Abstract

During 2011–2018, there were 22,729 diagnoses of animal bites among active and reserve component members of the U.S. Armed Forces. Of these, 899 (4.0%) were documented during medical encounters associated with deployments to overseas theaters of operations. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps members were affected by 55.6%, 23.5%, 14.2%, and 6.7% of all animal bites diagnosed in theater, respectively. More than four-fifths of total animal bite cases (82.4%) and bites diagnosed in theater (88.4%) affected enlisted members. The crude overall incidence rate of animal bite diagnoses was 175.7 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) among active component service members between 2011 and 2018. Overall rates were highest among active component service members who worked in law enforcement (462.5 per 100,000 p-yrs) or veterinary occupations (437.8 per 100,000 p-yrs). Among active component service members, the crude annual rate of animal bite diagnoses in 2018 was more than twice that in 2001 (191.4 per 100,000 p-yrs and 85.1 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively). Dog bites accounted for approximately three-quarters (74.8%) of total animal bites during the surveillance period. Only a small proportion of animal bites were associated with documentation of exposure to or post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies. Animal bite avoidance and rabies education should be reinforced before service members travel or deploy to areas where rabies is highly enzootic.

What Are the New Findings?

On average, there were approximately 8 animal bite diagnoses per day among active and reserve component members during 2011–2018. Annual rates of bite diagnoses among active component service members doubled during this period. More than one-third of service members treated for bites in theater received rabies post-exposure prophylaxis. Of 72 bite diagnoses in theater in 2018, only 4 (5.6%) resulted in a confirmed Medical Event Report for rabies post-exposure prophylaxis.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Human animal-bite injuries remain an important public health concern for the U.S. military. Bite injuries are common, and the risk of transmission of rabies, a fatal disease, makes it essential that medical care providers, especially those in rabies enzootic areas, be knowledgeable about when and how to provide pre-exposure rabies immunizations and post-exposure prophylaxis whenever indicated.

Background

Human animal-bite injuries are relatively common worldwide and represent a significant public health problem because of the associated risk of rabies virus exposure, skin infection, and tissue damage. Most animal bites produce only minor injuries; however, depending on the size and type of biting animal, wounds can range from minimal to life-threatening.1 Risk of infectious complications increases if animal bites are left untreated or if treatment is delayed.1

Despite the potential public health consequences of human animal-bites, such injuries have not been routinely tracked at the local or regional level in the U.S.2,3 Retrospective reviews of hospital records have estimated that between 2 and 5 million animal bites occur annually in North America; these injuries accounted for about 1% of emergency department visits and an estimated 10,000 inpatient admissions annually.3–5

Rabies is the most important public health concern associated with human animal-bite injuries. This disease is caused by infection with viruses in the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus, the most common of which is Rabies lyssavirus.6 Rabies virus is generally transmitted through exposure to the saliva of an infected animal, most commonly through bite wounds, open cuts in skin, or mucous membranes.7 In mammals, including humans, rabies virus spreads via peripheral nerves to the central nervous system.8 Viral replication and shedding of rabies viruses occurs in highly innervated areas such as the salivary glands.8 Infection of the brain causes acute, progressive inflammation leading to difficulty swallowing, hydrophobia, neurologic deficits, abnormal behavior, paralysis, seizures, coma, and ultimately death.9

In the U.S., wild animals are the most likely source of human exposure to rabies.9 Rabies surveillance in the U.S. has identified bats (with multiple rabies virus variants in multiple species), raccoons, skunks, and foxes as the 4 major animal reservoirs.10,11 During 2017, 49 states reported 4,423 rabid animals and 2 human rabies cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12 Wildlife accounted for 91.3% of rabies cases reported in the U.S. in 2017; bats were the most frequently reported rabid wildlife species (32.4% of all animal cases), followed by raccoons (28.8%), skunks (21.2%), and foxes (7.1%).12

Currently, there is no known effective treatment for symptomatic rabies, and progression to death is rapid once symptoms appear.7 Human rabies survival is exceptionally rare and, when it does occur, is often associated with severe neurologic sequelae.13 However, if exposure to rabies is identified early, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), which includes immediate wound care and the administration of human rabies immune globulin (HRIG) and rabies vaccine, is highly effective in preventing progression of the infection and clinical manifestations.3,14,15 Individuals who have been previously vaccinated or are receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for rabies should receive only rabies vaccine and any necessary wound care. Administration of HRIG is unnecessary in such cases because the vaccination booster stimulates an effective anamnestic antibody response.14

