per 100,000 p-yrs (Figure 1). Overall incidence was highest among those under 20 years old (63.1 cases per 100,000 p-yrs) and older than 45 years (70.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs) compared to those aged 20 –45. There were no pronounced differences in overall incidence rates of sepsis diagnoses between race/ethnicity groups.

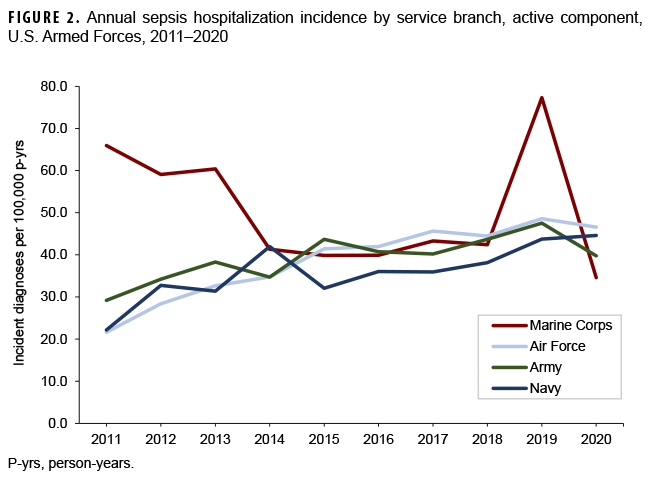

Marines had a higher overall incidence compared to their counterparts in the Army, Navy, or Air Force (Table 2). This was primarily due to higher annual incidence in Marines from 2011 through 2013. After 2013, annual rates were similar and stable among the branches, except for 2019 when Marines again had a higher rate (Figure 2). Recruits had nearly double the overall incidence of non-recruit active component members (72.6 vs 39.1 cases per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively, IRR=1.9). Junior officers had the lowest overall rate of incident sepsis diagnoses. Pilots and air crew had the lowest overall incidence rate of sepsis compared to other occupations, while health care workers had the highest.

Among active component service members stationed within the continental U.S., those in the Northeast had lower overall rates compared to the Midwest, South, and West. Service members stationed overseas had considerably lower rates than those in any continental U.S. regions. Deployed or recently deployed service members had a lower overall incidence rate than those who were non-deployed.

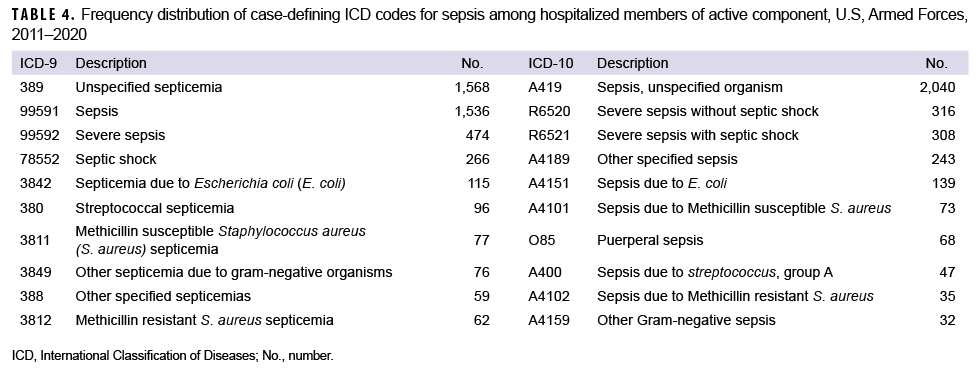

Case-Defining Codes

The most frequent case-defining ICD-9 diagnoses (Table 4) were unspecified septicemia and sepsis, followed by severe sepsis and septic shock. Combination codes containing specific infectious organisms were used infrequently. The most frequent case-defining ICD-10 diagnoses were sepsis of unspecified organism, severe sepsis without shock, severe sepsis with shock, and other specified sepsis. Combination ICD-10 codes were also used infrequently.

Among all sepsis combination codes, Escherichia coli (E. coli) was used most frequently under both ICD-9 and ICD-10, followed by Streptococcus, methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), and unspecified gram-negative organisms under ICD-9, and MSSA and puerperal sepsis under ICD-10.

