ABSTRACT

The crew of USS Kidd experienced a COVID-19 outbreak identified in April 2020. This is the earliest documented COVID-19 study with RT-PCR, serology, and pre-exposure test data on the entirety of the exposed population (n=333). Case definitions included 121 confirmed (36.3% of crewmembers) and 18 probable (5.4% of crewmembers) based on laboratory diagnostic test results. At the time of testing positive, 62 (44.6%) cases reported no symptoms. Hispanic ethnicity (AOR: 2.71, CI: 1.40-5.25) and non-smoker status (AOR: 2.28, CI: 1.26-4.12) were identified as statistically significant risk factors. This study highlights the value of rapid, onboard diagnostic testing to quickly identify an outbreak and enumerate cases, as well as the serological testing to flag potential cases missed with standard viral case identification methodologies.

What are the new findings?

One hundred twenty-one of the 333 crewmembers (36.3%) were confirmed COVID-19 cases. At the time of testing positive, 62 (44.6%) cases reported no symptoms. This high rate of asymptomatic infection presents a serious challenge to communicable disease control onboard ships.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

This report helps highlight the value of placing real-time diagnostic testing capabilities in outbreak scenarios with high transmission rates.

BACKGROUND

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been responsible for the largest respiratory illness pandemic since the influenza pandemic of 1918.1–3 After January 2020, when the first case of COVID-19 in the United States (U.S.) was identified, public health departments were quickly overwhelmed with outbreaks across the country.4 Ships were not exempt from the spread of the virus, as evidenced by outbreaks aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship and USS Theodore Roosevelt aircraft carrier. COVID-19 spread rapidly on those ships, and the outbreaks received international media attention early in the year 2020.5 The impact of respiratory virus outbreaks on the health and readiness of both naval and civilian shipboard populations has been well documented for both highly lethal and comparatively less virulent diseases. For example, in 1918, following a port of call to take on coal in Freetown, South Africa, a staggering 6.6% of the crew of the battleship HMS Africa died from influenza A (H1N1) infection while at sea.6 In the first instance of a widespread SARS-CoV-2 outbreak aboard ship, the Diamond Princess cruise ship outbreak demonstrated the virus’s ability to quickly spread throughout a confined population. Despite guest cabins allowing for isolation, 712 persons out of a total population of 3,711 (19.2%) on board the cruise ship became infected.7 Shortly thereafter, the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt experienced a COVID-19 outbreak during which 26.6% of the crew contracted a SARS-CoV-2 infection, with 1 fatality.5 Both of these outbreaks required substantial supplementary support to put an end to the fast-spreading infection.

In April 2020, the USS Kidd, a U.S. Navy guided missile destroyer on deployment in the Pacific Ocean, experienced a COVID-19 outbreak. Lessons learned from the USS Theodore Roosevelt outbreak prompted the dispatch of a Medical Rapid Response Team (RRT) from the Naval Medical Readiness and Training Command (NMRTC) Jacksonville and the amphibious assault ship USS Makin Island to provide increased medical support and critical care, as well as increased isolation and quarantine capacity, for several USS Kidd crewmembers while at sea. On 28 April, USS Kidd pulled into port in San Diego, CA. U.S. Naval Surface Force Pacific-Medical Readiness Division (SURFPAC-MRD) stood up Task Force Victory, which included members from the Navy Environmental and Preventive Medicine Unit FIVE (NEPMU-5), Navy Reserve (NR) Expeditionary Medical Facility (EMF) Camp Pendleton, and the Naval Health Research Center (NHRC), to answer the need for a fast and effective testing and care response for USS Kidd crewmembers. The objective of this report is to describe the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection within an unvaccinated, closely confined, and previously healthy crew of the USS Kidd using diagnostic, epidemiologic, and reported symptom data.

