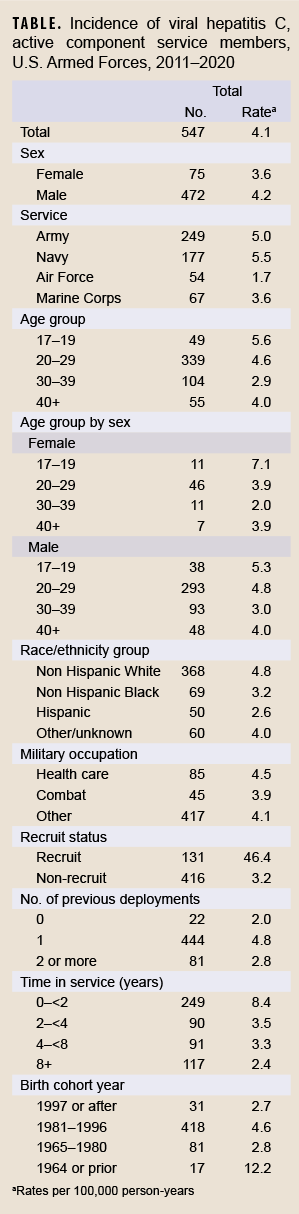

This study reports updated numbers and incidence rates of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among active component members of the U.S. military using a revised case definition during a 10-year surveillance period between 2011 and 2020. During the surveillance period, there were 547 incident cases of HCV infection, resulting in an overall incidence rate of 4.1 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs), which was much lower than that seen in the general U.S. population. The incidence rate trended downward from 4.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2011 to 1.6 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020. Incidence of HCV infection was higher in males, those identifying as non-Hispanic White, Navy members, those in healthcare occupations, and among those in the youngest age category (17–19 years). When stratified by year of birth, the incidence of hepatitis C was highest among those born in 1964 or prior; however, when stratified by time in service, incidence was highest among those with less than 2 years of military service. The updated incidence of and factors associated with HCV infection in the U.S. military provided in this report may be useful in evaluating the impact of current HCV screening policies and in guiding updates to them.

What are the new findings?

During the surveillance period, there were 547 incident cases of HCV infection in the U.S. military, resulting in an overall incidence rate of 4.1 per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs), which was much lower than the rate seen in the general U.S. population. The incidence rate declined from 4.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2011 to 1.6 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

The updated incidence of and factors associated with HCV infection in the U.S. military provided in this report may be useful in evaluating the impact of current HCV screening policies and in guiding updates to them. When present, HCV infection can be a challenge for an individual service member’s health. Additionally, in a combat zone, HCV-infected service members may be a source of HCV exposure and transmission to fellow service members in the event of a need for emergency blood transfusion for combat casualties. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common cause of chronic viral hepatitis in the United States.1 HCV can cause significant inflammatory damage to the liver, resulting in complications including cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and fulminant liver failure. In the U.S., it has been estimated that 4.1 million persons possess HCV antibodies, and that 2.4 million of these individuals are currently infected.2 In the U.S. military, HCV infection presents a concern not only for an individual service member’s fitness for duty and operational readiness, but it also poses a risk of transmission to uninfected service members during emergency situations in combat when utilizing a walking blood bank for whole blood transfusions is deemed necessary.3 Additionally, the significant morbidity and cost of treatment for the long-term, adverse health outcomes of chronic HCV infection could burden the Military Health System (MHS) and Veterans Administration.

The impact of HCV on the MHS includes newly acquired cases of acute HCV infection as well as asymptomatic chronic HCV-infected individuals entering military service. Recent MSMR publications have estimated the prevalence of HCV during military service to be 5.2 per 100,000 and found that all or nearly all active HCV cases identified during military service are chronic cases.4

A validation study published in the September 2022 issue of the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) found that the HCV case definition used in previous studies published in the MSMR overestimated the burden of confirmed HCV by 39%.5 The study recommended changing the HCV case definition to include only those individuals identified as cases via the reportable medical event (RME) system.

Because this new case definition would result in lower sensitivity, it was also recommended that the Department of Defense (DOD) should establish a method to ensure that hepatitis C laboratory data are entered into the RME system to improve accuracy and completeness of reporting. The aim of this study was to report updated numbers and incidence rates of HCV infection among members of the U.S. military using this revised case definition during the 10-year surveillance period from 2011 through 2020.

Methods

Data for this study were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which relates demographic information to health care encounters involving active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces in direct and purchased care. The DMSS also contains reportable medical events from the military’s reportable event notification system, the Disease Reporting System internet (DRSi). The surveillance period was 1 January 2011 through 31 December 2020. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. Data from the DMSS included year of diagnosis, demographics (race and ethnicity, sex, service, age, years in service, military occupation, recruit status, birth cohort year, and number of deployments).

