Abstract

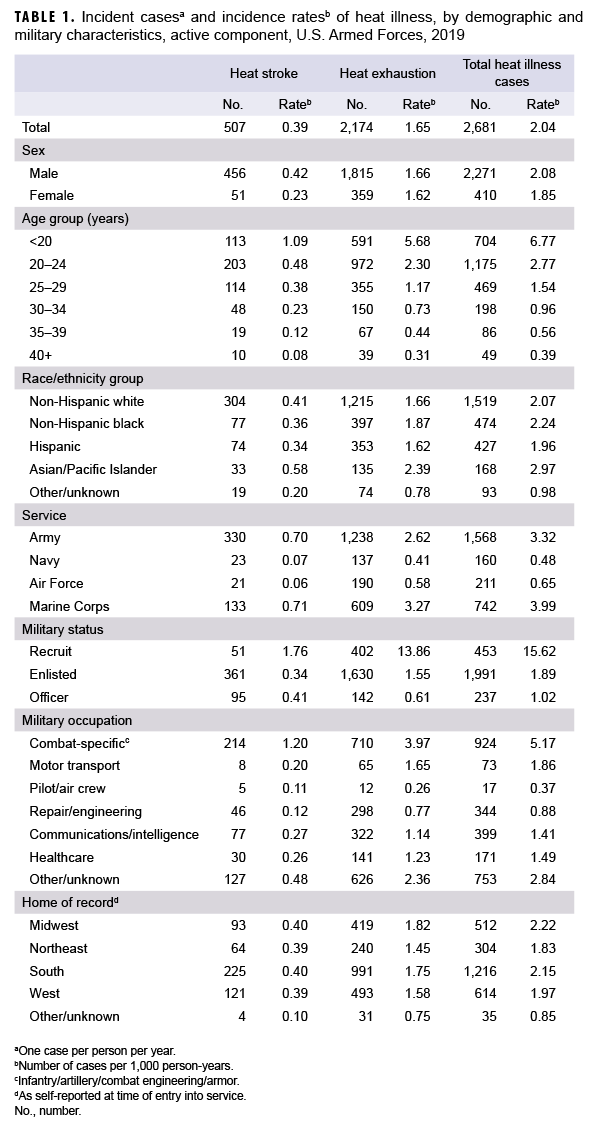

In 2019, there were 507 incident cases of heat stroke and 2,174 incident cases of heat exhaustion among active component service members. The overall crude incidence rates of heat stroke and heat exhaustion were 0.39 cases and 1.65 cases per 1,000 person-years, respectively. In 2019, subgroup-specific rates of incident heat stroke were highest among males, those less than 20 years old, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Marine Corps and Army members, recruit trainees, and those in combat-specific occupations. Subgroup-specific incidence rates of heat exhaustion in 2019 were notably higher among service members less than 20 years old, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Marine Corps and Army members, recruit trainees, and service members in combat-specific occupations. During 2015–2019, a total of 348 heat illnesses were documented among service members in Iraq and Afghanistan; 7.5% (n=26) were diagnosed as heat stroke. Commanders, small unit leaders, training cadre, and supporting medical personnel must ensure that the military members whom they supervise and support are informed about the risks, preventive countermeasures, early signs and symptoms, and first-responder actions related to heat illnesses.

What Are the New Findings?

