Background

Menstrual suppression allows for the control or complete suppression of menstrual periods through hormonal contraceptive methods. In addition to preventing pregnancy, suppression can alleviate medical conditions and symptoms associated with menstruation such as iron deficiency anemia,1 eliminate logistical hygiene-related challenges, and improve quality of life. Suppression methods include short-acting methods such as oral contraceptive pills, transdermal patches, vaginal rings, and injections or long-acting intrauterine devices. While research, including a recent Cochrane review,2 has found menstrual suppression methods to be efficacious and safe, these methods remain underutilized.3

Given the growing number of women serving in the military,4,5 it is increasingly important to ensure that service women are given the information and resources to manage menstrual-related sanitary practices and hygiene challenges to improve both personal health and force readiness.6,7 Multiple studies have found that most female service members were interested in suppressing menstruation during field training and deployments.8-11 However, relatively few female service members were aware of available methods of menstrual suppression9 while even fewer were offered the option of menstrual suppression during pre-deployment counseling.7,11,12 Despite this interest in menstrual suppression, reports of prevalence of menstrual suppression across the services are not available.13 This report describes the prevalence of menstrual suppression at two time points by demographic and military characteristics among female service members enrolled in the Millennium Cohort Study.

Methods

The Millennium Cohort Study is the largest and longest running prospective study of U.S. service members with over 250,000 enrolled participants representing all branches and components.14,15 The 2007–2008 and 2011–2013 surveys (hereafter called 2008 and 2013 surveys, respectively) included questions on menstrual suppression in the female-only section assessing reproductive health. Demographic and military characteristics were obtained from the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) using data closest to the survey date. Time-varying characteristics, including age, marital status, pay grade, military occupation, service component, and deployment status, represent the status as of the date of survey completion. Deployment dates in and out of theater from the Contingency Tracking System (CTS) were used to identify those who had deployed in the year before survey completion. Marital status and education level were obtained from surveys and backfilled with DMDC data closest to survey date if missing.

This analysis was restricted to female service members in the active component, aged 18–50 at the time of survey completion, who completed survey questions regarding menstrual suppression for the first time on the 2008 or 2013 survey. Additionally, those who reported hysterectomy, menopause, pregnancy, and/or breastfeeding as the reason for no menstrual cycle in the preceding 12 months were excluded. Menstrual suppression was defined as responding “no” to the binary question “Have you had at least one menstrual period in the past 12 months” and identifying “contraception or hormone therapy” as the reason from 6 possible options for having no menstrual period. Point prevalence estimates were calculated overall and by demographic and military characteristics at each time point. Two-sided chi-square test statistics were calculated to identify significant differences (a=.05) between the prevalence observed at the 2008 and 2013 time points.

