A total of 254 febrile acute respiratory disease cases were identified among Army basic trainees in 2022. No Army basic training installations met the definition for an ARD or Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus outbreak in 2022. The inclusion of afebrile ARD data in the surveillance program identified an additional 1,696 cases in which a trainee met the criteria for a case of ARD, except for an oral temperature of 100.5°F or higher. While including afebrile cases in the ARD rate calculation did result in an overall increase in weekly ARD rates, no basic training installations met the MEDCOM definition for an ARD outbreak. The continued surveillance and implementation of interventions such as chemoprophylaxis, vaccination, and non-pharmacologic interventions (e.g. hand-washing, head-to-toe sleeping bunk arrangement, etc.) helped identify and potentially prevent ARD outbreaks.

What are the new findings?

In 2022, no ARD outbreaks were identified at any U.S. Army basic training installations, according to the U.S. Army’s Medical Command definition. This marks the third consecutive year without an ARD outbreak at these installations. Vaccination, chemoprophylaxis, and active disease surveillance are cornerstones of the Army’s program to protect the health and readiness of basic trainees, utilizing support from the Defense Health Agency’s Defense Centers for Public Health.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

U.S. Army basic training provides an ideal environment for the development of respiratory disease outbreaks because of sustained high stress combined with close trainee living and training quarters. Disease outbreaks degrade force readiness by increasing training time or potentially reducing numbers of trainees who graduate. The data from 2020 through 2022 demonstrate that no ARD outbreaks occurred in this population.

Background

Defense Centers for Public Health-Aberdeen conducts an active surveillance program for acute respiratory disease and Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus, under the oversight of the U.S. Army, at the 4 installations performing basic combat training or 1-station unit training.1 BCT is performed at 4 installations—Fort Moore (formerly Benning), Fort Jackson, Fort Leonard Wood, and Fort Sill—while OSUT, which includes advanced individual training immediately following BCT, is conducted only at Fort Moore and Fort Leonard Wood. The goal of this ARD surveillance program is to rapidly monitor, detect, and respond to outbreaks among basic trainees while evaluating the application of force health protection measures such as chemoprophylaxis, vaccination, and non-pharmacologic interventions.1-4

Two evidence-based preventive medicine tools to reduce the impact of ARD outbreaks are used by the U.S. Army in a practice called tandem antibiotic prophylaxis: vaccination and chemoprophylaxis.1,2,5,6 Upon arrival at any BCT or OSUT installation, trainees receive the adenovirus type 4 and type 7 live oral vaccines. Trainees who are not allergic to penicillin at Fort Moore (formerly Benning), Fort Leonard Wood, and Fort Sill also receive a single dose of benzathine penicillin G to eliminate a GABHS carrier state among incoming basic trainees and provide prophylaxis from GABHS in the first weeks of training. For trainees allergic to penicillin, either oral azithromycin or erythromycin is used as antibiotic prophylaxis. In contrast to other installations conducting BCT/OSUT, Fort Jackson is exempt from the tandem antibiotic requirement due to historically low ARD and GABHS activity.1,7