Service members are at risk for animal bites and rabies exposures in the U.S. and during deployment to areas of the world where canine rabies is enzootic, including Africa, Asia, and parts of Central and South America.16,17 Risk of exposure to rabies is higher for service members in certain military occupations such as veterinary service personnel, working dog handlers, personnel who have animal control duties, certain laboratory workers who work with rabies-suspect samples, and special operations personnel.7,9,18–20 Department of Defense (DOD) instruction mandates personnel in these occupations receive rabies PrEP18–20; however, exposure to a potentially rabid animal still requires administration of rabies PEP.19 PrEP is also considered for service members with longer-term assignments to regions where rabies is enzootic.18–20

In 2011, the MSMR summarized the numbers and types (but not rates) of animal bite diagnoses and rabies PEP among active and reserve component service members during 2001–2010.21 The current analysis updates and expands on this earlier work by describing the incidence rates of animal bite diagnoses among active component service members between 2001 and 2018 and examining the number of reportable medical event (RME) records of "confirmed" rabies PEP for all animal bite cases in 2018.

Methods

The surveillance period for the update of incidence rates was 1 Jan. 2001 to 31 Dec. 2018. For the more detailed analyses of demographic and military characteristics of bite victims, the surveillance period was limited to 2011–2018. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active or reserve component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. Diagnoses indicative of animal bites were ascertained from Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) electronic records of all medical encounters of individuals who received care in fixed (i.e., not deployed or at sea) medical facilities of the Military Health System (MHS) or civilian facilities in the purchased care system. Records of health care encounters of deployed service members are maintained in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS), which is incorporated into the DMSS.

