Abstract

The validity of military hepatitis C virus (HCV) surveillance data is uncertain due to the potential for misclassification introduced when using administrative databases for surveillance purposes. The objectives of this study were to assess the validity of the surveillance case definition used by the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) for HCV, the over and underestimation of cases from surveillance data, and the true burden of HCV disease in the U.S. military. This was a validation study of all potential HCV cases in the active component U.S. military from calendar year 2019 obtained using several different data sources: 1) outpatient, inpatient, and reportable medical event (RME) records in the Defense Medical Surveillance System, 2) Health Level 7 (HL7) laboratory data obtained from the Navy Marine Corps Public Health Center, and 3) chart review of the electronic medical records of all potential HCV cases, to include those from privately-sourced care. The sensitivity of the MSMR case definition was 83.6% and the positive predictive value (PPV) was 60.0%. This study suggests that the U.S. military should have confidence that the previous estimates derived using the MSMR surveillance case definition were moderately close to the true burden of incident chronic HCV infection (the true incidence of chronic disease being about 27% lower), but these reports likely dramatically overestimate the incidence of acute HCV. Since HCV was selected as an RME to guide public health action, it is most suitable to invest public health efforts in strengthening the use of confirmed RMEs as the surveillance case definition.

What are the new findings?

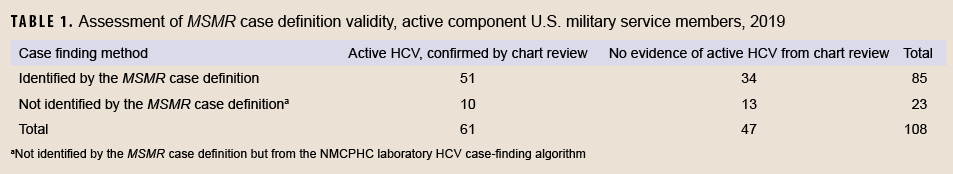

A total of 61 active component U.S. military service members were confirmed as cases of active HCV infection in 2019, which was 28% lower than the number of individuals who met the MSMR case definition for HCV in the same year (n=85).

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

This study suggests that the U.S. military should have confidence that the previous estimates derived using the MSMR surveillance case definition were moderately close to the true burden of incident chronic HCV infection, but these reports likely dramatically overestimate the incidence of acute HCV.

Background

Untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection not only poses risks to the health and readiness of those military service members who have already been infected, but it also poses a risk of transmission to previously uninfected service members when utilizing the walking blood bank where whole blood transfusions are given during emergency situations in combat.1 U.S. military force health protection posture to counter these risks is informed by accurate and timely surveillance reporting. However, the validity of the HCV surveillance data presented in previous issues of the MSMR 2 is uncertain due to the potential for misclassification introduced when using administrative databases for surveillance purposes. This uncertainty arises because of the complexity and difficulty in extracting the necessary data to accurately and completely identify confirmed cases from administrative data according to criteria established by either the Department of Defense (DOD) reportable medical event (RME) surveillance3 or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notifiable diseases.4,5

Specifically, national HCV guidelines state that “A test to detect HCV viremia is therefore necessary to confirm active HCV infection and guide clinical management, including initiation of HCV treatment.”6 However, ascertainment and use of laboratory data from the military health system (MHS) electronic medical records (EMR) systems to confirm HCV poses challenges for health surveillance. Laboratory results may be entered as free text fields and are not standardized across facilities or over time. Extractions from laboratory databases are computationally and labor intensive, and the potential cases that are identified still require validation to ensure they are correctly classified, as noted in a previous MSMR report.7 Further difficulty arises in that approximately one-fifth of medical encounters for active component service members in 2021 occurred in privately sourced care outside of MHS direct care facilities (Dr. S. Stahlman, written communication, 2 September 2022). For those patients, the data available for surveillance purposes are often restricted to documentation required for medical billing, including diagnostic codes from outpatient and inpatient visits and prescriptions for HCV medications. Records from privately sourced care may be uploaded into the EMR’s Health Artifact and Imaging Management Solution (HAIMS); however, even when available these records are only available in portable document format (PDF), making the data they contain even more difficult to extract for surveillance purposes.