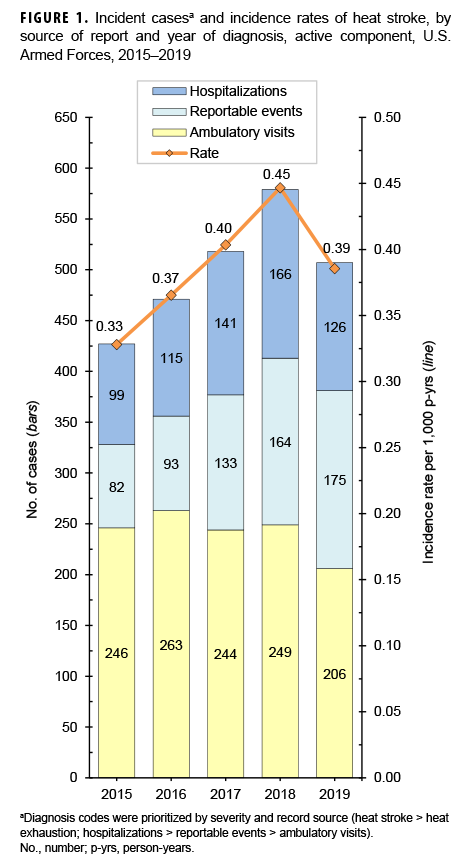

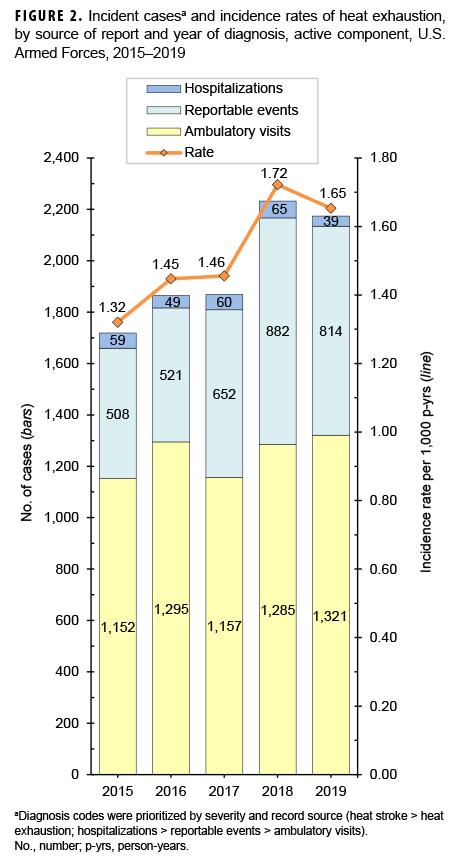

Annual rates of incident heat stroke and heat exhaustion cases among active component U.S. military members rose from 2015 through 2018 but then dropped in 2019. Although sizable proportions of heat stroke and heat exhaustion cases were not identified by way of mandatory reports through the Disease Reporting System internet (DRSi), the proportions of heat stroke cases identified via reportable medical events increased steadily between 2015 and 2019.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Heat stroke and heat exhaustion can reduce operational readiness by causing considerable morbidity, particularly during training of recruits and of Marine Corps and Army members in combat arms specialties. Complete and timely submission of mandatory reports of heat illness events ensures that local public health and command leaders have ready access to real-time surveillance data to identify trends and to guide preventive measures.

Background

Heat illness refers to a group of disorders that occur when the elevation of core body temperature surpasses the compensatory limits of thermoregulation.1 Heat illness is the result of environmental heat stress and/or exertion and represents a set of conditions that exist along a continuum from less severe (heat exhaustion) to potentially life threatening (heat stroke).

Heat exhaustion is caused by the inability to maintain adequate cardiac output because of strenuous physical exertion and environmental heat stress.1,2 Acute dehydration often accompanies heat exhaustion but is not required for the diagnosis.3 The clinical criteria for heat exhaustion include a core body temperature greater than 100.5ºF/38ºC and less than 104ºF/40ºC at the time of or immediately after exertion and/or heat exposure, physical collapse at the time of or shortly after physical exertion, and no significant dysfunction of the central nervous system. If any central nervous system dysfunction develops (e.g., dizziness or headache), it is mild and rapidly resolves with rest and cooling measures (e.g., removal of unnecessary clothing, relocation to a cooled environment, and oral hydration with cooled, slightly hypotonic solutions).1–4