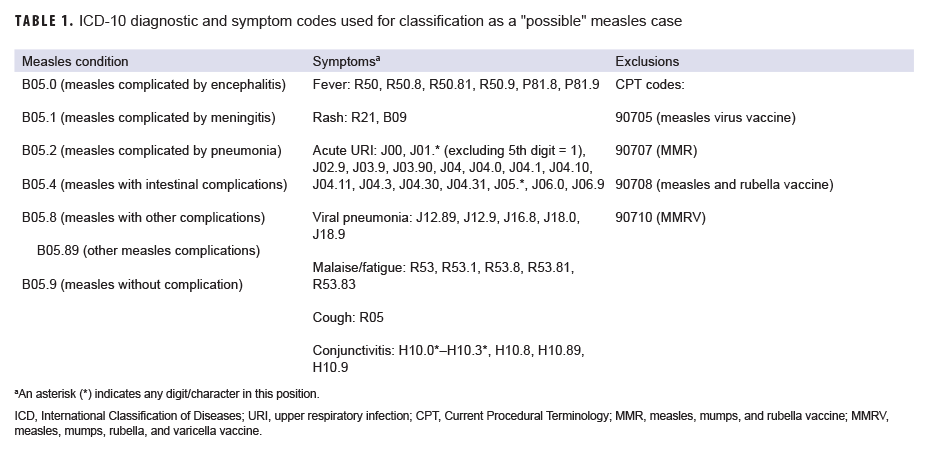

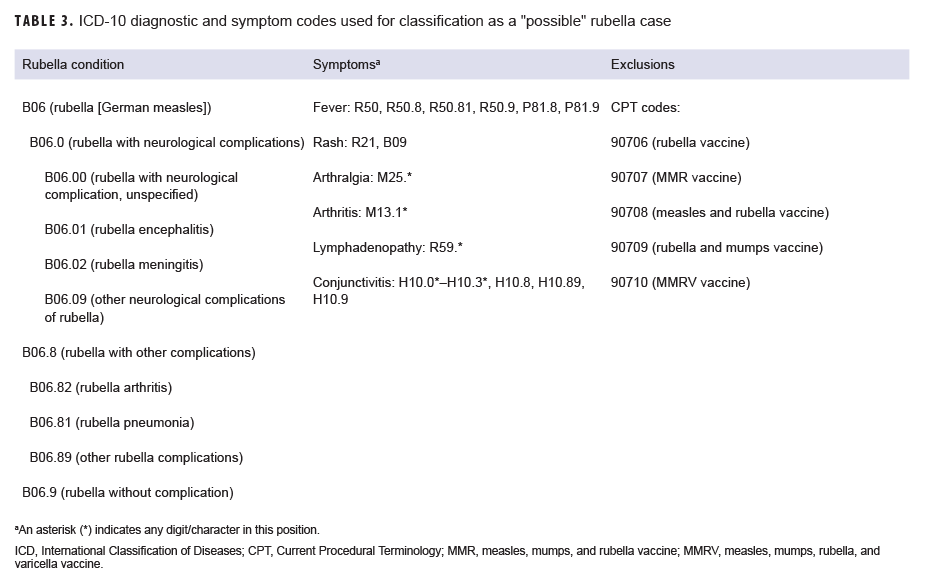

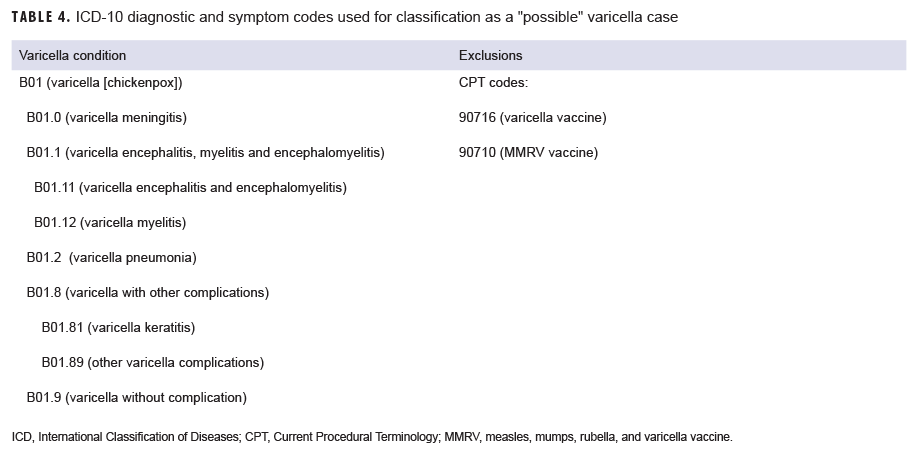

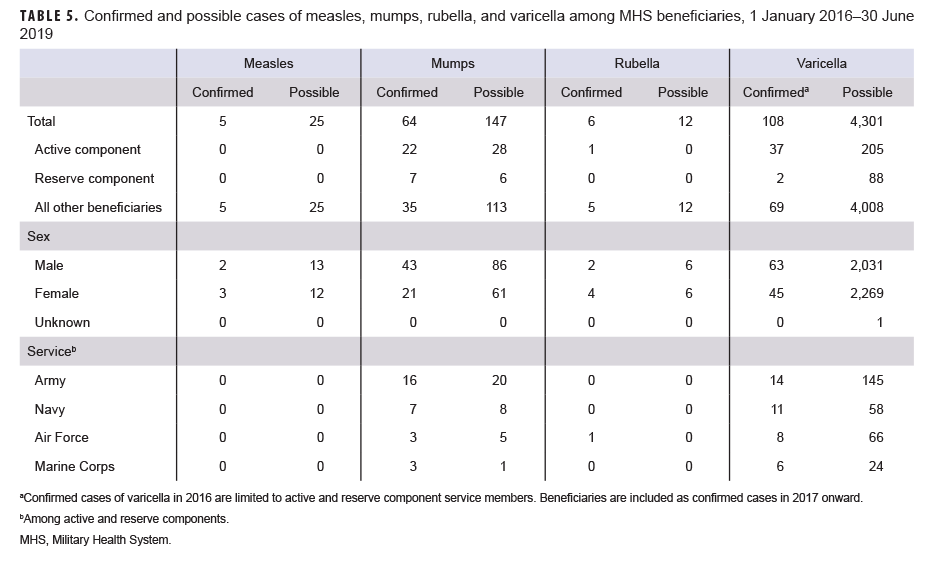

For the current analysis, a case was defined as an individual with an inpatient or outpatient International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9] or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10] diagnosis code of "animal bite" in any diagnostic position (Table 1). In order to prevent the counting of follow-up encounters for single animal bite episodes as new cases, each service member could be counted as a case only once per calendar year. In each calendar year, animal bite diagnoses associated with deployments to overseas theaters of operations (TMDS, "in theater") were prioritized over those from non-deployed settings (DMSS, "outside of theater"). Incidence rates of animal bite diagnoses were calculated for active component service members between 2001 and 2018. Incidence rates were not calculated for reserve/guard members because the DMSS does not contain activated service time for reserve/guard personnel.