Infections

The most common co-occurring infections based on ICD-9 codes were pneumonia with unspecified organism, unspecified pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection, postoperative infection, and cellulitis of the leg (Table 5). Based on ICD-10 codes, the most frequent infections were pneumonia from unspecified organism, acute tubulo-interstitial nephritis, unspecified urinary tract infection, unspecified E. coli infection, and unspecified tubulo-interstitial nephritis. While pneumonia was commonly diagnosed in both male and female service members, urinary tract infections, pyelonephritis, and pyonephrosis were much more frequently seen in female service members whereas cellulitis was much more common in males. Some codes such as puerperal sepsis were only applicable to female service members, although these accounted for a small proportion of sepsis codes in female service members. Pneumonia was by far the most frequently diagnosed infection in both recruits and non-recruits. Codes for cellulitis were more frequently documented in recruits than non-recruits, while pyelonephritis and urinary tract infections were more frequently documented in non-recruits (data not shown).

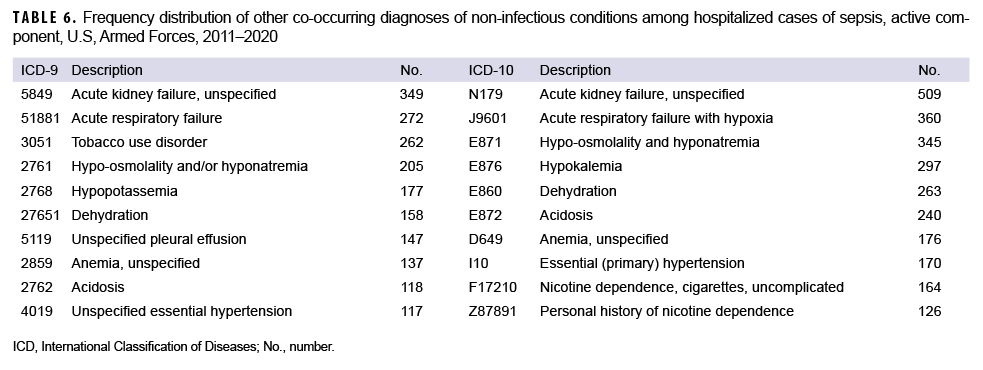

Co-Occurring Diagnoses

The most frequent co-occurring diagnoses other than infections based on ICD-9 codes were unspecified acute kidney failure, acute respiratory failure, tobacco use disorder, hypoosmolality and/or hyponatremia, and hypopotassemia (Table 6). Under ICD-10, the most frequent co-occurring diagnoses were unspecified acute kidney failure, acute respiratory failure with hypoxia, hypo-osmolality and hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and dehydration. Male and female service members had similar co-occurring diagnoses, though respiratory failure and tobacco use disorder were less frequently diagnosed in female service members (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

Overall, annual sepsis rates increased between 1 Jan. 2011 and 31 Dec. 2020, with the exception of a sharp decrease in 2020. The highest overall rates were seen among female service members, the oldest and youngest age groups, and recruits. The incidence rate gap between male and female service members widened over the surveillance period. Overall, pneumonia was the most commonly coded co-occurring infection, followed by various infections of the urinary tract with genitourinary infections being more common in female service members and pneumonia and cellulitis more common in male service members. Various codes for pneumonia, followed by cellulitis, made up the majority of coded infections among recruits, with very few genitourinary infections. The most common co-occurring diagnoses were acute kidney failure and acute respiratory failure.

