Abstract

This study explored rates of death by suicide among active component U.S. Army soldiers during Jan. 1, 2000–June 4, 2021 by birth cohort including Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980), Millennials (1981–1996), and Generation Z (1997–2012). From Jan. 1, 2008 through June 4, 2021, the most likely cluster of suicides, although not statistically significant, was identified between March 2020 and June 2021, which coincided with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Army has observed 55%–82% increases in suicide rates among Millennials, Generation Z, and Generation X compared to 1 year before the pandemic. The largest proportional increase in rates affected the members of Generation X, but the highest rates both before and after the pandemic onset affected those in Generation Z. Discussion of the findings introduces theories that have been used to explain psychological states that may predispose to suicidal behavior and posits ways in which Army leaders and organizations may be able to reduce suicide risk among soldiers. The limitations of the study and possible additional inquiries are described.

What Are the New Findings?

From 2008 through 2021, the most likely cluster of deaths by suicide was identified from March 2020 to June 2021, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the onset of the pandemic, the Army has observed 55%–82% increases in suicide rates among Millennials, Generation Z, and Generation X compared to 1 year before the pandemic.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Assuming a soldier reaches the age range for being eligible for retirement based on at least 20 years of service (between 38 and 62 years), the deaths by suicide between 2000 and 2021 constitute 25,454–82,766 years of life lost to the Army. Findings from the current study suggest the need for additional inquiries to better understand the implications of the pandemic, during which restriction of movement, isolation, and physical distancing necessary to minimize COVID-19 transmission have magnified social health issues among Army soldiers.

Background

The U.S. Army suicide rate has surpassed 20 per 100,000 soldiers since 2008 and reached 30 per 100,000 soldiers in 2018.1 Although the Army suicide rate has been higher in the 17–24 age group in recent years,1 it has not always been the case.2,3 Prior to 2016, Army suicide rates were highest among those aged 25–34;2,3 rates since 2017 have been highest among those 17–24 years.1,4

Because optimal physical, mental, and behavioral health are key to ensure readiness, Army suicide prevention strategies have traditionally focused on individual-level factors (e.g., mental and behavioral health diagnoses, mandatory suicide prevention training). Studies have shown that interventions focused on such factors have been of limited effectiveness in reducing the risk of suicide rates.5 The Army has taken the community-level approach to identify factors associated with suicidal behaviors.6 While common community-level factors emerged from over 10 years of the Army's behavioral health epidemiological consultations6, recommendations accompanying each individual consultation report are not always acted upon or followed through. Suicide shares many community-level risk and protective factors with other harmful behaviors (e.g., intimate partner violence). Shifting the focus from individual harmful outcomes to community-level root causes5, such as social determinants of health7, could allow Army leaders to address suicide and other harmful behaviors using an integrated approach and potentially have a greater impact.

There is a dearth of information on how birth cohorts impact suicidal behavior in the Army, especially during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This study summarized data on the demographic and military characteristics of active component Army soldiers who died by suicide from Jan. 1, 2000 through June 4, 2021. Additionally, a commonly applied method to detect temporal suicide clusters, the scan statistic, was applied to these data in an attempt to identify differences by birth cohort.

Methods

Study Population, Time Frame, and Data Sources

This study was a population-based retrospective analysis of active component Army soldiers who died by suicide from Jan. 1, 2000 through June 4, 2021, as documented by the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES). Monthly population counts of all active component Army soldiers were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System. Demographic data (date of death, date of birth, age, pay grade, rank, sex, racial group, and marital status) for soldiers who died by suicide came from the Defense Civilian Intelligence Personnel System (DCIPS). Soldiers who died by suicide but did not have a date of birth and age at death in DCIPS were excluded from the study (n=6). A total of 2,388 Army soldiers were included in the final analysis.