For these reasons, the HCV surveillance case definition used by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD) has excluded laboratory data. The current MSMR HCV surveillance case definition includes any of the following: 1) one reportable medical event of a confirmed case of HCV, 2) one hospitalization for HCV in any diagnostic position, or 3) two outpatient visits for HCV within 90 days of each other in any diagnostic position.8 Nevertheless, the aforementioned data limitations contribute to uncertainty about the validity of this HCV surveillance case definition, hindering the application of surveillance findings towards public health action. For example, HCV estimates from a previous report published in the MSMR 2 were compared to estimates obtained from other unpublished military data sources, and discrepancies were observed. The objective of this study was therefore to assess the validity of the MSMR’s surveillance case definition for HCV, the over and under-estimation of cases from surveillance data, and the true burden of HCV disease in the U.S. military. This information will also be used to update the surveillance case definition for HCV used in MSMR reports.

Methods

This was a validation study of all potential HCV cases in the active component U.S. military from calendar year 2019 obtained using the following data sources: 1) the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) using the MSMR surveillance case definition for HCV, 2) Health Level 7 (HL7) laboratory data obtained from the Navy Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC) case-finding algorithm designed to identify all tests which were HCV RNA positive, and 3) chart review for all potential HCV cases of all outpatient and inpatient records in the EMR, to include those from privately-sourced care in HAIMS. This project was reviewed and approved by the Uniformed Services University Institutional Review Board. Data from the DMSS included HCV type (acute, chronic), dates of diagnoses, demographics (race, gender, service, age at diagnosis), report type (inpatient, outpatient, RME), number of visits by HCV type, and HCV diagnostic position for each visit. Laboratory surveillance data obtained from the NMCPHC case-finding algorithm included laboratory test type, dates, and results, as described previously.7

Cases were validated by the two physician authors through chart review of military electronic medical records, with an emphasis on laboratory confirmation; reason for testing and type of HCV (acute or chronic) were also assessed. Cases were assessed as valid if they met the CDC case definition for notifiable diseases as a confirmed case of chronic or acute HCV.

The CDC and DOD case definitions for confirmatory evidence of HCV both include a positive nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA, which includes qualitative, quantitative, or genotype testing. Cases may also be confirmed (uncommonly) by either a positive HCV antigen test or anti-HCV test conversion (from negative to positive within a 12-month period).3-5 Active cases were defined as those with confirmed acute or chronic HCV.

The PPV and sensitivity of the MSMR case definition were assessed using the definitions established by CDC for the evaluation of surveillance systems.9 The PPV was defined as the proportion of individuals with confirmed HCV disease among the total number identified by the case finding method (e.g., the MSMR case definition). The sensitivity was defined as the proportion of individuals identified by the case finding method (e.g., the MSMR case definition) among the total number of confirmed cases identified by either the MSMR case definition or the laboratory algorithm. PPV and sensitivity were assessed overall and according to the type of record (or combination of record types), position of the HCV diagnosis code, and number of HCV encounters. Correction factors were obtained from the assessment of confirmed cases identified using the MSMR case definition and false negative individuals identified only by the laboratory case-finding algorithm. These correction factors were then applied to the total population of cases identified using the MSMR surveillance case definition to obtain weighted estimates of the true burden of HCV.10

Results

There were 85 unique individuals from 2019 who met the MSMR case definition for HCV, all of whom were selected for chart review (Table 1). Of these, 8 were classified as both acute and chronic HCV cases, as the MSMR case definition allows for these both to be counted if the acute diagnosis comes first.8 If tabulated as in previous reports,2 this would have resulted in 83 possible chronic and 10 possible acute cases, for a total of 93 possible cases (data not shown). All 85 individuals who met the MSMR case definition were asymptomatic, although two were discovered as part of a workup for elevated liver function tests. However, for these 2 individuals, their total bilirubin remained <3 and alanine transaminase (ALT) < 100; therefore, none of the individuals were found to have confirmed acute HCV. Thus, a total of 51 confirmed chronic cases and no confirmed acute cases were identified among those individuals who met the MSMR case definition in 2019 (Table 1). All 34 unique individuals who were identified by the MSMR case definition but not confirmed from chart review had a positive HCV antibody test and a negative RNA confirmatory test, indicating cured infection or possibly a false positive antibody test. Of the 51 confirmed cases identified by the MSMR case definition, 49 (96%) were provided direct care in MHS facilities, the other 2 received privately sourced care. Twenty-eight of the 51 confirmed cases were immediately discharged from military service: 17 who were identified in basic training, 4 at retirement, and 7 during discharge for illegal substance use. Of the 19 confirmed HCV cases which were not reported as RMEs, 5 were found as part of a substance use workup, 4 as part of a blood donation in Army or Air Force basic training, 2 during other blood donation screening, 4 at time of retirement or medical discharge from service, 2 as part of a screening for sexually transmitted infections, and two had no relevant characteristics (data not shown).

