Rotavirus gastroenteritis is the leading cause of diarrhea-associated morbidity and mortality among children under age 5 worldwide.1 RotaTeq vaccine was approved in 2006 for the prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants 6 to 32 weeks of age, followed by Rotarix in 2008. However, vaccination coverage for children aged 19–35 months remained well below 50% in the United States (U.S.) in 2009 and rose to only 73% in 2017.2 In contrast, vaccination coverage for inactivated polio virus (IPV) and diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP), two long-standing and highly trusted pediatric vaccines, averaged 93% and 84%, respectively, between 2009 and 2017.2 Even when vaccine acceptance is high, degree of delay is of concern: A national study of children born between 2004 and 2008 reported that 49% were undervaccinated for at least 1 day before age 24 months.3

There is a paucity of published research on recent pediatric vaccine coverage among military beneficiaries. A 2015 study identified military children as potentially at risk for lower vaccination rates than their civilian counterparts: 28% of military dependents vs 21% of all other children aged 19–35 months had not completed the recommended immunization series.4 Notably, this study relied on data reported by primary care providers. As military beneficiaries are more likely to move and may access care at both military and civilian facilities, the information provided by a single provider may be incomplete. No prior study of military beneficiaries has examined timeliness of pediatric vaccinations relative to the recommended age of vaccination.

The present study used the Military Health System (MHS) immunization registry and medical encounter data to assess: 1) rotavirus vaccine coverage relative to IPV and DTaP vaccines and 2) trends in pediatric under vaccination among a population of infants born to female active duty service members.

Methods

Department of Defense Birth and Infant Health Research (BIHR) program data were used to identify infants born to female active duty service members from 2006 through 2016.5 The BIHR program is an ongoing population-based surveillance and research effort that identifies and follows infants born to military families (i.e., TRICARE beneficiaries). BIHR data consist of military demographic and personnel data from the Defense Manpower Data Center and the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System, and administrative medical encounter data from the MHS Data Repository. Same-sex multiple births are excluded from BIHR data due to difficulty distinguishing their neonatal medical records. Infants included in the present study were required to be enrolled in TRICARE within the first 12 months of life and then continuously enrolled until 24 months of age.

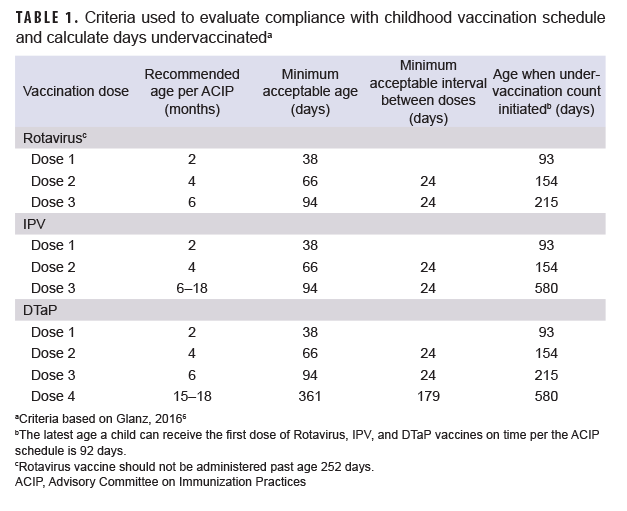

Immunization status was principally assessed using the MHS immunization database, which is populated with immunizations given at military clinics. These data were supplemented with immunizations identified using Current Procedural Terminology codes (90680, 90681, 90713, 90696, 90697, 90698, 90723, 90700) in outpatient health care records from military clinics and civilian facilities. Completion of rotavirus (2 doses), IPV (3 doses), and DTaP (4 doses) vaccination was assessed by 24 months of age. Vaccine compliance was assessed by additionally applying the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices childhood immunization schedule (Table 1).6 Doses received early were not considered, while those received after the recommended vaccination window were recorded as delayed and not compliant. Due to limited information on vaccine product in the MHS database, the 2 dose Rotarix requirement (vs the 3 dose RotaTeq requirement) was applied for rotavirus vaccine completion and compliance.

Service member (sponsor) factors of interest included age at delivery (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, or 35+ years), race and ethnicity (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, or other/unknown), marital status (married or unmarried/unknown), military rank (enlisted or officer), service branch (Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marine Corps, or Navy), and deployment within 24 months postpartum (yes or no). Health care factors of interest included birth location (civilian facility or military clinic), primary well-childcare location (according to the location of the majority of care, either at civilian facilities or military clinics), change of well-childcare location (by catchment area) before age 24 months (yes or no), and infant enrollment type (TRICARE Prime or other).