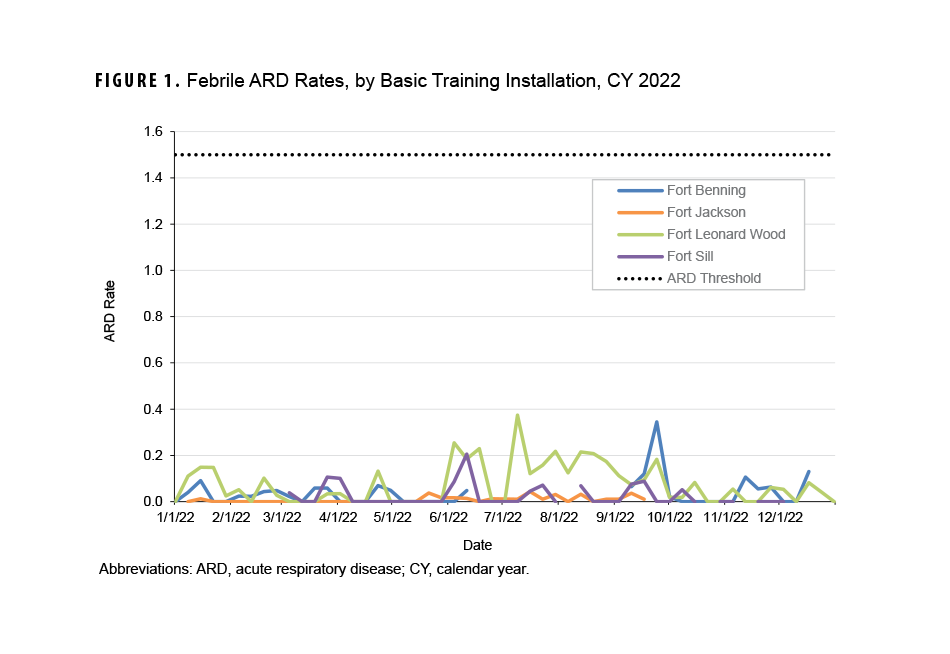

DCPH-A monitors BCT/OSUT installations through surveillance of ARD rates and the Strep-ARD Surveillance Index, which are obtained weekly from encounter and laboratory data collated by ARD program coordinators. The established outbreak definition, as stated in Office of the Surgeon General/MEDCOM Policy Memo 20-007, characterizes a potential outbreak, which prompts investigation at the installation, as 2 consecutive weeks in which the ARD rate exceeds 1.5 cases per 100 trainees and/or the SASI exceeds 25.1,7 Historically, this definition has served as an effective early warning signal that is highly suggestive of an outbreak.1,3,7

Methods

In calendar year 2022, DCPH-A received ARD data weekly from the program coordinators at Fort Benning, Fort Jackson, Fort Leonard Wood, and Fort Sill. Data were available for 38 weeks from Fort Benning, for 37 weeks from Fort Jackson, for 50 weeks from Fort Leonard Wood, and for 38 weeks from Fort Sill. Data were not collected during periods of block leave, or times when BCT/OSUT were not in session (weeks ending January 1, December 24, and December 31, 2022).

Program coordinators provided specified data to DCPH-A in a standardized spreadsheet: unit information, training course (e.g., BCT, OSUT, AIT), week of training, number of trainees, and ARD case count and streptococcal test information, stratified by sex. Units were excluded from weekly analyses if their training was AIT or OSUT in week 11 of training or later. Exclusions of trainees in AIT or the latter portions of OSUT are due to the fact that their living quarters are dormitory style, as opposed to open-air bays, and this living configuration greatly inhibits ARD transmission, as evidenced by the low ARD rates identified in the AIT population.8

To determine ARD cases for the weekly spreadsheet, ARD coordinators defined a case of febrile ARD as each of the following1:

- an oral temperature of 100.5°F or higher;

- recent onset of at least 1 sign or symptom of acute respiratory tract inflammation (e.g., sore throat, cough, runny nose, chest pain, shortness of breath, headache, tonsillar exudates, tender cervical lymphadenopathy); and

- and a limited duty profile signed by the examining medical provider that limited physical training and/or removed the Soldier from duty for at least 8 hours.

Beginning in February 2020, DCPH-A began collecting afebrile ARD cases for this surveillance program due to the rise in afebrile cases associated with pneumonia and streptococcal infection.1 The afebrile ARD case definition included criteria two and three of the febrile ARD case definition, with an oral temperature less than 100.5°F.

All febrile ARD cases should be tested for streptococcal infection in accordance with OTSG/MEDCOM Policy Memo 20-007.1 A positive test for streptococcal species on either a rapid streptococcal antigen test or a throat culture was considered to be a positive streptococcal test for a recruit trainee.

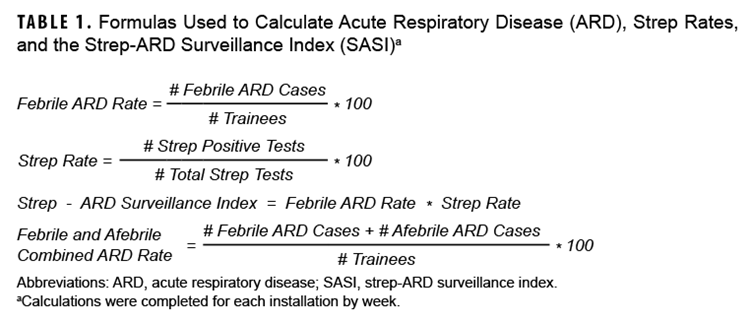

Data analysis was completed using SAS 9.4 software (Cary, NC). The calculations shown in Table 1 were completed for each installation by week.