There were also 51 individuals from the same year who were found to be possible HCV cases based on NMCPHC laboratory case-finding algorithm; all of these were chart-reviewed as well. Thirty-eight (75%) of these individuals were found to have confirmed HCV, and all were chronic HCV. Of the 38 individuals with confirmed chronic HCV identified by the laboratory case-finding algorithm, 28 were also identified using the MSMR case definition (data not shown).

The total number of individuals with confirmed HCV among the active component U.S. military in 2019 was thus 61, of which 10 (16%) were not identified by the MSMR case definition; these data are summarized in Table 1. The sensitivity of the MSMR case definition was 83.6% (51 of 61 total confirmed individuals were identified by the MSMR case definition) and the PPV was 60.0% (51 of 85 individuals meeting the MSMR case definition were confirmed). In contrast, the NMCPHC laboratory case-finding algorithm resulted in a sensitivity of 62.3% (38 of 61 confirmed individuals were identified by the laboratory algorithm) and a PPV of 74.5% (38 of 51 individuals identified by the laboratory algorithm were confirmed).

The MSMR case correction factor was 60.0% (95% CI: 49-70%), and the MSMR non-case correction factor was 43.5% (95% CI: 23-66%). These are the proportions of confirmed cases from the total number of potential HCV cases which were and were not identified by the MSMR’s HCV case definition, respectively. After applying the correction factors, the ratio of individuals with confirmed HCV (n=61) to those meeting the MSMR case definition (n=85) was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.60-0.84), meaning that the number of unique individuals with incident HCV in the active component military was 28% lower than that suggested by the number identified using the MSMR case definition. Equivalently, the MSMR case definition resulted in 39% overreporting of individuals with active HCV compared to the true estimate of confirmed cases.

Since previous MSMR reports presented HCV surveillance data separately for acute and chronic HCV rather than active infection,2 this analysis estimated the amount of misclassification for each type. Since none of the acute HCV cases were confirmed, the MSMR case definition used in previous reports overestimated acute HCV incidence by 100%. In contrast, the number of confirmed cases of chronic HCV (n=61) was 27% lower than that identified by the MSMR case definition (n=83).