For all service members identified as animal bite cases during 2011–2018, the number of such cases whose records contained diagnostic codes for "exposure to rabies" (ICD-9: V01.5; ICD-10: Z20.3) was determined. In addition, for all bite cases, the number who received rabies PEP as shown in immunization records (i.e., rabies vaccine, HRIG, and unspecified immune globulin) within 90 days of animal bite diagnoses were ascertained. The codes used to identify instances of rabies vaccine (CVX codes) and immunoglobulin administration are presented in Table 2.22

RME records of "confirmed" rabies PEP were also identified for all animal bite cases. It is DOD policy that administration of PEP against rabies must be reported electronically through military health channels for surveillance purposes.23 However, because the reporting policy for RMEs of rabies PEP took effect in 2017, the current analysis was limited to those events reported among members of the active and reserve components during 2018.

The new electronic health record for the MHS, MHS GENESIS, was implemented at several military treatment facilities during 2017. Medical data from sites that are using MHS GENESIS are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounters for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities during 2017–2018 were not included in this analysis.

Results

During the 8-year surveillance period, there were 22,729 diagnoses of animal bites among U.S. service members in the active and reserve components; on average, there were approximately 8 animal bite diagnoses per day throughout the period. Of all animal bite diagnoses among active and reserve component service members, 899 (4.0%) were documented during medical encounters in theater (Table 3a).

Male service members accounted for over three-quarters (77.9%) of animal bite diagnoses overall and 83.8% of those diagnosed in theater. More than one-half (55.9%) of all animal bites and almost two-thirds (66.3%) of those diagnosed in theater affected 20–29 year old service members. Non-Hispanic white service members were affected by almost three-quarters of all animal bites—both overall (71.1%) and in theater (72.2%)—that were documented on electronic health care records during medical encounters (Table 3a).

Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps members were affected by 55.6%, 23.5%, 14.2%, and 6.7% of all animal bites that were diagnosed in theater. Compared to their in-theater counterparts, Army and Navy members in non-deployed settings accounted for relatively lower percentages (47.3% and 17.1%, respectively) and Air Force and Marine Corps members had relatively higher percentages (25.9% and 9.7%, respectively) of cases. More than four-fifths of total animal bite cases (82.4%) and bites diagnosed in theater (88.4%) affected enlisted members (Table 3a).

Among active and reserve component service members deployed in theater, those in combat-specific (n=268; 29.8%) or repair/engineering occupations (n=221; 24.6%) accounted for the most animal bite diagnoses; together, service members in these occupational groups accounted for more than one-half (54.4%) of animal bites diagnosed in theater (Table 3a). Among service members outside of theater, those in repair/engineering (n=5,492; 25.2%) and communication/intelligence (n=4,753; 21.8%) occupations accounted for the greatest percentages of animal bite diagnoses. These occupational groups accounted for 46.9% of all animal bite diagnoses outside of theater. Veterinarians and other veterinary medicine workers (e.g., animal care specialists, animal health technicians) accounted for 26 (2.9%) animal bite cases in theater and 511 (2.3%) cases outside of theater during the surveillance period.