METHODS

Outbreak timeline

Outbreak investigations concluded that the initial COVID-19 exposure must have occurred sometime during a port visit from 9 March to 19 March 2020. The first suspected case was not identified until 11 April, while the USS Kidd was at sea, when a Sailor reported persistent COVID-like illness (CLI) symptoms. This Sailor was medically evacuated to shore several days later due to worsening symptoms and tested positive for COVID-19 on 22 April. The USS Makin Island arrived the following day, on 23 April 2020, to assist with outbreak response activities. The RRT embarked on 23 April with RT-PCR testing supplies and began testing suspect cases with nasal swabs (in addition to meeting other outbreak response needs). On 28 April USS Kidd arrived at Naval Base San Diego. Upon arrival, all crewmembers who had not already tested positive were tested with reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using nasopharyngeal swabs as they disembarked onto the pier. Additionally, all crewmembers were offered counseling and the option for serological blood testing for COVID-19. RT-PCR testing and serological blood sample processing were then completed at NHRC. Apart from a caretaker crew remaining on the ship, the crew were then individually quarantined or isolated on shore while receiving continued medical care and diagnostic testing. After 14 days, the caretaker crew went into quarantine or isolation and was replaced by crewmembers who had completed quarantine and had 2 negative RT-PCR COVID-19 tests.

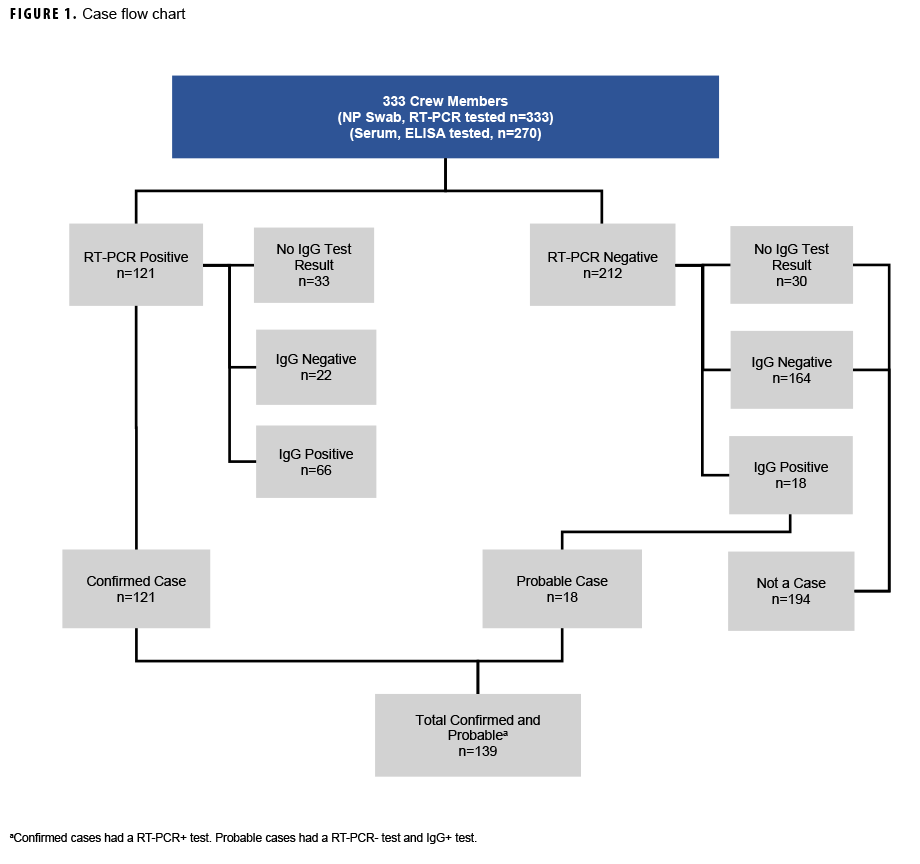

Prior to re-embarkation, along with RT-PCR tests crewmembers were again offered serological testing on 13 May 2020. Beginning 2 May 2020, crewmembers also submitted self-reports of symptoms experienced through the Defense Digital Service’s (DDS) The Dawn Project, a modified version of DDS’s mysymptoms.mil symptom checker application.8 All crewmembers were required to report absence or presence of symptoms twice a day on this electronic application while in quarantine or isolation. The last RT-PCR test was conducted on 15 June. The case definitions for confirmed, probable, and CLI cases are illustrated in Figure 1.