Descriptive Statistics and Cluster Analyses

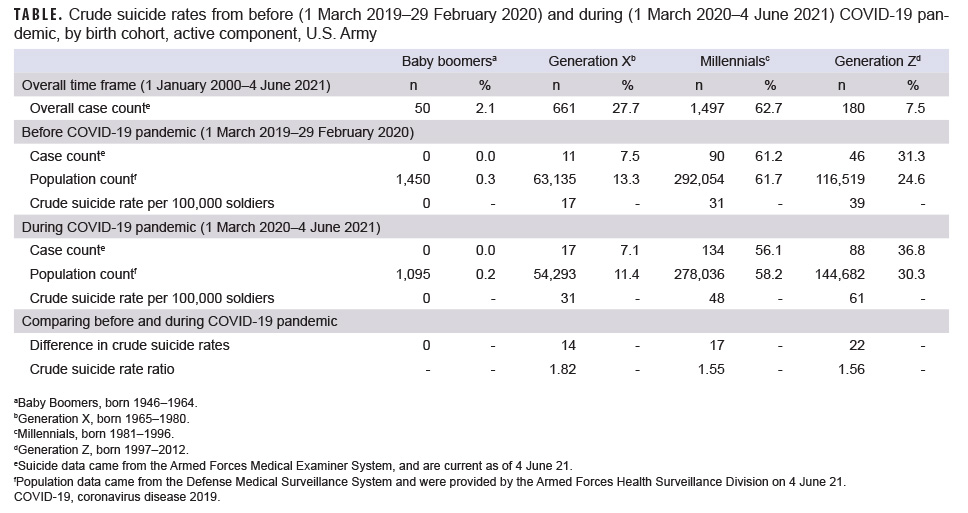

The following 4 successive birth cohorts were included in this analysis: Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980), Millennials (1981–1996), and Generation Z (1997–2012). Demographic characteristics were stratified by birth cohort and differences were assessed using chi-square tests. Crude suicide rates were calculated by birth cohort before (March 1, 2019–Feb. 29, 2020) and during (March 1, 2020–June 4, 2021) the COVID-19 pandemic. These analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.2 (2020, R Core Team).

In general, suicide clusters can be identified by location (spatial) and/or by time (temporal). This study identified temporal-only suicide clusters using a discrete Poisson temporal model available in SaTScan, version 9.6 (2018, M. Kulldorff). The most likely suicide cluster was identified using temporal scan statistics and was calculated for the periods from 2000 through 2021 (with all available data) and 2008 through 2021 (2008 was the first year the adjusted Army suicide rate surpassed the civilian rate8). The discrete scan statistics applied scanning windows over the study period to test whether the number of suicides occurred closer together in time than would normally be expected through random processes. Given the availability of the suicide event date, the time precision for suicide counts was set to day. Suicide counts and population sizes were aggregated by month. The minimum and maximum temporal cluster sizes were set to 1 month and 15 months, respectively. A sensitivity analysis was carried out using the same minimum temporal cluster size and a maximum temporal cluster size extending to half of the study period (software default). A minimum of 2 suicides were required in a cluster. To account for suicide trend, the analysis also incorporated an automatic log-linear adjustment. Statistical significance was determined using a p value generated by a sequential Monte Carlo procedure (software default maximum replications=999).

Results

From Jan. 1, 2000 through June 4, 2021, 2,388 soldiers died by suicide; the majority were male (94%), White (77%), married (56%), junior enlisted (E1–E4; 54%), and Millennials (63%) (data not shown). There were no statistically significant differences in birth cohorts by sex or racial group. However, Generation Z Army members included significantly higher proportions of soldiers who were single and junior enlisted than the 3 other cohorts (data not shown).