Results

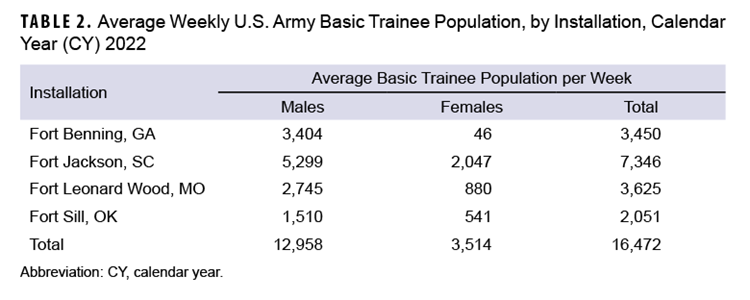

Fort Jackson trained the highest average weekly number (7,346) of new recruits in CY 2022, followed by Fort Leonard Wood (n=3,625), Fort Benning (n=3,450), and Fort Sill (n=2,051). The majority of trainees in 2022 were male (78.7%). Over half (58.3%) of the female trainee population was trained at Fort Jackson (Table 2).

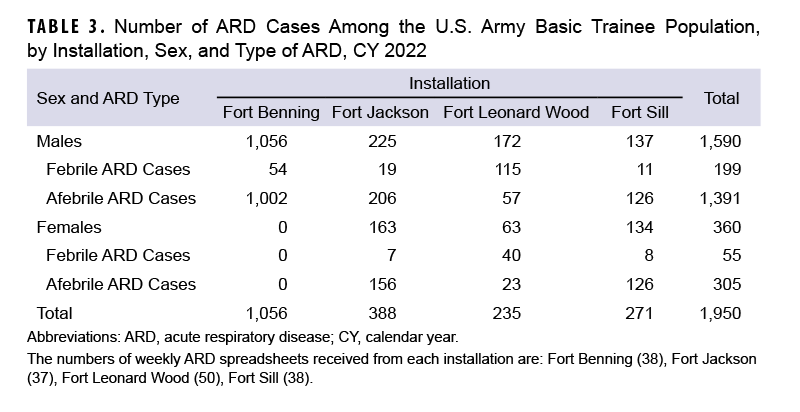

A total of 254 febrile ARD cases and 1,696 afebrile ARD cases were identified among Army trainees during CY 2022 (Table 3).

Febrile ARD

The febrile ARD rate recorded in CY 2022 for the four installations that conduct BCT and OSUT did not exceed the threshold of 1.5 cases per 100 trainees per week (Figure 1). Moreover, no installations saw a febrile ARD rate above 0.4 cases per 100 trainees per week during the CY. Increased ARD rates at the four installations were not sustained over numerous weeks during CY 2022.