Sample population and study variables

Demographic data for military crews were pulled from the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS) and Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) personnel rosters from February 2020. Age at time of outbreak was calculated from date of birth as reported on 3 March 2020. Medical and symptomatic variables utilized for this analysis were assembled from information collected by the outbreak response team. Available data included work center/department, laboratory results, symptom information, and smoking status. Symptom data were supplemented by The Dawn Project symptom checker application.

Laboratory testing

Testing by RT-PCR for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus was conducted via 2 methods on 3 platforms. Initially, nasal swabs were processed for point-of-care testing with the Abbott 2020 ID NOW COVID-19 isothermal nucleic acid amplification test on board the ship until 28 April. Thereafter, nasopharyngeal swabs were collected into viral transport medium (VTM) for analysis on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Dx Real-Time PCR instrument or on a bio-Mérieux BioFire FilmArray Torch platform. Samples were processed for viral nucleic acid extraction by the Qiagen QiaAmp-Viral RNA mini kit, and RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 was performed using the CDC’s Emergency Use Authorization RT-PCR assay.

RT-PCR testing for non-COVID-19 respiratory viral pathogens was performed on a Luminex MAGPIX instrument with the FDA-approved NxTag Respiratory Pathogen Panel. This tested nasopharyngeal/VTM samples for the presence of nucleic acids from influenza A (pan)/A-H1/A-H3, influenza B (pan), respiratory syncytial virus A/B, rhinovirus/enterovirus, parainfluenza viruses 1/2/3/4, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, and the seasonal coronaviruses HKU1/NL63/229E/OC43.

Serology samples voluntarily donated on 28 April or 13 May (whole blood collected by venipuncture) were collected and processed by NHRC and stored as serum. For each crew member who provided a serum specimen, an individually matched serum sample was obtained from the DOD Serum Repository, consisting of the most recent serum sample collected prior to October 2019, which served as a negative control for samples collected during the outbreak. All serum samples were tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reactive to the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein from Epitope Diagnostics. Tests were performed on an automated Dynex DS2 instrument.

Case definitions

A "confirmed" case was defined as a USS Kidd crewmember with a RT-PCR positive test. A "probable" case was defined as a USS Kidd crewmember with an IgG positive serology test and a negative RT-PCR test. Given the lack of diagnostic testing capabilities that highlighted the importance of symptomatic screening during the early days of the pandemic,9,10 a symptom-based COVID-19-like illness (CLI) classification was also developed in this paper, although it was not included within the definition of a COVID-19 case. Crewmembers included within this classification exhibited symptoms consistent with COVID-19 but IgG and IgM serological testing was negative, or RT-PCR test results were negative, and additional respiratory panel testing conducted retrospectively by NHRC after the outbreak was contained was also negative. Symptomatic cases were grouped into 2 categories of known COVID-19 symptoms at the time of the outbreak, based on the 5 April 2020 Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) published clinical criteria. These criteria included at least 1 of the following: cough or shortness of breath (Category A); or at least 2 of the following: fever, chills, body aches, headaches, sore throat, and altered taste or smell (Category B).11

Confirmed and probable cases were further classified as symptomatic (symptom onset before first positive laboratory test), pre-symptomatic (first positive laboratory test before subsequent symptom onset), or no symptoms reported (positive laboratory test but never met clinical criteria) utilizing CSTE published criteria noted above.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) and R statistical software version 3.6.2 (R Core Team, 2019). Frequencies, attack rates, and unadjusted odds ratios across all case classifications (confirmed, probable, and CLI) were calculated; adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were generated to control for all study demographic and military variables without missing data. Lastly, the symptom presentations for each case classification were compared using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and a significance level of 5% (P<0.05).

Institutional review

The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol, number NHRC.2020.0007.