Each case was defined by having a record of a notifiable medical event that specified a confirmed diagnosis of hepatitis C. The DOD case definition for confirmatory evidence of HCV includes a positive nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA, which includes qualitative, quantitative, or genotype testing; a positive HCV antigen test; or anti-HCV test conversion (from negative to positive within a 12-month period).6 The incident date was the date of the earliest confirmed reportable medical event. Each individual could be an incident case only once per lifetime. Prevalent cases (i.e., cases identified prior to the start of the surveillance period) were excluded. The combined incidence rates of both acute and chronic hepatitis C were calculated per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) of service. Because RMEs often do not distinguish the type of HCV (acute or chronic), and because the validation study found that almost all service member cases of HCV were chronic,5 this study did not attempt to distinguish acute vs. chronic HCV. However, it can be presumed that all or almost all cases identified in this report are chronic HCV.

Results

During the 10-year surveillance period, there were 547 incident cases of hepatitis C, resulting in an overall crude (i.e., unadjusted) incidence rate of 4.1 per 100,000 p-yrs. (Table). The incidence rate trended downward from 4.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2011 to 1.6 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020 (Figure). The lowest incidence rate observed other than 2020 was 2.9 per 100,000 in 2018 and the highest rate was 7.6 per 100,000 in 2013.

Incidence of hepatitis C infection was higher in males compared to females, those identifying as non-Hispanic White race and ethnicity as compared to non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic, and among those in the youngest age category (17–19 years) compared to older age categories. In addition, incidence was higher among Navy members compared to members in other service branches, among those with a single prior deployment compared to 0 or 2 or more deployments, and among those in healthcare occupations compared to combat or other occupations. Of note, the incidence of hepatitis C among recruits (46.4 per 100,000 p-yrs) was more than 14 times that of non-recruits (3.2 per 100,000 p-yrs). When stratified by year of birth, the incidence of hepatitis C was highest among those born in 1964 or prior; however, when stratified by time in service, incidence was highest among those with less than 2 years of military service.

Editorial Comment

This report documents a decline in annual crude incidence rate of HCV infection among active component service members, with all annual rates during the 5 years of 2016 through 2020 being lower than the average rate for the entire 10-year surveillance period. The highest incidence rate of HCV infection was among recruits, with a rate 14 times that of non-recruits. By age, group rates were highest among those who were 17–19 years of age. Overall rates were also highest among those in the Navy, and among those who had < 2 years in service. These observations were expected in light of the universal Navy and Marine Corps HCV policy screening which occurs in basic training and are thus counted in this report.6 Nevertheless, the birth cohort of individuals born in or prior to 1964 (i.e., ages 46 and older during the surveillance period) also had a higher rate of infection than other birth cohorts.

The risk factors for and decreasing trend in HCV incidence demonstrated by the current study largely mirror the findings for chronic HCV in a prior study of U.S. military service members from 2008–2016.7 However, the rates of chronic HCV from these two studies remain notably different, where the current report (4.1 per 100,000 from 2011–2020) was substantially lower than the rate reported in the prior study (12.2 per 100,000 from 2008–2016). This difference may be explained by the continued decline in HCV incidence over the two intervals studied, in addition to a potential for overreporting (39%) inherent to the case definition employed in the study from 2008–2016, as documented in a sensitivity analysis from the September 2022 MSMR validation study.5 In contrast, the case definition used in the current report is expected to underreport the true HCV disease burden by 29.5%. The combination of the overreporting when using the previous case definition and underreporting when using the one in this report would be expected to result in a 49.5% lower rate in this study compared to the previous report.

The 2018 rate of chronic HCV disease estimated from the current study of the U.S. active component (2.9 per 100,000) was demonstrably lower than the civilian population rate (54.1 per 100,000 in 2018) reported in the same year.8 This was not due to the confounding effects of age, as 20–29 year old had a much lower incidence in the military over the 10-year reporting period compared to the general U.S. population in 2018 (4.6 vs. 72.0 per 100,000); 30–39 year old had a similarly lower incidence (2.9 vs. 95.0 per 100,000).8 Instead, this is likely due to several other factors, such as the prohibition of and regular screening for drug use in the U.S. military, as well as the screening for and exclusion of individuals with medical conditions from military service, including untreated HCV.9 The individuals who are found to have chronic HCV during basic training screening are then discharged from military service for HCV which is "existing prior to service." They may then reapply for military service after they receive successful treatment and obtain documentation of cure 12 weeks after completion of therapy.9

The factors associated with HCV infection in the U.S. military were generally similar to those with chronic HCV in the U.S. civilian population, with higher incidence among men, younger ages, White non-Hispanic individuals, and those born during or before 1964.1,8 Differences included a peak incidence among the 17–19 years of age in the military as compared to 30–39 years in the civilian population, which may be partially attributable to the universal screening which was performed among recruits starting in 2012 in the Navy and Marine Corps. Additionally, the highest incidence in the civilian population was seen among individuals with race and ethnicity reported as American Indian or Alaska Native, which was categorized as “other” in the military due to small numbers. Although the decreasing trend of HCV in the military may have been partially due to the recruit screening program instituted in the Navy and Marine Corps, a similar decrease in chronic HCV incidence was also seen in the civilian population between 2011 to 2019 (from 185,979 cases in 2011 to 123,312 in 2019).1,10 However, civilian rates have much more variability because of the inconsistent number of states reporting chronic HCV from year to year.