Completion and compliance were calculated annually (2006–2016), overall, and by sponsor and health care characteristics. For calculations by sponsor and health care characteristics, rotavirus vaccine was required among infants born after 2008. All data management and descriptive statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

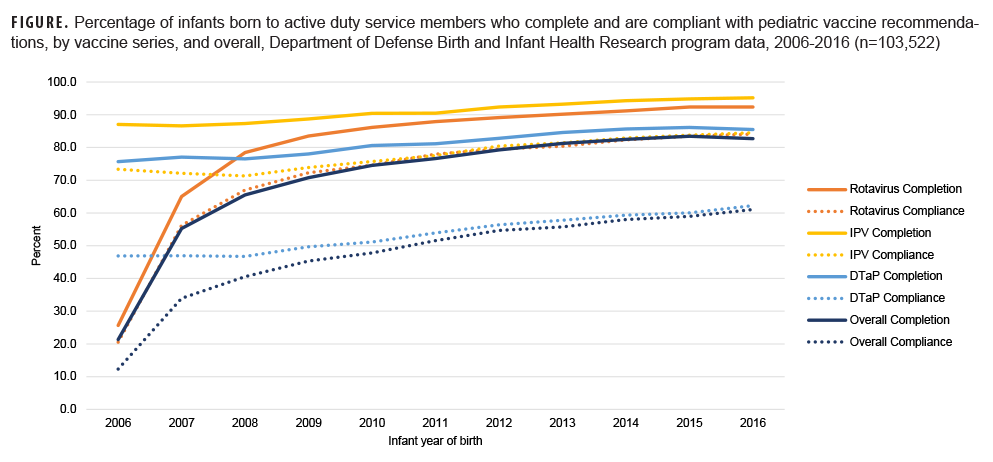

Overall, 103,522 infants were identified for vaccination assessment. Rotavirus vaccine completion increased from 2007 (the first full year after vaccine approval) to 2016 (2007: 65.0%, 2016: 92.4%; Figure); however, the rate of uptake slowed after 2009 and completion never achieved levels of IPV, which remained consistently high throughout the study time frame (2006: 87.0%, 2016: 95.2%). After 2007, vaccine completion was lowest for DTaP (2008: 76.5%, 2016: 85.5%), and DTaP compliance only reached 62.3% in 2016. Low DTaP compliance was due in large part to 14.5% of infants not receiving the fourth dose of the vaccine and another 8.6% with no previous delays in vaccination receiving the fourth dose after age 15-18 months. For infants born between 2014 and 2016, approximately 40% remained under vaccinated for at least 1 day before age 24 months, and 12.5% were under vaccinated for more than 6 months.