RESULTS

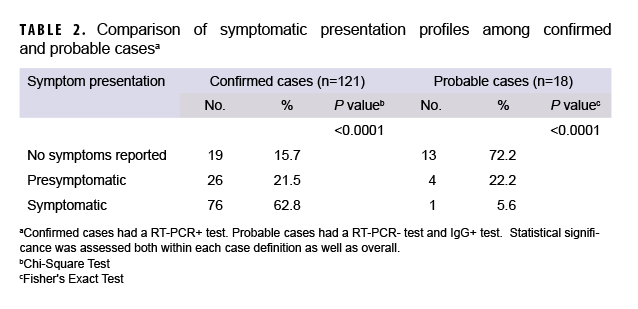

The crew were predominantly young adults (31.5% were 22-25 years of age), male (82.3%), White (50.8%), enlisted (83.2%), and self-reported as non-smokers (76.3%) (Table 1). One hundred twenty-one of the 333 crewmembers (36.3%) were confirmed COVID-19 cases. A total of 270 crewmembers (81.1%) volunteered to provide additional blood samples for serological testing. An additional 18 probable cases (5.4%) were identified by the presence of serum IgG antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 virus. Additional laboratory testing for non-COVID-19 respiratory viral pathogens was conducted retrospectively on 75 crewmembers, including: all probable cases (n=18), all crewmembers classified as CLI (n=17) and 40 randomly selected COVID-19-negative crewmembers. Only 1 positive case for bocavirus and 1 positive case for rhinovirus were identified, and neither of those cases were within the probable case group (or CLI classification). Of the 139 confirmed and probable cases, 77 (55.4%) were symptomatic, 32 (23.0%) reported no symptoms, and 30 (21.6%) were pre-symptomatic at the time of testing. Additionally, 13 (72.2%) of the 18 cases that were discovered through serology testing also had no symptoms at the time of RT-PCR testing (Figure 1 and Table 2). All results for IgM testing aligned with IgG positivity.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of cases over time by earliest symptoms of infection. Based on symptom onset data, the outbreak appears to have expanded in 3 waves, with each wave successively larger than the previous. When cases were graphed based on diagnosis date (subset by first symptom of infection for asymptomatic cases), the peak of the outbreak shifted from 2 May to 25 April.