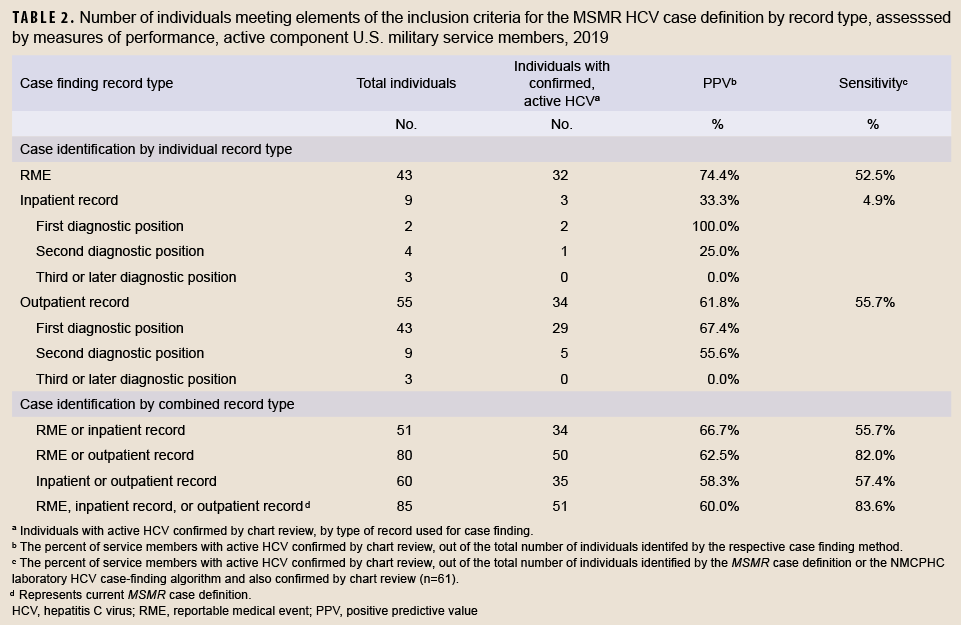

The distribution of records by inclusion criteria for the MSMR HCV case definition are shown in Table 2. All record types were seen to have significant limitations in validity of diagnosis, with RMEs having the highest PPV (74.4%) for confirmed cases and inpatient records having the lowest (33.3%). Various combinations of record types resulted in increased sensitivity, but reduced PPV compared to RME records. For example, of the 80 individuals who had an RME or an outpatient HCV record, 50 were confirmed, with a PPV of 62.5% and a sensitivity of 82.0%. Nevertheless, this was only slightly different than the existing MSMR case definition (PPV=60.0%, sensitivity=83.6%), and would result in similar overcounting of HCV if used for surveillance in the absence of chart review (80 individuals with RME or outpatient records compared to 61 individuals with confirmed HCV). In contrast, outpatient and RME records alone slightly undercounted the true incidence of confirmed HCV, while inpatient records dramatically undercounted this incidence. Of those 67 who only had 6 visits or less with an HCV diagnosis, 34 (51%) had confirmed HCV. Of the 18 who had seven or more visits, 16 (89%) had confirmed HCV (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

The number of individuals with confirmed active HCV infection in the active component U.S. military was 61 in 2019, which was 28% lower than the number of unique individuals who met the MSMR case definition for HCV the same year (n=85). This is because only 60% of cases identified using the MSMR case definition were found to be confirmed, and 16% of confirmed cases were not identified by the MSMR case definition. However, the degree of misclassification was heterogeneous by HCV type (acute or chronic). None of the 10 cases which the MSMR case definition identified as acute HCV were found to be confirmed as acute, suggesting that all of these cases may also have been misclassified in previous reports.2 Furthermore, only 61 cases of chronic HCV were confirmed in 2019, which was 27% lower than the number of chronic cases identified by the MSMR case definition (n=83), suggesting that the true incidence of chronic HCV in previous years was of a similarly lower magnitude. The sensitivity and PPV varied according to the combinations of record types and increases in sensitivity resulted in decreases in PPV (and vice versa). Estimates of HCV incidence in the U.S. military should account for this overreporting of both chronic and acute cases. Since no confirmed acute cases were identified, MSMR surveillance should only perform surveillance on chronic HCV or simply refer to it as HCV (unspecified)—with a note that all or nearly all are chronic cases.

The NMCPHC laboratory surveillance and MSMR surveillance case finding algorithms demonstrated similar results and conclusions, and both have significant limitations in sensitivity and PPV. However, current informatics capabilities make the laboratory-based surveillance time-consuming and difficult, and therefore is likely impractical in most situations. This study revealed that the likely reason some cases were not reported during the previous lab-based study7 was that they were excluded from the analysis as they did not remain on active duty past 1 January 2020; i.e., they were discharged from basic training, retired, or were discharged due to illegal substance use. However, some may have also been missed by the lab algorithm since many may have been ordered in settings known to have limitations when used for surveillance purposes, such as privately-sourced care, blood donation, shipboard facilities, and in-theater facilities.11 Nevertheless, in accordance with CDC’s HCV surveillance guidelines, DOD should establish a method to receive hepatitis C laboratory data and ensure it is entered into its RME system to improve the accuracy and completeness of HCV reporting, preferably through an automated electronic laboratory reporting system.12

The main limitation of this report is the absence of a true “gold standard” for HCV case status. The chart review adds further clarification on classification of chronic and acute infection; however, the potential for referrals to privately sourced care facilities likely contribute to incomplete review of all electronic medical records. Thus, reliance on chart review for confirmation of infection may also be vulnerable to persistent misclassification and underestimation of the true burden of HCV disease.

This study suggests that the U.S. military should have confidence that the previous estimates derived using the MSMR surveillance case definition were moderately close to the true burden of incident chronic HCV infection (the true incidence being about 27% lower), but these reports likely dramatically overestimate acute HCV. For surveillance purposes, it is most important to maintain consistency in disease reporting standards to identify trends and factors which can be used to evaluate public health programs and guide policies and public health action. Since no single or combination of report types resulted in high sensitivity or PPV, several of the case definitions studied could be reasonably chosen as a surveillance case definition. Since HCV was selected as an RME to guide public health action, it is most suitable to invest public health efforts in strengthening the use of confirmed RMEs as the surveillance case definition. RMEs had the highest PPV of any of the case report types studied here, an intermediate level of sensitivity compared to other case report types, and a similar magnitude of reported cases (n=43) compared to the true disease burden (n=61).