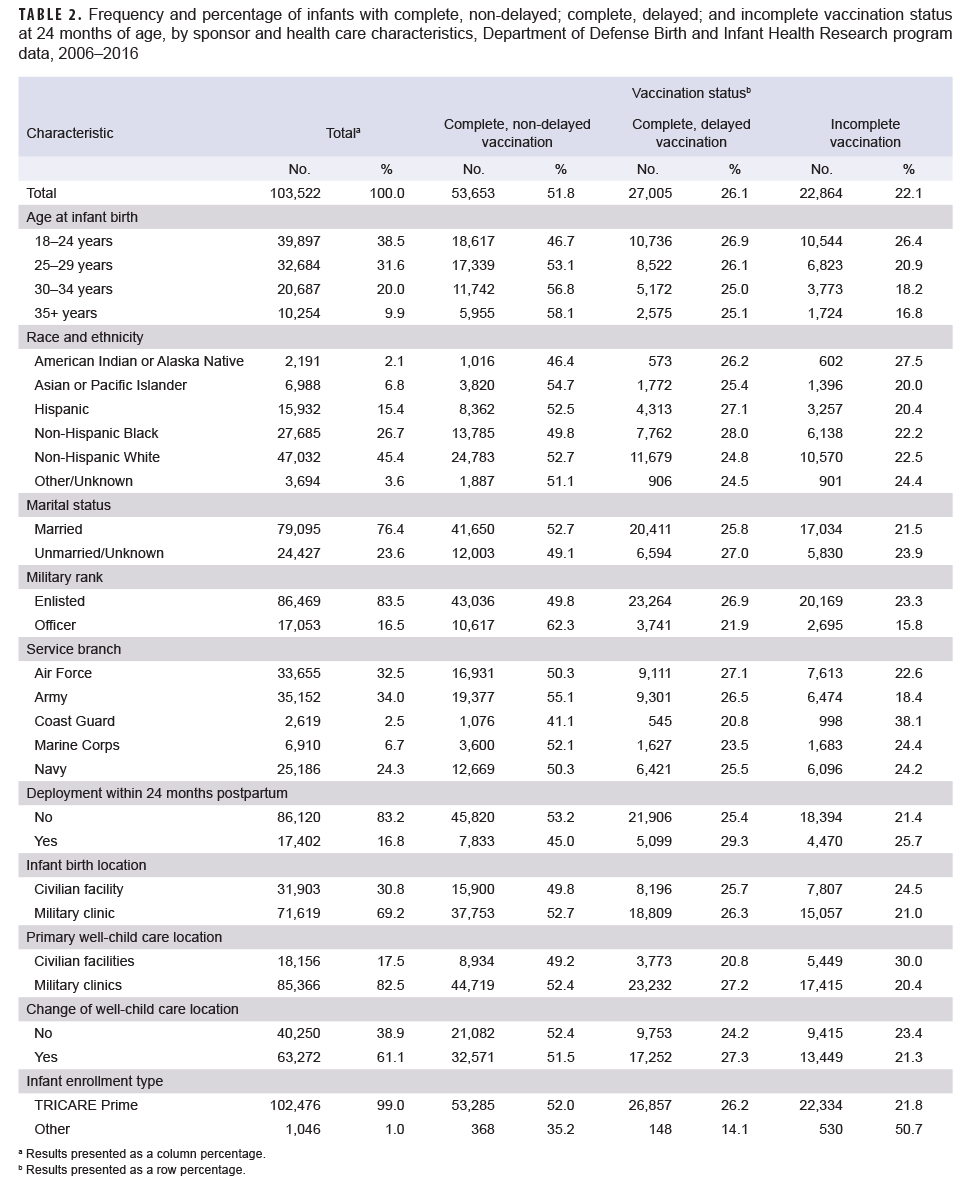

Vaccination coverage varied by select sponsor and health care characteristics, particularly for incomplete vaccination status (Table 2). Infants born to older service members, service members of officer rank, and service members who did not deploy within 24 months postpartum were more likely to be completely vaccinated without delays (35+ vs 18–24 years: 58.1% vs 46.7%; officer vs enlisted: 62.3% vs 49.8%; not deployed vs deployed: 53.2% vs 45.0%). Asian or Pacific Islander service members had the highest rate of infant non-delayed vaccine completion (54.7%), followed by non-Hispanic White and Hispanic service members (52.7% and 52.5%, respectively). Non-Hispanic Black and American Indian or Alaska Native service members had the lowest rates of non-delayed vaccine completion (49.8% and 46.4%, respectively). Infants born to service members in the Army were more likely to complete all vaccinations on time relative to other service branches (55.1%), while infants born to Coast Guard branch members were the least likely to have complete, non-delayed vaccination (41.1%). Infants who primarily received care at military clinics versus civilian facilities were more likely to experience delays in vaccination (27.2% vs 20.8%), but less likely to be incomplete with their vaccinations at 24 months (20.4% vs 30.0%). Vaccination coverage was similar by marital status, infant birth location, and change of well-childcare location. Although sample size was small, incomplete vaccination appeared more likely among infants enrolled in other types of TRICARE versus those enrolled in TRICARE Prime.

Editorial Comment

Rotavirus vaccination of infants born to active duty service members commenced in 2006, following RotaTeq approval. By 2009, rotavirus vaccine completion among these military dependents had surpassed that observed nationally for children aged 19-35 months (83.5% vs 43.9%). Although the gap had narrowed by 2016, the infants in this study continued to exhibit higher vaccine completion (92.4% vs 74.1%).2 IPV and DTaP vaccine series completion began below national rates but achieved comparable levels by 2012, with coverage exceeding national rates after 2013.1 Despite overall improvements in vaccine series completion, incomplete and delayed vaccination remained prevalent for DTaP and varied by select characteristics: some differences paralleled national findings (e.g., by maternal age and race and ethnicity2,4,7)others were distinct to the active duty population (e.g., by military rank, service branch, and deployment status).

The present work adds to the literature on childhood vaccination among military dependents. Findings corroborate prior vaccine completion estimates of 84.0–85.7% for 24-month-old military dependents8,9 however, there were also stark gaps between vaccine completion and compliance. Differences by demographic characteristics indicate the need for improved communication between providers and parents, while those by primary care location underscore the need for improved data and information flow between civilian and military health care providers.10 Relatively low vaccine completion rates among infants born to Coast Guard and deployed sponsors may be related to unique barriers to coordinated care for these infants, including fragmented care and childcare challenges associated with living in remote or geographically isolated areas.10-12 Recent evidence suggests vaccine hesitancy may be increasing in the U.S.,13 including within the MHS: parental hepatitis B vaccination refusal rates for infants born in the MHS increased from 2014 to 2018, despite a concurrent increase in vaccination coverage.14 Provider-parent communication about vaccine significance and safety, and provider attention to access-related barriers are therefore increasingly important for vaccine series compliance.