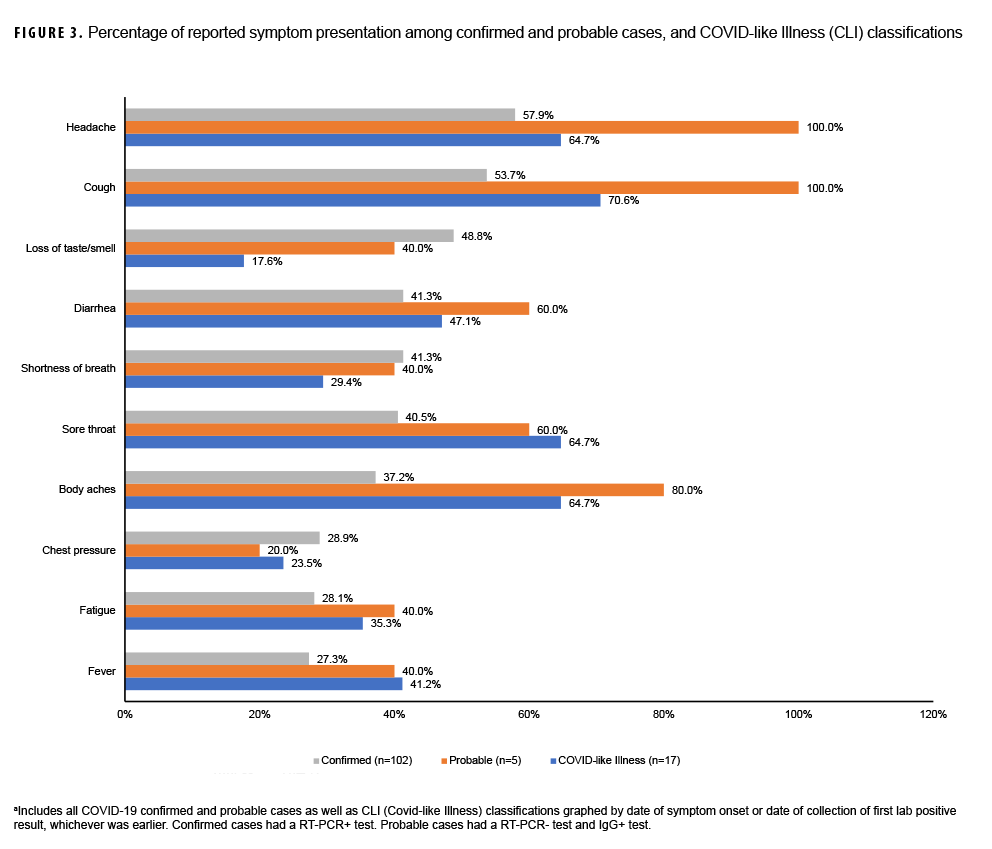

When looking at symptom presentation, the top 10 reported symptoms among the 3 COVID-19 case definitions are depicted in Figure 3. Confirmed (58%) and probable (100%) cases reported headache the most. Loss of taste or smell, a unique symptom of COVID-19 illness, showed similar proportions among confirmed (49%) and probable (40%) cases. Shortness of breath also was experienced similarly among confirmed (41%) and probable cases (40%). Reports of fever were greater among probable cases (40%) than among confirmed cases (27%). Additionally, there were statistically significant differences in reported symptoms, as evidenced in Table 2 across all 3 symptom categories: no symptoms, pre-symptomatic, and symptomatic.

Of the 194 crewmembers who tested negative through both methodologies, 17 crewmembers fit the CLI classification due to reporting symptomatic profiles consistent with the 5 April 2020 CSTE published criteria.11 These 17 crewmembers also had negative RT-PCR test results and negative IgG/IgM serology, and also had negative results from additional respiratory panel testing conducted retrospectively by NHRC after the outbreak was contained. Figure 3 demonstrates that CLI cases most often reported cough (71%) and least often reported a loss in taste or smell (18%).

Hispanic ethnicity was found to be associated with COVID-19 positivity, with an adjusted odds ratio and confidence interval of 2.71 (1.40-5.25) (Table 1). Interestingly, being a smoker was associated with a lower risk of becoming a confirmed case, as non-smokers had an adjusted odds ratio and confidence interval of 2.28 (1.26-4.12). There were no other significant findings among the additional military and demographic characteristics of rank, sex, or age.

Lastly, 9 crewmembers were sent to the emergency department (ED); and while all were eventually confirmed cases, 2 of these 9 were initially referred to the ED for mental health reasons. Five crewmembers were hospitalized for COVID-19-related treatment needs (average length of the first hospital stay was 2.8 days), and no cases were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The COVID-19 outbreak aboard USS Kidd illustrates the speed and breadth with which a highly transmissible respiratory virus can disseminate through closed congregate settings where social distancing measures are not possible, and the population is immunologically naïve. With an attack rate of 41.7%, nearly half of the ship population tested positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR or IgG diagnostic testing. A unique aspect of this outbreak response was the use of a RRT bringing RT-PCR testing capabilities aboard the ship shortly after identification of the first case. This resulted in the outbreak peaking 3 days after embarkation of the team and before the ship pulled into port. In fact, 64 of the 139 cases (46.0%) were diagnosed between 23 April, when the RRT embarked, and 27 April, the day before arriving to port in San Diego. By shifting case counts earlier in time, outbreak response was able to start earlier. Of note, this RT-PCR equipment was not a normal organic asset present on most ships.