Studies using administrative data to assess the incidence of sepsis in the general U.S. population have produced results that have varied widely depending on the spectrum of sepsis evaluated (e.g., all sepsis vs only severe sepsis) and the coding case definition used.6 Reported sepsis rates in the U.S. are higher than active component rates (U.S. in 2017 had 254.9 cases per 100,000 population compared to 39.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in the active component), though the results are not directly comparable because of significant demographic differences between the general U.S. and military populations.2 Despite the varying results in the overall annual rates, U.S. population-based studies did show consistent findings in certain demographic groups. They consistently show higher rates of sepsis among males, which is the inverse of this study's findings in the active component. The reasons for this difference are unknown, but this trend has persisted since 2006 and deserves further study.3 Infections that are specific to female service members such as pregnancy-related infections were seen, but in relatively small numbers. Another major difference seen in this study was the lack of racial disparities with regards to sepsis incidence. In contrast, U.S. population-based studies have consistently reported higher sepsis rates among non-Hispanic Blacks compared to non-Hispanic Whites. One possible explanation for this difference is universal health coverage and access to care among the active component population. Additionally, some underlying risk factors for more severe infections such as diabetes mellitus and chronic lung disease, which disproportionately affect the American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic communities, are less prevalent in the active component than in the U.S. civilian population.7

There are several major challenges in current epidemiological surveillance of sepsis, particularly stemming from changing clinical definitions and coding practices, in addition to the lack of universal acceptance of any specific set of definitions. Sepsis-3 moved away from using systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and began using the more comprehensive sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, but there is still no specific diagnostic definition nor any specific laboratory test that universally confirms the diagnosis of sepsis.8 Likely due to this study's broad case definition, there were no drastic changes in sepsis rates between 2015 and 2016 despite the new clinical definitions and ICD-10 turnover around that time. For cases prior to the transition to ICD-10, ICD-9 codes consistent with septicemia, sepsis, or septic shock were used, but codes for bacteremia or other infection which did not imply sepsis were omitted, which explains the slight difference in ICD-9 codes used here compared to prior articles looking at active component military members.

Use of coding data for sepsis, where there are no clear diagnostic criteria, has inherent potential for misclassification bias. Because there is clinical variability in the diagnosis, there is also potential for different diagnostic patterns from different medical specialties which could have a differential impact. For example, if obstetricians were more likely than internal medicine physicians to diagnose patients under their care with sepsis, this could impact the apparent difference in incidence between male and female service members. This study did not evaluate underlying risk factors unless they were coded during the same encounter. There also is potential for confounding between covariates such as race/ethnicity outcomes being attenuated by occupation or branch of service (or vice versa).

The findings of this study suggest that sepsis is an increasing threat to force health protection and is a growing women's health threat as well. Further research is required to evaluate key findings, especially the apparent sex disparity in sepsis rates in the active component which is the inverse of the pattern in the general U.S. population. Such future research should also include adjusted (e.g., age, sex) rates. Studies using clinical and microbiological data would be useful to better understand this growing threat. Additionally, looking into the reasons behind the decline in sepsis diagnoses in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic is important. Changes in health care-seeking behavior may play a role, although how much this would be the case for a life-threatening condition like sepsis is unknown. It is possible that mitigation measures put in place during the pandemic impacted the overall incidence of sepsis by decreasing other infections, especially other respiratory diseases. For example, smaller numbers of recruits, restriction of movement procedures, and enforced social distancing during recruit training may have played a role, and if so could provide valuable information to help structure recruit training in the future in a way that minimizes unnecessary infection risk.

Author affiliations: Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (LCDR Snitchler); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (Dr. Chauhan, Dr. Patel, Dr. Stahlman, CAPT Wells, Ms. Mcquistan).

Disclaimer: The contents of this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the United States Government.

References

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810.

- Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395(10219):200–211.

- Septicemia diagnosed during hospitalizations, active component service members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2012. MSMR. 2013;20(8):10–16.

- Jolley RJ, Quan H, Jetté N, et al. Validation and optimization of an ICD-10-coded case definition for sepsis using administrative health data. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009487.

- Jolley RJ, Sawka KJ, Yergens DW, Quan H, Jetté N, Doig CJ. Validity of administrative data in recording sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):139.

- Kempker JA, Martin GS. The changing epidemiology and definitions of sepsis. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37(2):165–179.

- Williams VF, Oh G, Stahlman S, Shell D. Diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes, active and reserve component service members and dependents, 2008–2018. MSMR. 2020;27(2):8–17.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hospital toolkit for adult sepsis surveillance. Published March 2018. Accessed 16 July 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/pdfs/Sepsis-Surveillance-Toolkit-Mar-2018_508.pdf