Heat stroke is a debilitating illness characterized clinically by severe hyperthermia (i.e., a core body temperature of 104ºF/40ºC or greater), profound central nervous system dysfunction (e.g., delirium, seizures, or coma), and additional organ and tissue damage.1,4,5 The onset of heat stroke requires aggressive clinical treatments, including rapid cooling and supportive therapies such as fluid resuscitation to stabilize organ function.1,5 The observed pathologic changes in several organ systems are thought to occur through a complex interaction between heat cytotoxicity, coagulopathies, and a severe systemic inflammatory response.1,5 Multiorgan system failure is the ultimate cause of mortality due to heat stroke.5

Timely medical intervention can prevent milder cases of heat illness (e.g., heat exhaustion) from becoming severe (e.g., heat stroke) and potentially life threatening. However, even with medical intervention, heat stroke may have lasting effects, including damage to the nervous system and other vital organs and decreased heat tolerance, making an individual more susceptible to subsequent episodes of heat illness.6–8 Furthermore, the continued manifestation of multiorgan system dysfunction after heat stroke increases patients risk of mortality during the ensuing months and years.9,10

Strenuous physical activity for extended durations in occupational settings as well as during military operational and training exercises exposes service members to considerable heat stress because of high environmental heat and/or a high rate of metabolic heat production.11,12 In some military settings, wearing needed protective clothing or equipment may make it biophysically difficult to dissipate body heat.13,14 The resulting body heat burden and associated cardiovascular strain reduce exercise performance and increase the risk of heat-related illness.11,15

Over many decades, lessons learned during military training and operations in hot environments as well as a substantial body of literature have resulted in doctrine, equipment, and preventive measures that can significantly reduce the adverse health effects of military activities in hot weather.16–22 Although numerous effective countermeasures are available, heat-related illness remains a significant threat to the health and operational effectiveness of military members and their units and accounts for considerable morbidity, particularly during recruit training in the U.S. military.11,23 Moreover, with the projected rise in the intensity and frequency of extreme heat conditions associated with global climate change, heat-related illnesses will likely represent an increasing challenge to the military.24–26

In the U.S. Military Health System (MHS), the most serious types of heat-related illness are considered notifiable medical events. Notifiable cases of heat illness include heat exhaustion and heat stroke. All cases of heat illness that require medical intervention or result in change of duty status are reportable.4

This report summarizes reportable medical events of heat illness as well as heat illness-related hospitalizations and ambulatory visits among active component service members during 2019 and compares them to the previous 4 years. Episodes of heat stroke and heat exhaustion are summarized separately.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2015 through 31 Dec. 2019. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. All data used to determine incident heat illness diagnoses were derived from records routinely maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). These records document both ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the MHS) treatment facilities worldwide. In-theater diagnoses of heat illness were identified from medical records of service members deployed to Southwest Asia or the Middle East and whose health care encounters were documented in the Theater Medical Data Store. Because heat illnesses represent a threat to the health of individual service members and to military training and operations, the Armed Forces require expeditious reporting of these reportable medical events through any of the service-specific electronic reporting systems; these reports are routinely transmitted and incorporated into the DMSS.

For this analysis, a case of heat illness was defined as an individual with 1) a hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter with a primary (first-listed) or secondary (second-listed) diagnosis of heat stroke (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9]: 992.0; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10]: T67.0*) or heat exhaustion (ICD-9: 992.3–992.5; ICD-10: T67.3*–T67.5*) or 2) a reportable medical event record of heat exhaustion or heat stroke.27 Because of an update to the Disease Reporting System internet (DRSi) medical event reporting system in July 2017, the type of reportable medical events for heat illness (i.e., heat stroke or heat exhaustion) could not be distinguished using reportable medical event records in DMSS data. Instead, information on the type of reportable medical event for heat illness during the entire 2015–2019 surveillance period was extracted from the DRSi. It is important to note that MSMR analyses carried out before 2018 included diagnosis codes for other and unspecified effects of heat and light (ICD-9: 992.8 and 992.9; ICD-10: T67.8* and T67.9*) within the heat illness category "other heat illnesses". These codes were excluded from the current analysis and the April 2018 and April 2019 MSMR analyses. If an individual had a diagnosis for both heat stroke and heat exhaustion during a given year, only 1 diagnosis was selected, prioritizing heat stroke over heat exhaustion. Encounters for each individual within each calendar year then were prioritized in terms of record source with hospitalizations prioritized over reportable events, which were prioritized over ambulatory visits.