Comprehensive diagnostic testing during this outbreak further improved understanding of how vital laboratory support was to identify and mitigate respiratory illnesses through serological testing capabilities once in port in San Diego. An additional 5% of the crew who were likely infected with COVID-19 had tested negative by RT-PCR. Confidence in the validity of the serological detection of COVID-19 within these probable cases was higher due to the use of individually matched pre-pandemic negative control samples obtained from the DOD Serum Repository. Only one sample from the serum repository showed an inconclusive serological reactivity for SARS-CoV-2, as opposed to a negative or positive result, to which this same individual then tested negative in April 2020 when re-tested. At the time of this study, average rates of asymptomatic infection by SARS- CoV-2 in the community were about one third of cases.12 This high rate of asymptomatic infection presents a serious challenge to communicable disease control aboard ships where syndromic cases presenting at morning sick call is often the first notice of an outbreak.

At the time of testing positive, 62 (44.6%) of cases reported no symptoms, including 13 of the 18 cases that tested positive by serology but negative by RT-PCR. For symptomatic cases, the majority of confirmed cases presented as symptomatic or pre-symptomatic (84%). The majority of probable cases, however, had no symptoms reported (72%), as illustrated by Table 2. One study suggested that the global prevalence for loss of taste or smell for those with COVID-19 was about 48%, a comparable percentage to the symptomatic confirmed case group from USS Kidd (49%), and slightly higher than the symptomatic probable cases (40%), who also exhibited loss of taste or smell.13 A loss of taste or smell has been a key symptom separating COVID-19 cases from other respiratory illnesses.14 With less than half of cases from this outbreak reporting this symptom, however, loss of taste or smell should not be considered a reliable indicator of COVID-19 infection when diagnosing a respiratory illness.

The CLI classification was explored due to the unique circumstances of containing outbreaks on a military vessel where testing for respiratory pathogens is limited or non-existent. Had diagnostic testing not been available, USS Kidd would have had to rely on identifying cases based on the accepted symptom presentation for a COVID-19 case at that time. Additionally, the wealth of laboratory diagnostic data for an enumerated population permitted the investigative team to conduct additional testing to support the conclusion that no other pathogens were responsible for CLI symptom presentations at the time of the outbreak. Without diagnostic capabilities, these crewmembers would have been considered cases, and it is curious they exhibited COVID-like symptoms yet failed to test positive via RT-PCR or IgG. Had it been possible, follow up serological testing for COVID-19 on the crew (and particularly these members) would have been interesting. Additional possible causes for their reported symptoms could be non-infection-related causes such as: allergies, responses to weather (e.g., colder days may lead to runny noses, etc.), responses to not enough sleep (i.e., resulting in fatigue or headaches), or other factors that should be considered in future investigations of CLI classifications.

Given the size of USS Kidd and its dense population, most departments showed attack rates higher than 30%, with only the Air department lower, at 27% (Table 1). The close confines of shipboard spaces present intrinsic challenges to social distancing and other public health measures. Crewmembers continue to be inherently vulnerable to outbreaks of novel respiratory pathogens.15 This outbreak also showed an increased risk of infection among those of reported Hispanic ethnicity, even when controlling for department and rank. While racial and ethnic disparities have been identified for COVID-19 infection,16 further research is needed to eliminate any possible confounders not accounted for within this analysis (e.g., shared duty stations, meal arrangements, etc.) in order to best mitigate risk factors in future COVID-19 outbreaks. Another curious finding is that smokers were less likely to be diagnosed as cases. While literature has found that smoking increased the risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, the research at the time of this study was inconclusive about whether it may mitigate risk of contracting the virus.17 One study that investigated the literature on nicotine's prophylactic potential for COVID-19 found not enough evidence reliably available for this theory, with more research needed to study this aspect of possible COVID-19 risk factors.18