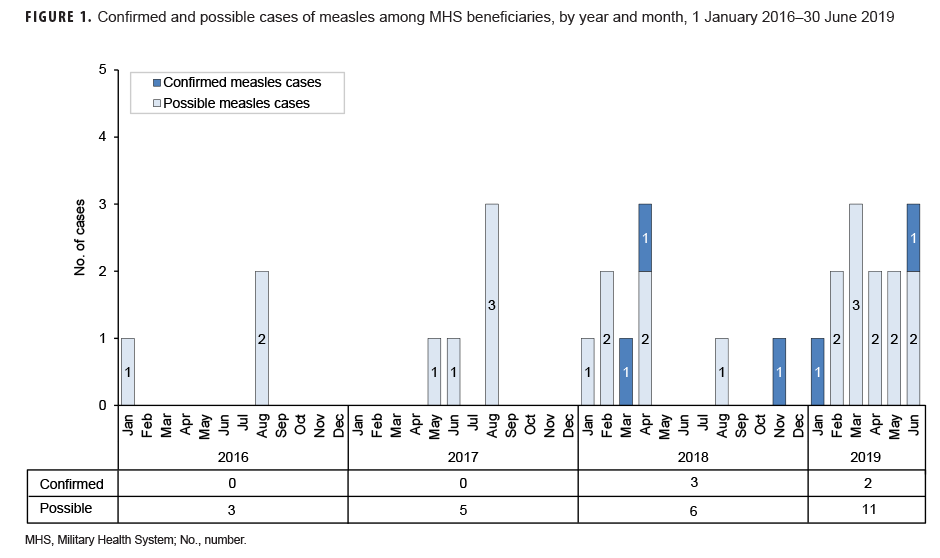

The crude overall incidence rate of animal bite diagnoses was 175.7 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) among active component service members between 2011 and 2018 (Table 3b). Compared to their respective counterparts, active component service members who were female (241.9 per 100,000 p-yrs), 20–29 years old (190.4 per 100,000 p-yrs), members of the Army (204.2 per 100,000 p-yrs), and senior enlisted (199.9 per 100,000 p-yrs) tended to have higher overall rates of animal bite diagnoses. Across military occupations, overall rates of animal bite diagnoses were highest among active component service members working in law enforcement (462.5 per 100,000 p-yrs) and those in veterinary occupations (437.8 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 3b). Among service members in the active component, the crude annual rate of animal bite diagnoses in 2018 was more than twice that in 2001 (191.4 per 100,000 p-yrs and 85.1 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Figure 1).

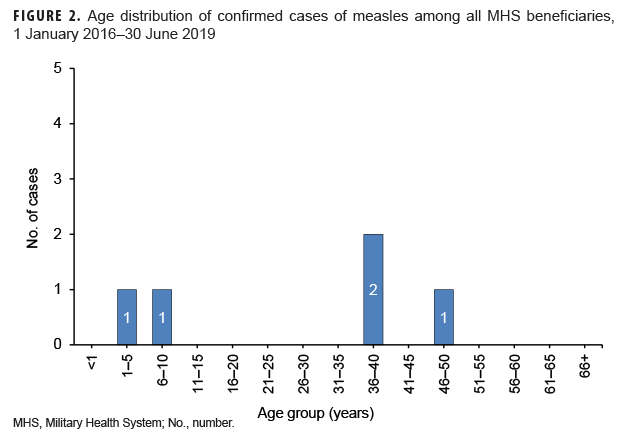

Among active and reserve component service members, dog bites accounted for the majority of animal bites diagnosed outside of (75.4%) and in theater (58.2%) (Figure 2). Almost 1 in 4 (23.7%) of the animal bites diagnosed in theater were classified as having been attributed to "other animals" including cats, horses, cows, other hoof stock, pigs, and raccoons. Of note, rat bites accounted for 3.4% of animal bite cases in theater and less than 1% of cases outside of theater.

Of all animal bite diagnoses recorded outside of theater (n=21,830) during 2011–2018, 658 (3.0%) were associated with a diagnosis of exposure to rabies during a medical encounter within 90 days after the animal bite diagnosis (Table 4). Almost three-quarters (n=490; 74.5%) of exposures to rabies diagnoses were documented within 1 week after the animal bite diagnosis. Fifty-nine (9.0%) of the 658 exposures to rabies diagnoses were documented 31–90 days after the animal bite diagnosis. Approximately one-eighth (12.6%; n=2,745) of the animal bite diagnoses recorded outside of theater were associated with rabies vaccination that was administered within 90 days after the diagnosis of the bite; less than 5% (3.8%; n=830) of the animal bites were associated with HRIG administration within 90 days after the animal bite diagnosis (Table 4). Almost seven-eighths (87.1%) of the animal bite cases who were reportedly vaccinated and 89.2% of the cases who received HRIG received the respective PEP within 1 week after the bite diagnoses.

Of all animal bite cases diagnosed in theater, 28 (3.1%) were documented as exposure to rabies; more than three-eighths (39.3%) of the exposure to rabies diagnoses were documented within 1 week after the animal bite diagnosis and one-quarter (25.0%) were documented 31–90 days after the animal bite diagnosis (Table 4). Of the 899 in-theater animal bite cases, 316 (35.2%) reportedly received rabies vaccine and 139 (15.5%) received HRIG within 90 days of the bite diagnoses. The vast majority of PEP associated with animal bite diagnoses recorded in theater were documented during medical encounters within 1 week after the respective bite diagnoses.

