Background

Of the approximately 3,000 known snake species in the world, about 20% (i.e., 600 species) are venomous.1 Snakebite envenomation (SBE) occurs when venom is injected into a human or animal via a snake's fangs, or much less frequently, via spitting venom into a victim's eye or open wound. Not all snakebites result in envenomation; an estimated 25% to 50% of snakebites are "dry bites" in which an insufficient amount of venom is injected to cause clinical symptoms.2,3 Clinical effects of snake envenomation can range from mild local effects (e.g., superficial puncture wounds, pain and swelling) to more severe complications including permanent disability and death.3

SBEs are a significant public health issue especially in the tropical and subtropical areas of Africa, Asia, and Latin America.4 In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified SBE as a neglected tropical disease. WHO estimates between 1.8-2.7 million SBEs occur annually, resulting in an estimated 81,410 to 137,880 deaths.5 Each year in the U.S., there are an estimated 5,000-10,000& SBEs and fewer than 10 associated deaths.6

Although rare, SBEs are an occupational hazard for military members worldwide. The recent published literature on SBE in military members is sparse. During contingency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, self-reported incidence of snakebite in U.S. troops was 4.9 snakebites per 10,000 person-months.7 A recent review of snakebites treated between 2015-2017 by the French military health service in overseas locations identified only two soldiers (1 French, 1 Dutch) treated for SBE in Mali, both of whom were treated with antivenom and recovered fully.8 A 2018 summary of snakebites in UK personnel focused on Europe and Africa and reported on an envenomation in a UK service member bitten by a horned viper in Croatia. This summary also highlighted that the majority of SBE cases treated by military medical providers occurred among local civilians.9 The only death attributed to SBE in a U.S. service member that was reported in the lay press occurred in 2015 in Kenya.10

No comprehensive summary of all medically diagnosed SBEs in U.S. service members worldwide has been published. This analysis summarizes the incidence of SBE in active and reserve component service members identified through review of administrative medical data. This analysis also provides a breakdown of SBEs by demographic and military characteristics including the country and combatant command in which the SBEs were treated.

Methods

The surveillance period was from 1 Jan. 2016 through 31 Dec. 2020. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active or reserve component of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. The Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) was searched for all inpatient, outpatient and/ or theater medical encounters that contained any of the ICD-10 codes falling under the parent code T63.0 ("Toxic effect of snake venom") in any diagnostic position. Because ICD-9 diagnoses still appear in the theater medical encounter data, service members could also qualify as a case if they had a diagnosis of ICD-9: 989.5 ("Toxic effect of venom") or E905.0 ("Venomous snakes and lizards causing poisoning and toxic reactions"). The patient assessment field was reviewed for these ICD-9 coded records to determine whether the injury was caused by a snake, and only the records for injuries that were caused by snakes were retained. A service member could be counted as an incident case once per year. The location of the SBE was determined by mapping the treating facility for the SBE to a specific country and combatant command.

Results

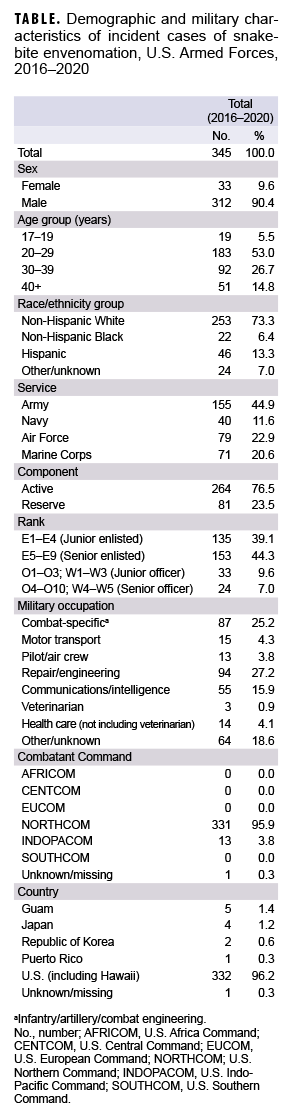

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 345 SBEs were diagnosed in U.S. service members. Approximately 90% of cases were among male service members and about 45% occurred in soldiers. More than three-quarters of SBEs were diagnosed among active component service members (Table). The majority of cases occurred in service members in the 20-29 year old age group. Service members in the repair/engineering and combat-specific occupational groups were the most frequently affected by SBEs and constituted over half of all SBEs during the period (Table).