In addition, medical care received by USS Kidd's crew highlighted the complexity of responding to a shipboard outbreak; 9 crewmembers were sent to the emergency department (ED), but not all were for direct COVID-19 treatment reasons. While all were eventually confirmed cases, 2 of these 9 were initially referred to the ED for mental health reasons. Although not directly related to COVID, being in isolation, combined with the stress of being infected with a novel virus, may have contributed to the mental health issues.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, symptoms were self-reported and therefore potentially underreported; the reported experience of COVID-19 symptoms led many patients to discount their illness, particularly when mild and construed as “allergy related.” As symptom data were collected through a variety of methods, this potential bias is likely limited. Second, given that this outbreak occurred prior to readily accessible RT-PCR testing onboard, it is possible the number of potential cases (RT-PCR negative but IgG positive cases) would have been RT-PCR positive cases if tested earlier. Furthermore, symptoms may also not have been reported reliably in these earlier cases due to potential recall bias, leading to an overestimation of asymptomatic cases. Prior infection unrelated to the USS Kidd outbreak is unlikely, based on the absence of prior infection from serologic samples provided in December 2019, coupled with the fact that the ship was underway a few months after that collection point, leading to a very small window for new infection to occur unrelated to time aboard the Kidd. RT-PCR sampling was not homogeneous in methodology throughout the duration of the outbreak, as evidenced by one RT-PCR platform using nasal swabs at sea and another using nasopharyngeal swabs in port. These differences could lead to inaccurate test results; however, crewmembers were tested multiple days while in quarantine or isolation in port and therefore had the opportunity for verifying prior test results.

In addition, it was not possible to directly measure other potential shipboard exposure risk factors such as frequency of use of personal protective equipment (PPE). When USS Kidd departed its port of call on 20 March 2020, there was no mask requirement in place, and limited medical grade masks were available for distribution. It was not until 6 April 2020 that crewmembers were instructed to use undershirts as makeshift cloth face coverings. The timing of face covering initiation and consistency of PPE use may have contributed to differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection risk.

Conclusion

This study is one of several that highlights the complexities of responding to a highly infectious respiratory virus outbreak among a shipboard population. It also highlights the value of serology in documenting a complete picture of an outbreak by identifying additional cases that evade detection by syndromic surveillance and molecular testing. Rapid, onboard diagnostic testing of the entire crew informed case identification and isolation measures, likely contributing to an earlier peak of cases during the outbreak and possibly leading to fewer cases. This report helps highlight the value of placing real-time diagnostic testing capabilities in outbreak scenarios with high transmission rates. While the urgency of COVID-19 has dissipated, respiratory illness-caused pandemics are still a very real threat, and public health agencies responsible for preventive and responsive actions should take the time now to dissect the many layers that exist within a novel respiratory virus outbreak.

With respect to COVID-19, continued study is warranted as largely vaccinated crews undertake future deployments, to understand the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks underway and the characteristics of those outbreaks.

Author affiliations

Naval Hospital Bremerton (CDR Legendre, CAPT Feinberg); Naval Health Research Center (Ms. Boltz, Dr. Myers); Leidos, Inc. (Ms. Boltz); Navy & Marine Corps Public Health Center (Ms. Jindal Riegodedios, Ms. Luse, Ms. Glasheen, Ms. Poitras); 4th Marine Logistics Group, 4th Medical Battalion, Surgical Company Bravo (LT Brown); Naval Hospital Jacksonville (CAPT Kaplan); Commander, Naval Surface Force Pacific Fleet (LCDR Sullivan); Navy Environmental Preventive Medicine Unit No. 5 (LCDR Whiting); II Marine Expeditionary Force (CAPT Hollis).