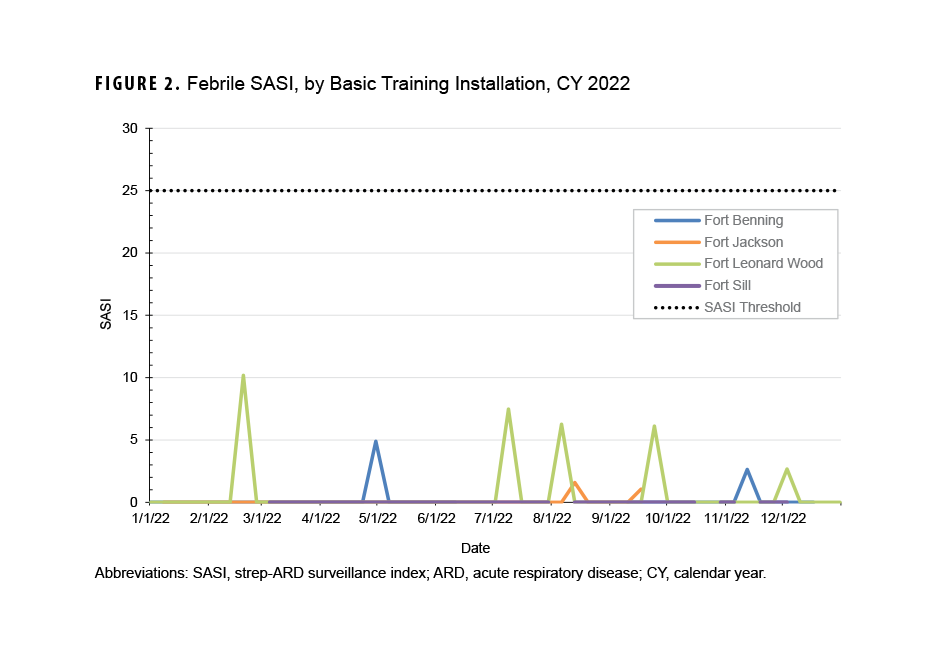

The febrile SASI did not exceed the index threshold of 25 per week during the CY (Figure 2). The highest SASI in CY 2022 was calculated for Fort Leonard Wood, for the week ending February 19, 2022. No installation had a SASI above zero for more than one week.

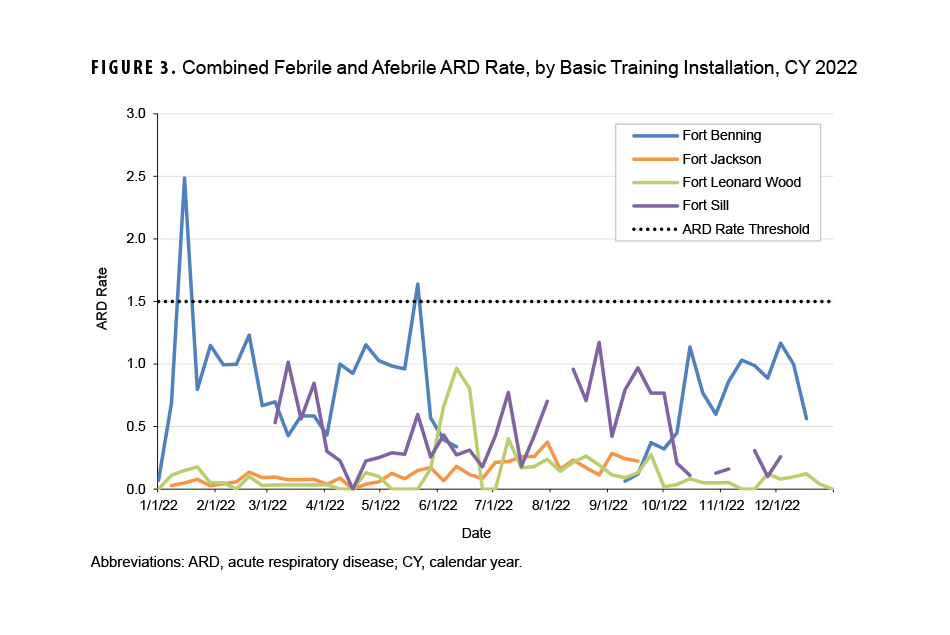

Febrile and Afebrile ARD

Twice during CY 2022 the combined ARD rate for febrile and afebrile cases at the four installations conducting BCT and OSUT exceeded the threshold of 1.5 cases per 100 trainees per week (Figure 3). Fort Benning’s combined ARD rate exceeded the ARD threshold on two separate weeks, ending January 15, 2022 and May 21, 2022; because the combined ARD rate did not exceed the threshold for two consecutive weeks, the definition for an ARD outbreak was not met.

Discussion

No U.S. Army basic training installations met the definition for an ARD outbreak in CY 2022. These findings are consistent with DCPH-A 2020 and 2021 ARD surveillance data, which also show no outbreaks during those periods. The results from this report also correlate with findings by Clemmons et al. that showed a significant and sustained decrease in ARD cases after the 2011 implementation of an adenovirus vaccine.9

These results emphasize the importance of continued vaccine administration among the Army basic trainee population. Army trainees are at a high risk for ARD and GABHS because bacteria and viruses naturally thrive in closed, crowded environments such as basic training settings. These pathogens are easily transmitted from person-to-person via respiratory droplets and can potentially cause respiratory infections.9

In addition to reporting cases of febrile and afebrile ARD, to prevent increases in the ARD and GABHS burden due to a disruption of vaccinations or chemoprophylaxis, program coordinators share information with DCPH-A on available BPG supplies at BCT/OSUT installations. If BPG is not available at an installation, DCPH-A can provide guidance on alternative chemoprophylaxis protocols as well as telephonic or on-site epidemiologic consultations.4,10

Secondary data from Fort Leonard Wood following a 2019 outbreak demonstrate that only 15% of ARD and streptococcal infections were febrile.10 The inclusion of afebrile cases has helped increase sensitivity and more accurately describe the burden, morbidity, and lost productivity associated with ARD previously not captured through the surveillance program.