For surveillance purposes, a "recruit trainee" was defined as an active component service member (grades E1–E4) who was assigned to 1 of the services' 8 recruit training locations (per the individual's initial military personnel record). For this report, each service member was considered a recruit trainee for the period corresponding to the usual length of recruit training in his or her service. Recruit trainees were considered a separate category of enlisted service members in summaries of heat illnesses by military grade overall.

Records of medical evacuations from the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) (e.g., Iraq or Afghanistan) to a medical treatment facility outside the CENTCOM AOR were analyzed separately. Evacuations were considered case defining if affected service members had at least 1 inpatient or outpatient heat illness medical encounter in a permanent military medical facility in the U.S. or Europe from 5 days before to 10 days after their evacuation dates.

The new electronic health record for the MHS, MHS GENESIS, was implemented at 4 military treatment facilities in the state of Washington in 2017 (Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center). Implementation of the second wave of MHS GENESIS sites began in 2019 and included 3 facilities in California (Travis Air Force Base [AFB], the Presidio of Monterey, and Naval Air Station Lemoore) and 1 in Idaho (Mountain Home AFB). Medical data from facilities using MHS GENESIS are not available in the DMSS. Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities after their conversion to MHS GENESIS during 2017–2019 were not included in the current analysis.

Results

In 2019, there were 507 incident cases of heat stroke and 2,174 incident cases of heat exhaustion among active component service members (Table 1). The crude overall incidence rates of heat stroke and heat exhaustion were 0.39 and 1.65 per 1,000 person-years (p-yrs), respectively. In 2019, subgroup-specific incidence rates of heat stroke were highest among males, those less than 20 years old, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Marine Corps and Army members, recruit trainees, and those in combat-specific occupations (Table 1).The rates of incident heat stroke among Marine Corps and Army members were more than 10 times the rates among Air Force and Navy members. The incidence rate of heat stroke among service women was 44.8% lower than the rate among service men. There were only 51 cases of heat stroke reported among recruit trainees, but their incidence rate was more than 4 times that of other enlisted members and officers.

The crude overall incidence rates of heat exhaustion among males and females were close in value (1.66 per 1,000 p-yrs and 1.62 per 1,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Table 1).In 2019, compared to their respective counterparts, service members less than 20 years old, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Marine Corps and Army members, recruit trainees, and service members in combat-specific occupations had notably higher rates of incident heat exhaustion.

Crude (unadjusted) annual incidence rates of heat stroke increased steadily from 0.33 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2015 to 0.45 cases per 1,000 p-yrs in 2018 and then dropped to 0.39 cases per 1,000 p-yrs in 2019 (Figure 1).In the last year of the surveillance period, there were fewer heat stroke-related hospitalizations and ambulatory visits than in 2018 but more reportable medical events. The proportions of total heat stroke cases from hospitalizations remained relatively stable during 2015–2019 (range: 23.2%–28.7%). The proportions of total heat stroke cases from reportable medical events increased steadily over the course of the period (from 19.2% in 2015 to 34.5% in 2019), while the proportions of total cases from ambulatory visits decreased (from 57.6% in 2015 to 49.6% in 2019).

Crude annual rates of incident heat exhaustion increased between 2015 and 2016, were stable during 2016–2017, increased to a peak of 1.72 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2018, and then dropped to 1.65 per 1,000 p-yrs in 2019 (Figure 2). During the 5-year surveillance period, the proportions of total heat exhaustion cases from reportable medical events fluctuated between 27.9% and 39.5% and the proportions of cases from ambulatory visits varied between 57.6% and 69.4%. However, the proportions of heat exhaustion cases from hospitalizations remained relatively stable (range: 1.8%–3.4%).