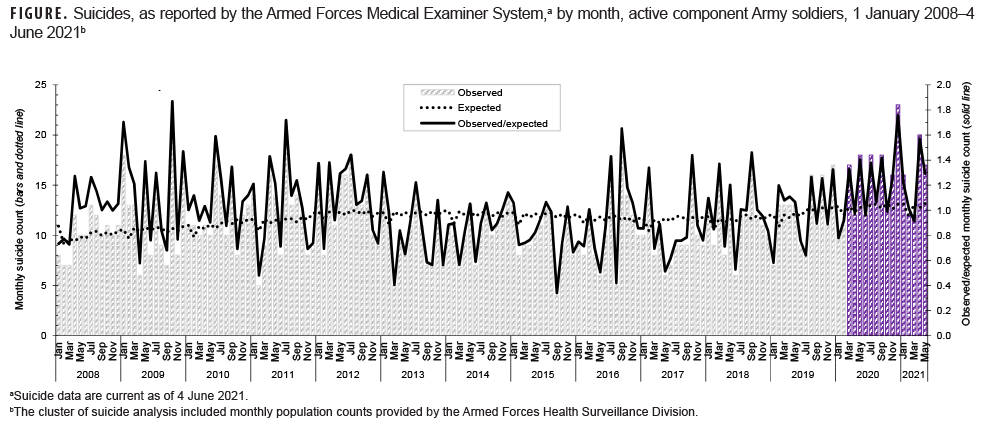

During 2000–2021, a statistically significant cluster of suicides was identified from April 2008 to April 2009, resulting in an Army suicide rate that surpassed the rate for civilians for the first time.9 From Jan. 1, 2008 through June 4, 2021, the most likely cluster of suicides, although not statistically significant, was identified from March 2020 through June 2021, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure). The sensitivity analysis revealed the same result. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Army has observed 55%–82% increases in suicide rates among Millennials, Generation Z, and Generation X compared to 1 year before the pandemic (Table). While Generation Z had the highest absolute increase in the rate of death by suicide (from 39.5 to 60.8 per 100,000) when compared to the year of the pandemic, Generation X soldiers had the highest relative increase in rates during the COVID-19 period rising from 17.4 to 30.8 per 100,000. This represented an 82% increase in the relative rate of death by suicide among Generation X soldiers. Comparatively, there was only a 56% increase in the suicide death rate for Generation Z soldiers (Table).

Editorial Comment

The current study demonstrated pronounced increases in rates of death by suicide from 1 year before the COVID-19 pandemic to the period from 1 March 2020 to 4 June 2021 among soldiers across 3 of the 4 birth cohorts examined. When comparing the 2 time periods, members of Generation Z had the highest absolute increase in suicide rates and Generation X members had the highest relative increase in rates. Assuming a soldier reaches the age range of being eligible for retirement based on at least 20 years of service (between 38 and 62 years), these deaths from 2000 through 2021 constitute 25,454–82,766 years of life lost to the Army. Of note, this is likely an overestimate given that not all soldiers pursue a military career to retirement.

The reasons behind suicidal behavior at various stages in life and potential birth cohort differences may affect soldiers' receptiveness to prevention and intervention efforts. Findings from this study suggest that Generation Z soldiers are at a greater risk for suicide (from 39.5 to 60.8 per 100,000) and Generation X soldiers may have been more impacted by the pandemic (82% increase in suicide rate during pandemic). While Generation Z soldiers born in the digital age could value extrinsic factors (e.g., image, fame) more than intrinsic factors (e.g., self-acceptance, community)10, Generation X soldiers could face deepened despair. A study among Generation Xers in the civilian population demonstrated increased levels of suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, marijuana use, and heavy drinking—compared to previous birth cohorts of the same age.11 This suggests tailoring suicide prevention strategies by birth cohort and having a leader who could provide purpose could have greater impact.

Joiner's Interpersonal Theory of Suicide describes thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capabilities as potential triggers for suicide12 and can be used to explain soldier death by suicide. This theory of suicidal behavior posits that the desire to commit suicide arises as a result of an individual holding 2 specific psychological states in their mind simultaneously for a period of time: "perceived burdensomeness" and "low belongingness".12 Perceived burdensomeness is a feeling that one's existence is a burden to friends, family, society or other social group. A low sense of belongingness corresponds to a sense of alienation or a lack of integration with family, friends, or other social groups.

Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness may be compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of social connectedness due to the pandemic may have intensified feelings of thwarted belongingness, as loneliness has been identified as a public health epidemic in younger populations13 and a risk factor for suicidal ideation.14 With regard to perceived burdensomeness, soldiers place value on their ability to support their unit and accomplish the Army mission. Meaning salience (understanding of one's meaning in life) is important for maintaining and promoting behavioral and social health in times of crisis.15 Trachik et al. found that having leaders who remind soldiers of the purpose of military service amidst stressful experiences can indirectly lower the odds of soldiers having suicidal ideation through unit cohesion that counters thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.16 Moreover, a sense of meaning and purpose is a protective factor under extreme stress17 and having that purpose articulated from a military leader may enhance resilience and reduce risk for suicidal ideation.16,18

With acquired capability, soldiers may have an intensified degree of fearlessness and develop an insensitivity to the pain associated with death by suicide. Previous research demonstrates that service members are more likely to have a greater capability for suicide19, which may be due to exposure to combat violence, death, and pain.20,21 From 2001 through 2021, the most prevalent method of death by suicide was gunshot wound as documented by the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report22,23, DCIPS24,25, and AFMES.24,25 Dempsey et al. found that storing a loaded firearm at home quadrupled the risk of death by suicide among soldiers.26 Hoffmann et al. also found that impulsivity was the strongest predictor of suicide attempt in a sample of 38,507 soldiers.27 Minimizing soldiers' access to firearms/lethal means is an evidenced-based practice in suicide prevention28 and mechanisms to promote lethal means safety29—especially at a time of crisis (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic)—are crucial.