The SASI was not calculated for afebrile ARD in this report because it is not a valid measure for evaluating streptococcal activity among afebrile ARD cases, as such cases do not require streptococcal testing for this surveillance program. For afebrile cases, a strep culture would only be ordered if clinically indicated, leading to fewer total strep cultures. Resulting strep rates could skew the SASI results.

The missing weeks of data from the BCT/OSUT installations is a limitation of this analysis. While multiple factors may have led to weekly ARD data not being submitted, the transition to the MHS GENESIS electronic medical record was identified as the leading cause. Despite missing data that affected the ARD rates and SASI-reported febrile and afebrile ARD cases during some weeks during the CY, DCPH-A was able to utilize the outbreak reporting tool in the Disease Reporting System internet as an additional method to identify potential outbreaks of ARD in the BCT/OSUT installations. The majority of missing Fort Benning data was from the summer, the majority of missing Fort Jackson data was from the fall, and the majority of missing Fort Sill data was from the winter.

DCPH-A continues to monitor, detect, and respond to ARD cases and potential outbreaks in the Army basic training environment. Based on the data obtained through the ARD Surveillance Program, Army installations conducting BCT/OSUT experienced no ARD outbreaks from 2020 to 2022.

References

- United States Army Medical Command. Acute Respiratory Disease and Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus Prevention Program. OTSG/MEDCOM Policy Memo 20-007, 2020.

- Webber BJ, Kieffer JW, White BK, Hawksworth AW, Graf PC, Yun HC. Chemoprophylaxis against group A streptococcus during military training. Prev Med. 2019;118:142-149. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.023

- Brundage JF, Gunzenhauser JD, Longfield JN, et al. Epidemiology and control of acute respiratory diseases with emphasis on group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus: a decade of U.S. Army experience. Pediatrics. 1996;97(6 Pt 2):964-970. doi:10.1542/peds.97.6.964

- U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine. Technical Guide 314: Non-Vaccine Recommendations to Prevent Acute Infectious Respiratory Disease Among U.S. Army Personnel Living in Close Quarters. May 2007. Accessed February 27, 2023. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/TG314_Non-vaccineRecommendationstoPreventAcuteInfectiousRespiratoryDisease.pdf

- Vento TJ, Prakash V, Murray CK, et al. Pneumonia in military trainees: a comparison study based on adenovirus serotype 14 infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(10):1388-1395. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir040

- McNamara LA, MacNeil JR, Cohn AC, Stephens DS. Mass chemoprophylaxis for control of outbreaks of meningococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(9):e272-e281. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30124-5

- Lee SE, Eick A, Ciminera P. Respiratory disease in army recruits: surveillance program overview, 1995–2006. Am J Prev Med. 2018;34(5):389-395. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.027

- White DW, Charles FW, Robert ME, Joseph HJ, James HR. Association between barracks type and acute respiratory infection in a gender integrated Army basic combat training population. Mil Med. 2011;176(8):909-914. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00418

- Clemmons NS, McCormic ZD, Gaydos JC, Hawksworth AW, Jordan NN. Acute respiratory disease in US army trainees 3 years after reintroduction of adenovirus vaccine. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(1):95-98. doi:10.3201/eid2301.161297

- U.S. Army Public Health Center. Epidemiological Consultation (EPICON) for Invasive Group A Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) Infections Among Basic Trainees at Fort Benning, 2019. PHR No. S.0047397-19 Executive Summary. 2019; ES1-ES5.

Author Affiliations

Defense Centers for Public Health-Aberdeen: Ms. Kotas, Dr. Trueblood, Dr. Superior (LTC, USA), Dr. Ambrose; Knowesis: Dr. Trueblood

Acknowledgements

DCPH-A wishes to thank the ARD program coordinators and reporters at Fort Moore, Fort Jackson, Fort Leonard Wood, and Fort Sill for their dedication and support of the ARD program and the protection of Army basic trainees.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy nor position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.