Heat illnesses by location

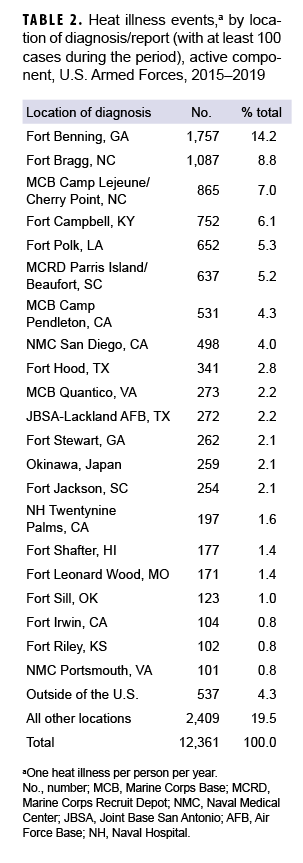

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 12,361 heat-related illnesses were diagnosed at more than 250 military installations and geographic locations worldwide (Table 2). Less than 5% of the total heat illness cases occurred outside of the U.S. (n=537). Four Army installations accounted for slightly more than one-third (34.4%) of all heat illnesses during the period (Fort Benning, GA [n=1,757]; Fort Bragg, NC [n=1,087]; Fort Campbell, KY [n=752]; and Fort Polk, LA [n=652]). Six other locations accounted for an additional one-quarter (25.4%) of heat illness events (Marine Corps Base [MCB] Camp Lejeune/Cherry Point, NC [n=865]; Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island/Beaufort, SC [n=637]; MCB Camp Pendleton, CA [n=531]; Naval Medical Center San Diego, CA [n=498]; Fort Hood, TX [n=341]; and MCB Quantico, VA [n=273]). Of these 10 locations with the most heat illness events, 7 are located in the southeastern U.S. The 21 locations with more than 100 cases of heat illness accounted for over three-quarters (76.2%) of all active component cases during 2015–2019.

Heat illnesses in Iraq and Afghanistan

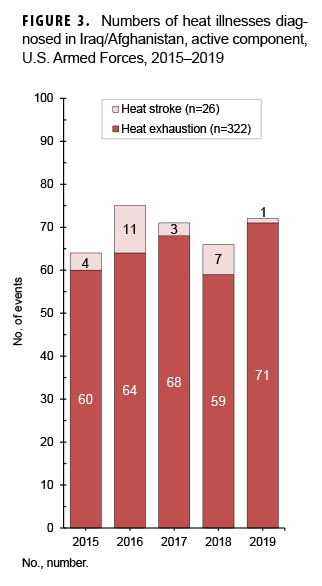

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 348 heat illnesses were diagnosed and treated in Iraq and Afghanistan (Figure 3). Of the total cases of heat illness, 7.5% (n=26) were diagnosed as heat stroke. Deployed service members who were affected by heat illnesses were most frequently male (n=291; 83.6%), non-Hispanic white (n=207; 59.5%), 20–24 years old (n=186; 53.4%), in the Army (n=180; 51.7%), enlisted (n=339; 97.4%), and in repair/engineering (n=110; 31.6%) or combat-specific (n=104; 29.9%) occupations (data not shown).During the surveillance period, 3 service members were medically evacuated for heat illnesses from Iraq or Afghanistan; all of the evacuations took place in the summer months (May–Sept.).

Editorial Comment

This annual update of heat illnesses among service members in the active component documented that the unadjusted annual rates of incident heat stroke increased steadily between 2015 and 2018 and then dropped in 2019. The crude annual incidence rate of heat exhaustion in 2019 represents a 13.7% decrease from the peak rate in 2018.