Disclaimer

No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper. The contents described in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of the Department of Defense.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript would not have been possible without the combined diversified efforts from the many personnel who responded to the outbreak, as well as those personnel who created and managed the data utilized for this report. The authors would like to thank the following personnel, in no particular order, for their especially vital roles needed for this publication to be a success. From the civilian world, the authors thank Ms. Courtney Cook for all her efforts to reorganize the original data, identify strengths and weaknesses of the data, and ultimately collate the data into an analyzable dataset. Thanks go to Dr. Edward Gorham for his subject matter expertise in epidemiological study design utilized for these analyses, and Mr. James Bonkowski for his statistical analysis expertise. From the military world, the authors thank CAPT Kimberly Davis and CAPT Jeffrey Stancil from 4th Fleet, as well as LCDR Clifton Wilcox from NMRTC Jacksonville and HMC Clinton Barton from USS Kidd for providing crucial background information and context to the outbreak, which informed the study design and methods for this analysis. Thanks also to CAPT Robert Francis Jr., CAPT Ann Mott, CAPT Andrew Baldwin, CDR Shawn Harris, CDR Kelly Yannizzi, LT Aaron Perreault, and LT Alison Matsunaga from the SURFPAC/MRD/USNR teams for their help in planning, executing, medically treating, and overseeing the screening, testing, and isolation or quarantine of USS Kidd sailors. In regard to the intricate ways data are collected during an outbreak, the authors thank CDR Gary Brice (NEPMU-5) for providing support for the numerous testing evolutions, as well as LCDR Teshome Taffes (NEPMU-2), HM2 Bradley Williams (NEPMU-5), and HM3 Erique Lynn (NEPMU-5) for providing support for case interviews and documentation. Thanks also to CDR Rebecca Welch for lending expertise to troubleshoot methods and review draft write-ups. Finally, this analysis would never have been possible without the dedication and commitment of the many commands who supported data collection throughout this outbreak including USS Kidd, NMRTC Jacksonville, MRD-San Diego, and EMF Camp Pendleton.

References

- Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270-273. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

- Feehan J, Apostolopoulos V. Is COVID-19 the worst pandemic? Maturitas. 2021;149:56-58. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.02.001

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929-936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

- Kasper MR, Geibe JR, Sears CL, et al. An outbreak of Covid-19 on an aircraft carrier. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2417-2426. doi:10.1056/NEJ-Moa2019375

- Shanks GD, Waller M, MacKenzie A, Brundage JF. Determinants of mortality in naval units during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(10):793-799. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70151-7

- Tokuda Y, Sakihama T, Aoki M, et al. COVID-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in February 2020. J Gen Fam Med. 2020;21(4):95-97. doi:10.1002/jgf2.326

- Dawn Project. The Dawn Project. Accessed March 8, 2022. https://dawnproject.com/

- Dollard P. Risk assessment and management of COVID-19 among travelers arriving at designated U.S. airports, January 17–September 13, 2020. MMWR. 2020;69. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a4

- Hamilton JJ, Turner K, Lichtenstein Cone M. Responding to the pandemic: challenges with public health surveillance systems and development of a COVID-19 national surveillance case definition to support case-based morbidity surveillance during the early response. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27:S80. doi:10.1097/ PHH.0000000000001299

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020 Interim Case Definition. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/coronavirus-disease-2019-2020/. Approved April 5, 2020. Accessed February 18, 2022.

- Oran DP, Topol EJ. The proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic. Ann Intern Med. Published online January 22, 2021:M20-6976. doi:10.7326/M20-6976

- Ibekwe TS, Fasunla AJ, Orimadegun AE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of smell and taste disorders in COVID-19. OTO Open. 2020;4(3):2473974X20957975. doi:10.1177/2473974X20957975

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Similarities and Differences Between Flu and COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/flu-vs-covid19.htm. Published January 18, 2022. Accessed February 18, 2022.

- Vera DM, Hora RA, Murillo A, et al. Assessing the impact of public health interventions on the transmission of pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus aboard a Peruvian navy ship. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2014;8(3):353-359. doi:10.1111/irv.12240

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community, Work, and School. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/racial-ethnic-disparities/increased-risk-illness.html. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2022.

- Shastri MD, Shukla SD, Chong WC, et al. Smoking and COVID-19: what we know so far. Respir Med. 2021;176:106237. doi:10.1016/j. rmed.2020.106237

- Korzeniowska A, Reka G, Bilska M, Piecewicz-Szczesna H. The smoker’s paradox during the COVID-19 pandemic? The influence of smoking and vaping on the incidence and course of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection as well as possibility of using nicotine in the treatment of COVID-19--Review of the literature. Przegl Epidemiol. 2021;75(1):27-44. doi:10.32394/pe.75.03