Results

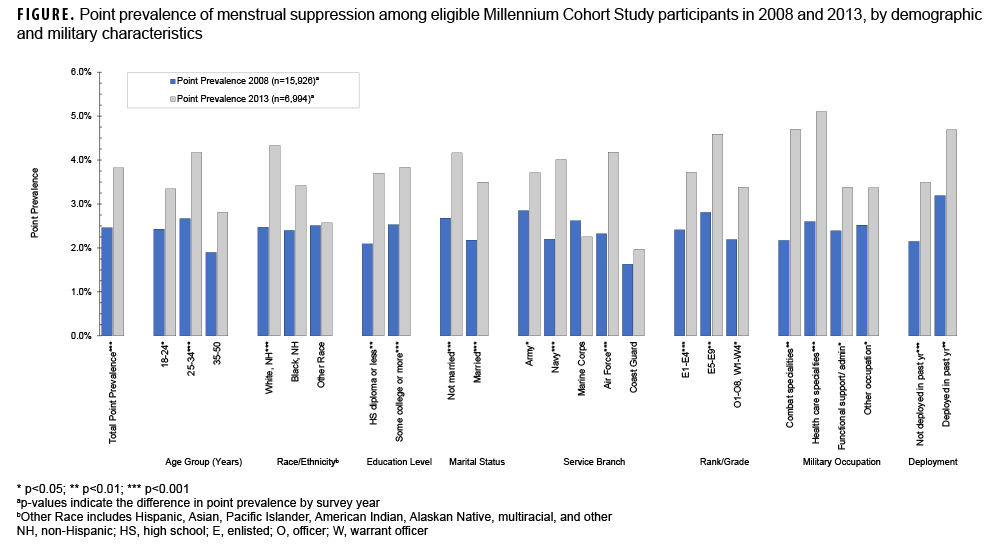

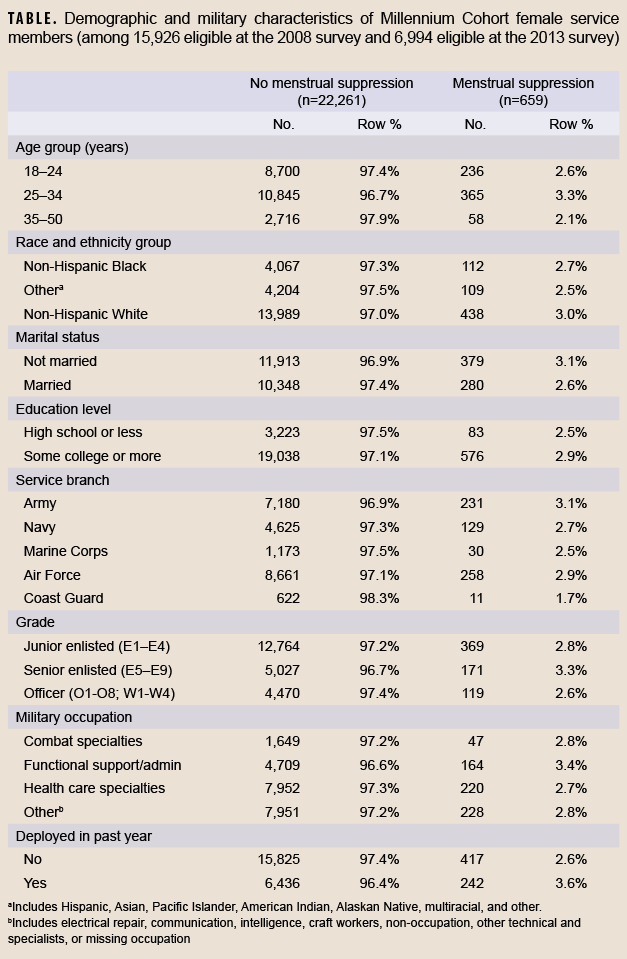

A total of 22,920 enrolled female service members were eligible for this analysis (Table), with 15,926 eligible at the 2008 survey and 6,994 eligible at the 2013 survey. There was a significant increase in point prevalence of menstrual suppression when comparing the 2008 and 2013 prevalence (2.5% versus 3.8% respectively, p<.001). As illustrated in the Figure, point prevalence of menstrual suppression was significantly higher (p<.05) on the 2013 survey than the 2008 survey by female service members who were 18–24, 25–34 years old, or of non-Hispanic White race and ethnicity. The prevalence of menstrual suppression increased among all levels of education and marital status when comparing the 2008 and 2013 cohorts.

Female Army, Navy, and Air Force members reported a significant increase in menstrual suppression while no significant change was seen among those in the Marine Corps or Coast Guard. Higher prevalence of menstrual suppression was reported in 2013 compared to 2008, regardless of rank or military occupation. Prevalences of menstrual suppression increased among those who deployed within the past year and among those who did not deploy. The highest prevalences of menstrual suppression in 2013 were among female service members who deployed in the past year (4.7%) or had an occupation in health care or combat specialties (5.1% and 4.7%, respectively).

Editorial Comment

These findings suggest that menstrual suppression increased among U.S. female service members from 2008 through 2013. While this increase occurred across demographic and military categories, there was unequal adoption of menstrual suppression among certain subgroups of female service members.

At the time of this report, only 2 other studies have reported prevalence of menstrual suppression among female service members. Powell-Dunford reported that 7% (±4%, 95% CI) of a convenience sample of female Army members (n=154) at Walter Reed Medical Center suppressed their menstrual cycle ever during field training or deployment.10 Another study reported that 21% of female Army members indicated continuous oral contraceptive use during deployment.16Comparisons between these findings and those of the current study should be undertaken with caution as this 2011 paper surveyed a sample of deployed Army personnel (n=500 Active Duty, National Guard or Reserve personnel) and defined menstrual suppression as 3 continuous months of oral contraceptive use.16

Access to menstrual suppression during deployment not only ensures menstrual control, but can also decrease the risk of iron deficiency anemia and reduce the need for evacuation out of theatre due to heavy menstrual bleeding or pregnancy.7While CENTCOM MOD 14 (Modification 14 to USCENTCOM Individual Protection and Individual/Unit Deployment Policy)17 mandates pre-deployment appointments to address medical issues as well as a 180-day supply of maintenance medication, this policy does not specifically apply to menstrual management or contraception use.7 Discussion of menstrual suppression methods at pre-deployment appointments may also be too late as many methods involve irregular bleeding in the first few months of adoption.7,18Recently established programs to address this knowledge gap include full-service walk-in contraceptive clinics,19 dissemination of information on contraceptive use for reproductive and menstrual suppression purposes through the “Decide + Be Ready” mobile app, and the addition of questions pertaining to contraceptive use and counseling on the annual Periodic Health Assessment.20 Equipping female service members with the tools to manage their health care needs improves their health, readiness, and their ability to contribute to overall unit readiness.