There are significant limitations to this update that should be considered when interpreting the results. Similar heat-related clinical illnesses are likely managed differently and reported with different diagnostic codes at different locations and in different clinical settings. Such differences undermine the validity of direct comparisons of rates of nominal heat stroke and heat exhaustion events across locations and settings. Also, heat illnesses during training exercises and deployments that are treated in field medical facilities are not completely ascertained as cases for this report. In addition, it should be noted that the guidelines for mandatory reporting of heat illnesses were modified in the 2017 revision of the Armed Forces guidelines and case definitions for reportable medical events and carried into the 2020 revision.4 In this updated version of the guidelines and case definitions, the heat injury category was removed, leaving only case classifications for heat stroke and heat exhaustion. To compensate for such possible variation in reporting, the analysis for this update, as in previous years, included cases identified in DMSS records of ambulatory care and hospitalizations using a consistent set of ICD-9/ICD-10 codes for the entire surveillance period. However, it also is important to note that the exclusion of diagnosis codes for other and unspecified effects of heat and light (formerly included within the heat illness category "other heat illnesses") in the current analysis precludes the direct comparison of numbers and rates of cases of heat exhaustion to the numbers and rates of "other heat illnesses" reported in MSMR updates before 2018.

As has been noted in previous MSMR heat illness updates, results indicate that a sizable proportion of cases identified through DMSS records of ambulatory visits did not prompt mandatory reports through the reporting system.23 However, this study did not directly ascertain the overlap between hospitalizations and reportable events and the overlap between reportable events and outpatient encounters. It is possible that cases of heat illness, whether diagnosed during an inpatient or outpatient encounter, were not documented as reportable medical events because treatment providers were not attentive to the criteria for reporting or because of ambiguity in interpreting the criteria (e.g., the heat illness did not result in a change in duty status, or the core body temperature measured during/immediately after exertion or heat exposure was not available). Underreporting is especially concerning for cases of heat stroke because it may reflect insufficient attentiveness to the need for prompt recognition of cases of this dangerous illness and for timely intervention at the local level to prevent additional cases.

In spite of its limitations, this report demonstrates that heat illnesses are a significant and persistent threat to both the health of U.S. military members and the effectiveness of military operations. Of all military members, the youngest and most inexperienced Marine Corps and Army members (particularly those training at installations in the southeastern U.S.) are at highest risk of heat illnesses, including heat stroke, exertional hyponatremia, and exertional rhabdomyolysis (see the other articles in this issue of the MSMR).

Commanders, small unit leaders, training cadre, and supporting medical personnel—particularly at recruit training centers and installations with large combat troop populations—must ensure that the military members whom they supervise and support are informed regarding the risks, preventive countermeasures (e.g., water consumption), early signs and symptoms, and first-responder actions related to heat illnesses.16–22,28–30 Leaders should be aware of the dangers of insufficient hydration on the one hand and excessive water intake on the other; they must have detailed knowledge of, and rigidly enforce countermeasures against, all types of heat illnesses.

Policies, guidance, and other information related to heat illness prevention and treatment among U.S. military members are available online through the Army Public Health Center website at https://phc.amedd.army.mil/topics/discond/.

References

- Atha WF. Heat-related illness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2013;31(4):1097–1108.

- Simon HB. Hyperthermia. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(7):483–487.

- O’Connor FG, Sawka MN, Deuster P. Disorders due to heat and cold. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 25th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:692–693.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Defense Health Agency. In collaboration with U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, Army Public Health Center, and Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center. Armed Forces Reportable Medical Events. Guidelines and Case Definitions, Jan. 2020. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2020/01/01/Armed-Forces-Reportable-Medical-Events-Guidelines. Accessed 1 April 2020.

- Leon LR, Bouchama A. Heat stroke. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(2):611–647.

- Epstein Y. Heat intolerance: predisposing factor or residual injury? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22(1):29–35.

- O’Connor FG, Casa DJ, Bergeron MF, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exertional heat stroke—return to duty/return to play: conference proceedings. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(5):314–321.

- Shapiro Y, Magazanik A, Udassin R, Ben-Baruch G, Shvartz E, Shoenfeld Y. Heat intolerance in former heatstroke patients. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(6):913–916.