In 2018, of the 3,031 animal bite diagnoses recorded outside of theater, less than 5% (n=117; 3.9%) resulted in a confirmed RME for rabies PEP (Table 5). Of the 72 animal bite diagnoses recorded in theater in 2018, 4 (5.6%) resulted in a confirmed RME for rabies PEP (Table 5).

Editorial Comment

Human animal-bite injuries remain an important public health concern for the U.S. military.17,24,25 There were an average of 8 animal bite diagnoses per day among active and reserve component service members between 2011 and 2018. During this period, approximately 1 of every 25 animal bites overall were diagnosed in theater. Crude annual rates of animal bite diagnoses more than doubled from 2001 to 2018.

While this report documents about 55 clinically diagnosed animal bite cases among U.S. active and reserve component service members each week during 2011–2018, it undoubtedly significantly underestimates the actual numbers of animal bites. For example, most injuries from animal bites are minor; in such cases, service members are unlikely to seek medical care. However, even minor animal bite injuries can have serious consequences—particularly bites inflicted by wild animals (including bats, foxes, skunks, and raccoons), feral cats and dogs, and pets with unknown rabies vaccination statuses.3

In the current analysis, dog bites accounted for the largest proportion of animal bites of service members overall. Among service members in the U.S., dog bites are most likely inflicted by pets or military working dogs.26,27 Such dogs are generally known to the bite victim and have almost always been vaccinated against rabies.27 As such, it is not surprising that a small proportion of all service members who were treated for animal bites outside of theater received rabies PEP (i.e., rabies vaccination, HRIG). In contrast, more than one-third of service members who were treated for animal bites in theater reportedly received rabies PEP. It is likely that instances of diagnoses of "exposure to rabies" that were associated with HRIG administration but no rabies vaccine were the result of termination of PEP when the biting animal was deemed to be rabies free.

When considering the percentage of animal bite cases in 2018 that were associated with confirmed RMEs for rabies PEP, it is important to note that guidelines specify that cases must meet 1 or more of 3 exposure criteria. These criteria include a bite, scratch, or other contact situation in which saliva or central nervous system tissue of a rabid or potentially rabid animal could have entered an open wound or come into contact with a mucous membrane (i.e., eye, mouth, or nose); inadvertent contact with a bat or situation in which bat contact cannot be ruled out (e.g., finding a bat in a room with a sleeping person); or receipt of donated organ tissue from suspected or known human cases of rabies.23 Guidelines also specify that an RME for PEP should not be reported in cases where PEP was initiated but subsequently deemed unnecessary because a full rabies exposure risk assessment found that none of the criteria were met.23 Among the animal bite cases diagnosed outside of theater, the discordance between the number of cases who reportedly received PEP based on immunization data and the number of confirmed RMEs for PEP suggests that information on a subset of PEP administrations was not captured, accurately classified, and/or submitted through the Disease Reporting System internet (DRSi). Similar gaps in RME surveillance have been noted for other diseases.28 Findings of the current analysis highlight the importance of training DRSi reporters at military treatment facilities on the critical reporting elements and the exposure criteria that inform final case classification.

Given the potentially lethal consequences of rabies, all service members should be educated regarding the importance of avoiding wild and stray animals (particularly feral dogs and cats) and protecting against and seeking medical care for animal bites. Animal bite avoidance and rabies education should be reinforced before service members travel or deploy to areas where rabies is highly enzootic; service members at high risk should be considered for pre-exposure rabies vaccination.19,29 Medical care providers at all levels—and particularly those serving in areas where rabies is enzootic—should communicate with veterinary providers as needed in assessing risk and determining need for PEP as well as be knowledgeable and capable of providing pre-exposure rabies immunizations and PEP whenever indicated (Table 6).

The range of destinations for U.S. military deployments, including humanitarian assistance, peacekeeping, and partnership-building missions, has broadened in recent years, making the potential for rabies exposure more variable and difficult to predict.17,29 The increased likelihood of rabies exposure when conducting operations in areas where rabies is enzootic requires accurate risk assessment, ongoing risk communication, robust surveillance, and strong leadership engagement to prevent service member exposure to potentially rabid animals.17,30

References

- Hargrove JR, Freer L. Wild animal attacks and injuries. In: Bledsoe GH, Manyak MJ, Townes, DA, eds. Expedition and Wilderness Medicine. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009:27–28.

- Gilchrist J, Sacks JJ, White D, Kresnow MJ. Dog bites: still a problem? Inj Prev. 2008;14(5):296–301.