The most important limitation of this study is underreporting of HCV infection, since most chronic (and acute) HCV infections often go undiagnosed because they are asymptomatic.8,11 This may be particularly true of calendar year 2020 due to the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in restricting access to health care. Therefore, the numbers and rates of HCV infection diagnoses reported here may underestimate the true rates of new infections among active component U.S. military members. The revised case definition also has limitations in sensitivity and positive predictive value which were quantified previously,5 and these should be considered when comparing to military studies that used the previous MSMR case definition.7 Furthermore, a surveillance bias is introduced in the Navy and Marine Corps due to the HCV screening program instituted among recruits in those services in 2012, which complicates comparisons with military medical records prior to 2012 and with civilian populations. Finally, although the cases described in this report are all newly diagnosed and may be called incident cases, previous studies have shown that all or nearly all of the cases are chronic, with almost no acute cases.4 Due to this chronic nature, and since the primary risk factors for these infections existed prior to entry into military service (e.g., injection drug use, contact with an HCV infected case),1 it is likely that most of these infections occurred prior to military service rather than during it. Thus, these newly diagnosed “incident” cases have many features of prevalent cases due to this more chronic nature.

Per current Department of Defense (DOD) accession standards, individuals are medically disqualified if they display a “history of chronic hepatitis C, unless successfully treated and with documentation of a cure 12 weeks after completion of a full course of therapy.”9 Prior to accession, applicants are required to submit a medical history and undergo service-specific medical screening procedures.7 Since 2012, the Navy and Marine Corps have required all new applicants to undergo HCV screening prior to entering military service.6 The Army and Air Force, however, currently do not require HCV testing at accession, and the Navy and Marine Corps have not instituted testing among any populations other than recruits.

The findings of this report may inform a re-evaluation of HCV screening policies by providing an assessment of the impact of the existing service-specific laboratory screening procedures. It may also help guide public health policy makers to determine if a DOD-wide screening policy should be established, as suggested in previous reports.4,11The current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation is for universal HCV screening among adults “except in settings where the prevalence is <0.1%.”12 While the estimated prevalence of HCV in the U.S. military is actually less than this (0.04%),11 other factors may make a compelling case for screening, such as the estimated 88% of HCV cases which are undiagnosed in the military, and the risk of transmission by undiagnosed blood donors who are part of the “walking blood bank” during emergent transfusion while deployed.4,13

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report, United States, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/index.htm. Accessed 20 September 2022.

- Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013-2016. Hepatology 2019;69(3):1020-1031.

- Ballard T, Rohrbeck P, Kania M, Johnson LA. Transfusion-transmissible infections among U.S. military recipients of emergently transfused blood products, June 2006-December 2012. MSMR 2014;21(11):2-6.

- Legg M, Seliga N, Mahaney H, Gleeson T, Mancuso JD. Diagnosis of hepatitis C infection and cascade of care in the active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2020. MSMR 2022;29(2):2-7.

- Mancuso J, Seliga N, Legg M, Stahlman S. Evaluation of the MSMR surveillance case definition for incident cases of hepatitis C. MSMR 2022;29(9):10-14.

- Office of the Secretary of the Navy. SECNAV INSTRUCTION 5300.30E: Management of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the Navy and Marine Corps. Department of the Navy. https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/NMFA/NMCPHC/root/Field%20Activities/Pages/NEPMU6/Operational%20Support/Preventive%20Medicine/SECNAVINST-5300.30E-HIV-and-Hepatitis.pdf. Accessed 20 September 2022. Updated 13 August 2012.

- Stahlman S, Williams VF, Hunt DJ, Kwon PO. Viral hepatitis C, active component, U.S. military service members and beneficiaries, 2008-2016. MSMR 2017;24(5):12-17.

- Ryerson AB, Schillie S, Barker LK, Kupronis BA, Wester C. Vital signs: Newly reported acute and chronic hepatitis C cases - United States, 2009-2018. MMWR 2020;69(14):399-404.

- Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03: Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_v1p.PDF?ver=9NsVi30gsHBBsRhMLcyVVQ%3D%3D. Accessed 20 September 2022. Updated 6 May 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Viral Hepatitis Surveillance, United States, 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2011surveillance/pdfs/2011HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf. Accessed 20 September 2022.

- Brett-Major DM, Frick KD, Malia JA, et al. Costs and consequences: Hepatitis C seroprevalence in the military and its impact on potential screening strategies. Hepatology 2016;63(2):398-407.

- Schillie S, Wester C, Osborne M, Wesolowski L, Ryerson AB. CDC recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults - United States, 2020. MMWR 2020;69(2):1-17.

- Hakre S, Peel SA, O'Connell RJ, et al. Transfusion-transmissible viral infections among US military recipients of whole blood and platelets during Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Transfusion 2011;51(3):473-85.