In this study, detailed infant vaccination records and continuous TRICARE enrollment enabled ascertainment of timing and type of vaccination. Although capture of vaccination status is therefore presumed close to comprehensive, it is possible that some vaccinations, e.g., those received at civilian inpatient facilities, were not documented in the immunization record. This may in part explain higher incompletion rates among infants whose well-childcare visits were predominantly at civilian facilities. As rotavirus measurement did not account for the fact that the RotaTeq vaccine requires a third dose, true coverage (i.e., receipt of all rotavirus doses in the series) may also be lower than reported here.

Military providers should continue to promote rotavirus vaccination alongside vaccination for IPV and DTaP, and ensure infants return for a care visit during the 15- to 18-month age window in order to remain compliant with the DTaP series. Additional work is needed to understand the causes of delayed vaccination and identify opportunities for delay prevention.

Author affiliations

Leidos, Inc., San Diego, CA (Ms. Romano, Ms. Bukowinski, Dr. Hall, Ms. Burrell, Ms. Gumbs); Deployment Health Research Department, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Ms. Romano, Ms. Bukowinski, Dr. Hall, Ms. Burrell, Ms. Gumbs, Dr. Conlin); Department of Pediatrics, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA (Dr. Ramchandar).

Disclaimer

Drs. Conlin and Ramchandar are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. This work was supported by the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery under work unit 60504 and by the Defense Health Agency Immunization Healthcare Division Intramural Studies Program under proposal ID IHBISP-19-002. The views expressed in this research are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government. The study protocol was approved by the Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. Research data were derived from an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol, number NHRC.1999.0003.

References

- GBD Diarrhoeal Diseases Collaborators. Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(9):909-948.doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30276-1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Table 31. Vaccination coverage for selected diseases among children aged 19-35 months, by race, Hispanic origin, poverty level, and location of residence in metropolitan statistic area: United States, selected years 1998–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2018/031.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2022.

- Glanz JM, Newcomer SR, Narwaney KJ, et al. A population-based cohort study of under vaccination in 8 managed care organizations across the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(3):274-281. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.502

- Dunn AC, Black CL, Arnold J, Brodine S, Waalen J, Binkin N. Childhood vaccination coverage rates among military dependents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1148-56. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2101.

- Bukowinski AT, Conlin AMS, Gumbs GR, Khodr ZG, Chang RN, Faix DJ. Department of Defense Birth and Infant Health Registry: Select reproductive health outcomes, 2003–2014. MSMR. 2017;24(11):39-49.

- Glanz JM, Newcomer SR, Jackson ML, et al. White paper on studying the safety of the childhood immunization schedule in the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Vaccine. 2016;34(1):A1-A29. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.082

- Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kang Y. Vaccination coverage among children aged 19-35 months-United States, 2016. MMWR. 2017;66:1171-77.

- Nestander M, Dintaman J, Susi A, Gorman G, Hisle-Gorman E. Immunization completion in infants born at low birth weight. JPIDS. 2018;7(3):e58-e64. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix079

- Lopreiato JO, Ottolini MC. Assessment of immunization compliance among children in the department of defense health care system. Pediatrics. 1996;97:6.

- Kaufman J, Tuckerman J, Bonner C, Durrheim DN, Costa D, Trevena L, Thomas S, Danchin M. Parent-level barriers to uptake of childhood vaccination: a global overview of systematic barriers. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(9):e006860. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006860

- Coast Guard Health Care: Improvements Needed for Determining Staffing Needs and Monitoring Access to Care. United States Government Accountability Office; 2022. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105152.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2022

- Military Child Care: Coast Guard Is Taking Steps to Increase Access for Families. United States Government Accountability Office; 2022. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105262.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2022.

- Freeman RE, Thaker H, Daley MF, Glanz JM, Newcomer SR. Vaccine timeliness and prevalence of under vaccination patterns in children ages 0-19 months, U.S., National Immunization Survey-Child 2017. Vaccine. 2022;40(5):765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.12.037

- Deerin JF, Clifton R, Elmi A, Lewis PE, Kuo I. Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination patterns in the military health System, 2014-2018. Vaccine. 2021;39(15):2094-2102. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.010