- Dematte JE, O’Mara K, Buescher J, et al. Near-fatal heat stroke during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(3):173–181.

- Wallace RF, Kriebel D, Punnett L, Wegman DH, Amoroso PJ. Prior heat illness hospitalization and risk of early death. Environ Res. 2007;104(2):290–295.

- Carter R 3rd, Cheuvront SN, Williams JO, et al. Epidemiology of hospitalizations and deaths from heat illness in soldiers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(8):1338–1344.

- Hancock PA, Ross JM, Szalma JL. A meta-analysis of performance response under thermal stressors. Hum Factors. 2007;49(5):851–877.

- Caldwell JN, Engelen L, van der Henst C, Patterson MJ, Taylor NA. The interaction of body armor, low-intensity exercise, and hot-humid conditions on physiological strain and cognitive function. Mil Med. 2011;176(5):488–493.

- Maynard SL, Kao R, Craig DG. Impact of personal protective equipment on clinical output and perceived exertion. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162(3):180–183.

- 15. Sawka MN, Cheuvront SN, Kenefick RW. High skin temperature and hypohydration impair aerobic performance. Exp Physiol. 2012;97(3):327–332.

- Goldman RF. Introduction to heat-related problems in military operations. In: Lounsbury DE, Bellamy RF, Zajtchuk R, eds. Textbook of Military Medicine: Medical Aspects of Harsh Environments, Volume 1. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General; 2001:3–49.

- Sonna LA. Practical medical aspects of military operations in the heat. In: Lounsbury DE, Bellamy RF, Zajtchuk R, eds. Textbook of Military Medicine: Medical Aspects of Harsh Environments, Volume 1. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General; 2001:293–309.

- Headquarters, Department of the Army and Air Force. Technical Bulletin, Medical 507, Air Force Pamphlet 48-152. Heat Stress Control and Heat Casualty Management. 7 March 2003.

- Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, Department of the Navy. Marine Corps Order 6200.1E. Marine Corps Heat Injury Prevention Program. Washington DC: Department of the Navy; 6 June 2002.

- Navy Environmental Health Center. Technical Manual NEHC-TM-OEM 6260.6A. Prevention and Treatment of Heat and Cold Stress Injuries. Published June 2007.

- Webber BJ, Casa DJ, Beutler AI, Nye NS, Trueblood WE, O'Connor FG. Preventing exertional death in military trainees: recommendations and treatment algorithms from a multidisciplinary working group. Mil Med. 2016;181(4):311–318.

- Lee JK, Kenefick RW, Cheuvront SN. Novel cooling strategies for military training and operations. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(suppl 11):S77–S81.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Heat illness, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(4):15–20.

- Dahl K, Licker R, Abatzoglou JT, Declet-Barreto J. Increased frequency of and population exposure to extreme heat index days in the United States during the 21st century. Environ Res Commun. 2019;1:075002.

- Parsons IT, Stacey MJ, Woods DR. Heat adaptation in military personnel: mitigating risk, maximizing performance. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1485.

- Kenny GP, Notley SR, Flouris AD, Grundstein A. Climate change and heat exposure: impact on health in occupational and general populations. In: Adams W, Jardine J, eds. Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020:225–261.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance case definition: Heat illness. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2019/10/01/Heat-Injuries. Accessed on 1 April 2020.

- Headquarters, Department of the Army Training and Doctrine Command. Memorandum. TRADOC Heat Illness Prevention Program 2018. 8 Jan. 2018.

- Kazman JB, O’Connor FG, Nelson DA, Deuster PA. Exertional heat illness in the military: risk mitigation. In: Hosokawa Y, ed. Human Health and Physical Activity During Heat Exposure. Cham, Switzerland: SpringerBriefs in Medical Earth Sciences; 2018:59–71.

- 3Nye NS, O’Connor FG. Exertional heat illness considerations in the military. In: Adams W, Jardine J, eds. Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020:181–210.