A notable limitation of this analysis is that survey-derived estimates may not be reflective of the overall menstrual suppression prevalence of all female service members. In the absence of a validated measure for menstrual suppression, the prevalence estimates in this study are conservative and may exclude those who opted for shorter menstrual suppression cycles or started menstrual suppression less than 12 months before survey completion. Female service members who use menstrual suppression solely during deployment may not have been captured in this study as deployment periods can vary, with many lasting less than 12 months. However, the large sample size and inclusion of all service branches and both deployed and non-deployed personnel facilitated a unique and more representative look at menstrual suppression. The consistent characterization of menstrual suppression across Millennium Cohort longitudinal surveys, with another round of data collection expected in 2023, allows for the assessment of long-term trends of menstrual suppression.

Author affiliations

Leidos, Inc., San Diego, CA (Yunnuo Zhu, Claire Kolaja, Rayna Matsuno); Deployment Health Research Department, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Yunnuo Zhu, Claire Kolaja, Rayna Matsuno, Rudolph Rull); CSP #505: Millennium Cohort Study, VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, Seattle, WA (Nicole Stamas).

Disclaimer

Dr. Rull is an employee of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of his official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. Report No. 22-07 was supported by the Military Operational Medicine Research Program under work unit no. 60002. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol, number NHRC.2000.0007.

References

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Iron deficiency anemia, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2002-2011, July 2012. MSMR. 2012;19(7):17-21.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014; Issue 7. Art. No.: CD004695.

- Nappi RE, Kaunitz AM, Bitzer J. Extended regimen combined oral contraception: A review of evolving concepts and acceptance by women and clinicians. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;21(2):106–115.

- Amara, J. Military women and the force of the future. Defense Peace Econ. 2021;31(1), 1–3.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Military Personnel: DOD is Expanding Combat Service Opportunities for Women but Should Monitor Long-Term Integration Progress. Report to Congressional Committees. 2015;GAO-15-589.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Female Active-Duty Personnel: Guidance and Plans Needed for Recruitment and Retention Efforts. Report to Congressional Committees. 2020; GAO-20-61.

- Keyser EA, Westerfield K, Eagan S, et al. Making the case for menstrual suppression for military women. Mil Med. 2020:185(7-8):e923–e925.

- Trego LL, Jordan PJ. Military women's attitudes toward menstruation and menstrual suppression in relation to the deployed environment: Development and testing of the MWATMS-9 (short form). Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(4):287-93.

- Ricker EA, Goforth CW, Barrett AS, et al. Female Military officers report a desire for menstrual suppression during military training. Mil Med. 2021;186(Suppl 1):775–783.

- Powell-Dunford NC, Deuster PA, Claybaugh JR, et al. Attitudes and knowledge about continuous oral contraceptive pill use in military women. Mil Med. 2003;168(11):922–928.

- Eagan SM. Menstrual suppression for military women: Barriers to care in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(1):72–76.

- Nielsen PE, Murphy CS, Schulz J, et al. Female soldiers' gynecologic healthcare in Operation Iraqi Freedom: A survey of camps with echelon three facilities. Mil Med. 2009;174(11):1172–1176.

- Phillips AK, Lynn AB. Scoping review on menstrual suppression among U.S. military service members. Mil Med. 2021; Epub ahead of print.

- Gray GC, Chesbrough KB, Ryan MA, et al. The Millennium Cohort Study: A 21-year prospective cohort study of 140,000 military personnel. Mil Med. 2002;167(6):483–488.

- Ryan MA, Smith TC, Smith B, et al. Millennium Cohort: Enrollment begins a 21-year contribution to understanding the impact of military service. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(2):181-191.

- Powell-Dunford NC, Cuda AS, Moore JL, et al. Menstrual suppression for combat operations: advantages of oral contraceptive pills. Women’s Health Issues. 2011;21(1):86–91.

- USCENTCOM 031815Z OCT 19 MOD FOURTEEN TO USCENTCOM INDIVIDUAL PROTECTION AND INDIVIDUAL-UNIT DEPLOYMENT POLICY. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2019/11/19/USCENTCOM-SG-MOD-14-Final. Accessed 16 August 2022.

- Hillard PA. Menstrual suppression: Current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014; 6:631–637.

- Adams KL. Operation PINC: Process improvement for non-delayed contraception. Mil Med. 2017;182(11): e1864-e1868.

- Witkop CT, Torre DM, Maggio LA. Decide + be ready: A contraceptive decision-making mobile application for servicewomen. Mil Med. 2021;186(11–12):300–304.