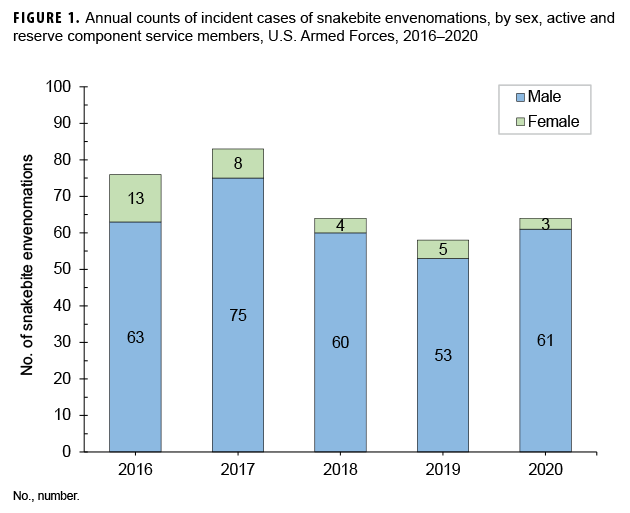

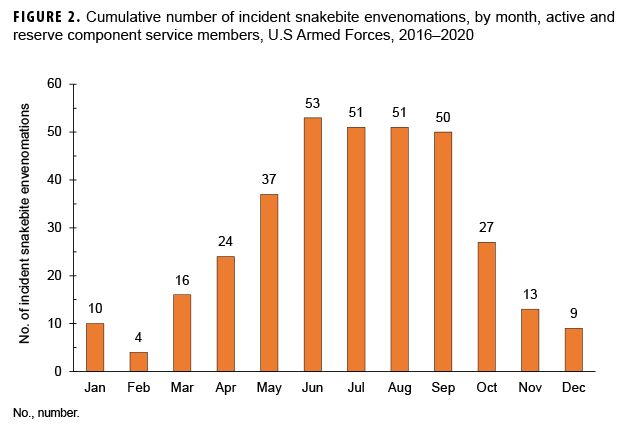

The annual numbers of SBEs were at their highest in 2017 (n=83); this peak represented a 9.2% increase in SBEs over the prior year. Total SBEs declined by 22.6% in 2018 and a further 9.4% in 2019; 2019 had the lowest number of incident cases of SBE during the surveillance period (n=58). Incident cases increased by 10.3% in 2020 (n=64) which was the same level as 2018 (Figure 1). Overall, 59.4% (n=205) of the cases occurred between the months of June and September (Figure 2).

Most SBE cases (96.2%) were diagnosed in the U.S.; consequently, almost 96% of cases occurred in the U.S. Northern Command (Table). Cases diagnosed in Hawaii are attributed to the U.S. IndoPacific Command. Counts of cases by specific location were 1 in Puerto Rico, 330 in the U.S. (excluding Hawaii), 5 in Guam, 4 in Japan, 2 in Korea, 2 in Hawaii, and 1 with an unknown location.

Editorial Comments

This analysis demonstrates that the vast majority of medically diagnosed SBEs in U.S. service members during 2016-2020 occurred in the U.S. In accordance with the findings of a recent report on the epidemiology of snakebites in the U.S., male service members were disproportionately affected by SBEs.6

This analysis is subject to the same limitations as any analysis of administrative medical data. Only SBEs that were diagnosed by a medical provider and entered into a service member's electronic medical record could be included in this analysis. An SBE could also be missed due to miscoding or because medical care for an SBE was not documented in the medical record.

In the U.S., service member SBEs occur more frequently during warm weather months. Preventive measures for avoiding SBE include precautions such as avoiding snakes in the wild, wearing long pants or boots when working or walking outdoors, and wearing gloves when handling brush or reaching into areas that might house snakes. Anyone bitten by a snake should seek medical attention as soon as possible.11,12

Although this analysis demonstrates that the majority of service members' SBEs occur in the U.S., appropriate precautions should be taken to avoid SBE during deployment outside of the U.S. Planning for deployment should include education in the medically important snake species and the appropriate medical management of snakebites specific to deployment location. In 2020, the Joint Trauma System published a Clinical Practice Guideline for Global Snake Envenomation Management (CPG ID:81) which provides a comprehensive guide to snakebite management by combatant command.12

References

- Venemous snakes distribution and species risk categories. World Health Organization. Accessed 08 May 2021. https://apps.who.int/bloodproducts/snakeantivenoms/database/

- Pucca MB, Knudsen C, S Oliveira I, et al. Current Knowledge on Snake Dry Bites. Toxins (Basel). 2020;12(11):668.

- Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guideline: Global Snake Envenomation Management. Accessed 08 May 2021. https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Global_Snake_Envenomation_Management_30_Jun_2020_ID81.pdf

- Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, Gunawardena NK, Pathmeswaran A, Premaratna R, et al. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5(11):e218.

- World Health Organization. Snake bite envenomation. 2019. World Health Organization. Accessed April 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/snakebite-envenoming

- Greene SC, Folt J, Wyatt K, Brandehoff NP. Epidemiology of fatal snakebites in the United States 1989-2018. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Aug 29:S0735-6757(20)30777-30784.

- Shiau DT, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, et al. Selfreported incidence of snake, spider, and scorpion encounters among deployed U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2007;172(10):1099-1102.

- Bomba A, Favaro P, Haus R, et al. Review of Scorpion Stings and Snakebites Treated by the French Military Health Service During Overseas Operations Between 2015 and 2017. Wilderness Environ Med. 2020;31(2):174-180.

- Wilkins D, Burns DS, Wilson D, Warrell DA, Lamb LEM. Snakebites in Africa and Europe: a military perspective and update for contemporary operations. J R Army Med Corps. 2018 Sep;164(5):370-379.

- Montgomery, Nancy. Soldier died of venomous snake bite, autopsy confirms. Stars and Stripes. March 15, 2015. Accessed May 08, 2021. https://www.stripes.com/news/soldier-died-of-venomous-snake-bite-autopsy-confirms-1.334382

- Torpy JM, Schwartz LA, Golub RM. JAMA patient page. Snakebite. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1657.