Furthermore, public health personnel are the ideal group to improve disease reporting and to ensure all laboratory confirmed cases meet the case definition, as this group supports and inputs the RME data. Finally, HCV RMEs are most similar to the notifiable conditions used by the states and CDC, making this report type the most directly comparable to other civilian HCV surveillance reports.13

Nevertheless, any case definition selected for surveillance purposes in future reports will need to acknowledge the likelihood of disease under or overreporting. For example, if confirmed RMEs are used as the surveillance case definition, reports should acknowledge in the limitations section that the true disease burden is likely to be on the order of 42% higher. Public health personnel can use the information in this report to improve both surveillance data accuracy and completeness. In addition to the automated laboratory reporting described above, efforts at communicating with health care personnel providing substance use treatment, blood donations, or discharge physicals may improve HCV reporting. Future reports should also acknowledge the difficulty in comparing with previous reports, which used the surveillance case definition which included RME, outpatient, and inpatient report types. Specifically, they should note in the limitations section that instead of underestimating the true HCV incidence, these prior reports overestimated the true disease burden by 39%. Future studies should assess the impact of any efforts at improving surveillance data accuracy and/or completeness, such as implementation of a laboratory reporting system, implementation of a new EMR (i.e., MHS Genesis), and other temporal trends.

Author affiliations

Department of Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD (Dr. Mancuso, Dr. Legg); Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center, Portsmouth, VA (Mr. Seliga); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Stahlman).

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, assertions, opinions, or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or of the U.S. Government.

References

- Ballard T, Rohrbeck P, Kania M, Johnson LA. Transfusion-transmissible infections among U.S. military recipients of emergently transfused blood products, June 2006-December 2012. MSMR. Nov 2014;21(11):2-6.

- Stahlman S, Williams VF, Hunt DJ, Kwon PO. Viral hepatitis C, active component, U.S. military service members and beneficiaries, 2008-2016. MSMR. May 2017;24(5):12-17.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Armed Forces Reportable Medical Events: Guidelines and Case Definitions. Defense Health Agency. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Pub

lications/2020/01/01/Armed-Forces-Reportable-Medical-Events-Guidelines. Updated 1 Jan 2020. Accessed 15 May 2021.

- Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS): Hepatitis C, Acute, 2020 Case Definition. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-c-acute-2020/. Updated 16 March 2021. Accessed 15 March 2022.

- Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS): Hepatitis C, Chronic, 2020 Case Definition. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-c-chronic-2020/. Updated 16 April 2021. Accessed 15 March 2022.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C: HCV Testing and Linkage to Care. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/evaluate/testing-and-linkage. Updated 29 September 2021. Accessed 14 March 2022.

- Legg M, Seliga N, Mahaney H, Gleeson T, Mancuso JD. Diagnosis of hepatitis C infection and cascade of care in the active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2020. MSMR. Feb 1, 2022;29(2):2-7.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Surveillance Case Definitions: Hepatitis C Case Definition. Department of Defense. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Health-Readi

ness/AFHSD/Epidemiology-and-Analysis/Surveillance-Case-Definitions. Updated November 2018. Accessed 4 July 2022.

- German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, et al. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep. Jul 27 2001;50(RR-13):1-35; quiz CE1-7.

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, Third Edition. Wiley-Interscience; 2013.

- Poitras B. Description of the MHS Health Level 7 Microbiology Laboratory Database for Public Health Surveillance. Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1073987.pdf. Updated 18 April 2019. Accessed 16 Sept 2022.

- Division of Viral Hepatitis. Hepatitis C Surveillance Guidance. National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/surveillanceguidance/HepatitisC.htm. Updated 21 Sept 2021. Accessed 2 September 2022.

- Ryerson AB, Schillie S, Barker LK, Kupronis BA, Wester C. Vital Signs: Newly Reported Acute and Chronic Hepatitis C Cases - United States, 2009-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Apr 10 2020;69(14):399-404. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6914a2