- Lyu C, Jewell MP, Piron J, et al. Burden of bites by dogs and other animals in Los Angeles County, California, 2009–2011. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(6):800–808.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2): e10–52

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonfatal dog bite-related injuries treated in hospital emergency departments—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(26):605–610.

- Begeman L, GeurtsvanKessel C, Finke S, et al. Comparative pathogenesis of rabies in bats and carnivores, and implications for spillover to humans. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(4):e147–e159.

- Manning SE, Rupprecht CE, Fishbein D, et al. Human rabies prevention—United States, 2008: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-3):1–28.

- Warrell MJ, Warrell DA. Rabies and other lyssavirus diseases. Lancet. 2004;363(9413):959–969.

- Brown CM, Slavinski S, Ettestad P, Sidwa TJ, Sorhage FE. Compendium of animal rabies prevention and control, 2016. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;248(5):505–517.

- Birhane MG, Cleaton JM, Monroe BP, et al. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2015. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;250(10):1117–1130.

- Feder HM Jr, Petersen BW, Robertson KL, Rupprecht CE. Rabies: still a uniformly fatal disease? Historical occurrence, epidemiological trends, and paradigm shifts. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012;14(4):408–422.

- Ma X, Monroe BP, Cleaton JM, et al. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2017. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253(12):1555–1568. 13. Jackson AC. Human rabies: a 2016 update. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2016;18(11):38.

- Rupprecht CE, Briggs D, Brown CM, et al. Use of a reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-2);1–9.

- Defense Health Agency, Immunization Health Care Division. Information paper. Rabies disease and rabies vaccine. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Fact-Sheets/2019/07/03/Rabies-Diseaseand-Rabies-Vaccine. Published 3 July 2019. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019.

- Wallace RM, Petersen BW, Shlim DR. Rabies. In: Brunette GW, Nemhauser JB, eds. CDC Yellow Book 2020: Health Information for International Travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2019:316.

- Johnson LA, Lennon RP. Expeditionary force health protection for global health engagement: lessons learned from Continuing Promise 2017. Mil Med. 2018;183(5–6): e166–e173.

- Headquarters. Departments of the Army, Navy, and the Air Force. Army Regulation 40-905, SECNAVINST 6401.1B, AFI 48-131. Medical Services: Veterinary Health Services. 29 Aug. 2006.

- Woodson J. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Memorandum: Human Rabies Prevention During and After Deployment. Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 14 Nov. 2011.

- Headquarters, Departments of the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Coast Guard. Army Regulation 40-562, BUMEDINST 6230.15B, AFI 48–110_IP, CG COMDTINST M6230.4G. Medical Services: Immunizations and Chemoprophylaxis for the Prevention of Infectious Diseases. 7 Oct. 2013.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Animal bites, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001–2010. MSMR. 2011;18(9)12–15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization information systems (IIS). IIS: HL7 standard code set mapping CVX to vaccine groups. https://www2a.cdc.gov/vaccines/iis/iisstandards/vaccines.asp?rpt=vg#vg. Accessed 9 Sept. 2019.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Armed Forces Reportable Medical Events. Guidelines and Case Definitions, 2017. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2017/07/17/Armed-Forces-Reportable-Medical-Events-Guidelines. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019.

- Cooper ED, Debboun M. The relevance of rabies to today’s military. US Army Med Dep J. 2012;Jul-Sep:4–11.

- Garges EC, Taylor KM, Pacha LA. Select public health and communicable disease lessons learned during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. US Army Med Dep J. 2016;(2-16):161–166.

- Royal J, Taylor CL. Planning and operational considerations for units utilizing military working dogs. J Spec Oper Med. 2009;9(1):5–9.

- Schermann H, Eiges N, Sabag A, et al. Estimation of dog-bit risk and related morbidity among personnel working with military dogs. J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17(3):51–54.

- Ambrose JF, Kebisek J, Gibson KJ, White DW, O’Donnell FL. Commentary: Gaps in reportable medical event surveillance across the Department of the Army and recommended training tools to improve surveillance practices. MSMR. 2019;26(8):17–21.

- Moe CD, Keiser PB. Should U.S. troops routinely get rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis? Mil Med. 2014;179(7):702–703.

- Mease LE, Whitman S, Lawrence RE. Brief report: Increased number of possible rabies exposures among U.S. health care beneficiaries treated in military clinics in southern Germany in 2016. MSMR. 2018;25(11):18–20.