The U. S. Army Public Health Center and other U.S. Government organizations have routinely identified social determinants of health impacting preventable deaths and soldier and family readiness.6 These factors include conditions of military housing30-33, food quality and availability32, quantity and quality of gyms and other recreational areas32, spouse employment opportunities32-34, economic stress and financial literacy32, education and training31,32, family/community support services31,32, racial and ethnic discrimination35,36, health care availability and accessibility14,31,32,37, behavioral health stigma14,31,32, and social isolation.14,32 Focusing on these root causes brings an upstream approach to suicide prevention, where programs, practice, and policies could best synergize and have shown evidence in reducing suicide risk.38

This study has several limitations. Because demographic data came from a single source, there was no additional validation of this information. The study period was based on calendar year and covered various years in service for each birth cohort. Because all 4 birth cohorts of soldiers could not be followed equally for 20 years, the differences by marital status and rank could be an artifact of Generation Z soldiers being in the Army for a shorter period of time. The scan statistics accounted for suicide trend but did not adjust for covariates. The suicide rates from this study were based on preliminary data and were not adjusted for age or sex. Further analyses with adjusted scan statistics and adjusted suicides rates should be considered upon receipt of the annual data in 2021. The study's strengths include over 20 calendar years of suicide records and synchronization of the AFMES data from the latest years with the Army Resilience Directorate to ensure accuracy.

Findings from the current study suggest the need for additional inquiries to better understand the implications of the pandemic, during which restriction of movement, isolation, and physical distancing necessary to minimize COVID-19 transmission have magnified social health issues among Army soldiers.

Author affiliations: Division of Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes Practice, Directorate of Clinical Public Health and Epidemiology, U.S. Army Public Health Center, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD (Dr. Schaughency and Dr. Watkins); Behavioral Health Division, Office of the Surgeon General, Washington, D.C. (LTC Preston).

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge support from the following individuals: Mr. John Wills, Ms. Anita Spiess, Dr. Charles Hoge, Dr. Joseph Abraham, and Dr. John Ambrose.

Human research protections: The Public Health Review Board of the U.S. Army Public Health Center approved this study as Public Health Practice (#21-955) under the Behavioral Health Mission Public Health Surveillance and Monitoring Activities BSHOP Umbrella Project Plan (#16-500).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army Medical Command, the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

References

- Brooks RD, Toussaint M, Corrigan E, Anke K. Surveillance of Suicidal Behavior: U.S. Army Active and Reserve Component Soldiers, Jan.-Dec. 2018. Public Health Report No. S.0049809.1-18. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2020.

- Nweke N, Spiess A, Corrigan E, et al. Surveillance of Suicidal Behavior: Jan. through Dec. 2015. Public Health Report No. S.0008057-15. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2016.

- Brooks RD, Corrigan E, Toussaint M, Pecko J. Surveillance of Suicidal Behavior: Jan. through Dec. 2017. Public Health Report No. S.0049809.1. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2018.

- Brooks RD, Toussaint M. Surveillance of Suicidal Behavior: U.S. Army Active and Reserve Component Soldiers, Jan.–Dec. 2018. Public Health Report No. S.0049809.1-18. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2020.

- Prevention Institute. Back to Our Roots: Catalyzing Community Action for Mental Health and Wellbeing. Prevention Institute; 2017.

- U.S. Army Public Health Center. A Decade of BH EPICONs Lessons Learned. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2021.

- Social Determinants of Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated May 6 2021. Accessed 21 May 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm

- Bachynski KE, Canham-Chervak M, Black SA, Dada EO, Millikan AM, Jones BH. Mental health risk factors for suicides in the US Army, 2007–Inj Prev. 2012;18(6),405–412.

- Watkins EY, Spiess A, Abdul-Rahman I, et al. Adjusting suicide rates in a military population: Methods to determine the appropriate standard population, Am J Public Health. 2018;108(6),769–776.

- Griffith J, Bryan CJ. Suicides in the U.S. Military: Birth Cohort Vulnerability and the All-Volunteer Force. Armed Forces & Society. 2016;42(3):483–500.

- Gaydosh L, Hummer RA, Hargrove TW, et al. The Depths of Despair Among US Adults Entering Midlife. Am JPub Health, 2019;109:774–780.

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University press; 2005.

- Demarinis S. Loneliness at epidemic levels in America. Explore (NY). 2020;16(5):278–279.

- Abdur-Rahman I, Anke K, Beymer M, et al. Assessment of Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes in South Korea, April 2019–March 2020. Technical Report No S.0066218.3-19. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2020.

- Klussman K, Nichols AL, Langer J. Mental health in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal examination of the ameliorating effect of meaning salience. Curr Psychol. 2021; Mar 12:1–8.

- Trachik B, Tucker RP, Ganulin ML, et al. Leader provided purpose: Military leadership behavior and its association with suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285:112722.

- Nock MK, Deming CA, Fullerton CS, et al. Suicide among soldiers: a review of psychosocial risk and protective factors. Psychiatry. 2013;76(2):97–125.

-

Trachik B, Oakey-Frost N, Ganulin ML, et al. Military suicide prevention: The importance of leadership behaviors as an upstream suicide prevention target. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(2):316–324.

-

Assavedo BL, Green BA, Anestis MD. Military personnel compared to multiple suicide attempters: Interpersonal theory of suicide constructs. Death Stud. 2018;42(2):123–129.

- Bryan CJ, Cukrowicz KC, West CL, Morrow CE. Combat experience and the acquired capability for suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(10):1044–1056.

- Bryan CJ, Cukrowicz KC. Associations between types of combat violence and the acquired capability for suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41(2):126–136.

- Defense Health Agency. DoDSER Department of Defense Suicide Event Report: Calendar Year 2018 Annual Report. Defense Health Agency; 2019.

- Department of Defense. Department of Defense Semi-Annual Report to the Committees on Appropriations of the Senate and House of Representatives on Suicide Among Armed Forces Members, March 2021. Department of Defense; 2021.

- Department of Defense. Annual Suicide Report: Calendar Year 2019. Department of Defense; 2020.

- U.S. Army Public Health Center. Methods of Suicide among U.S. Army Soldiers during CY2001–2021 YTD. Memorandum. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2021.

- Dempsey CL, Benedek DM, Zuromski KL, et al. Association of firearm ownership, use, accessibility, and storage practices with suicide risk among US Army soldiers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195383–e195383.

- Hoffmann SN, Taylor CT, Campbell-Sills L, et al. Association between neurocognitive functioning and suicide attempts in U.S. Army Soldiers. J Psychiatr Res. 2020 Nov 7;S0022-3956(20)31071-2.

- Wasserman D, Iosue M, Wuestefeld A, Carli V. Adaptation of evidence-based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry, 2020;19(3):294–306.

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Rogers ML, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Discussing firearm ownership and access as part of suicide risk assessment and prevention: "means safety" versus "means restriction." Arch Suicide Res. 2017;21(2):237–253.

- Johnson L, Jungels AM, McLeod VR. Assessment of Behavioral and Occupational Health within the 25th Infantry Division (25ID), Schofield Barracks, HI, Sept. 21-25, 2015. Technical Report No 14-BB0304-0041704-15. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2017.

- Anke K, Forys-Donahue K, Hall S, et al. Assessment of Behavioral and Psychosocial Health Outcomes within the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), July 2018. Technical Report No S.0058999.3-18. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2019.

-

Anke K, Beymer B, Forys-Donahue K, et al. Assessment of Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes at Fort Wainwright, Alaska, March–Sept. 2019. Technical Report No S.0065762.3-19. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2019.

-

Blue Star Families. 2020 Military Family Lifestyle Survey Comprehensive Report: Executive Summary. Blue Star Families; 2021.

-

Blue Star Families. 2020 Military Family Lifestyle Survey Comprehensive Report: Recommendation. Blue Star Families; 2021.

- Daniel S, Claros Y, Namrow N, et al. Workplace and Equal Opportunity Survey of Active Duty Members: Executive Report. Technical Report OPA-2018-023. Alexandria, VA: Office of People Analytics; 2019.

- Beymer M, Cevis K, Charleston K, et al. People First Task Force Solarium, Assessment of Racism, Extremism, Sexual Harassment and Assault, and Suicide Behavior within Army Culture, West Point, New York, March 2021. Technical Report No S.0079049.3. U.S. Army Public Health Center; 2021.

- Department of Defense. Evaluation of Access to Mental Health Care in the Department of Defense (DODIG-2020-112). Department of Defense; 2020.

- Stone DM, Holland KM, Bartholow B, Crosby AE, Davis S, Wilkins N. Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policies, Programs, and Practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.