Abstract

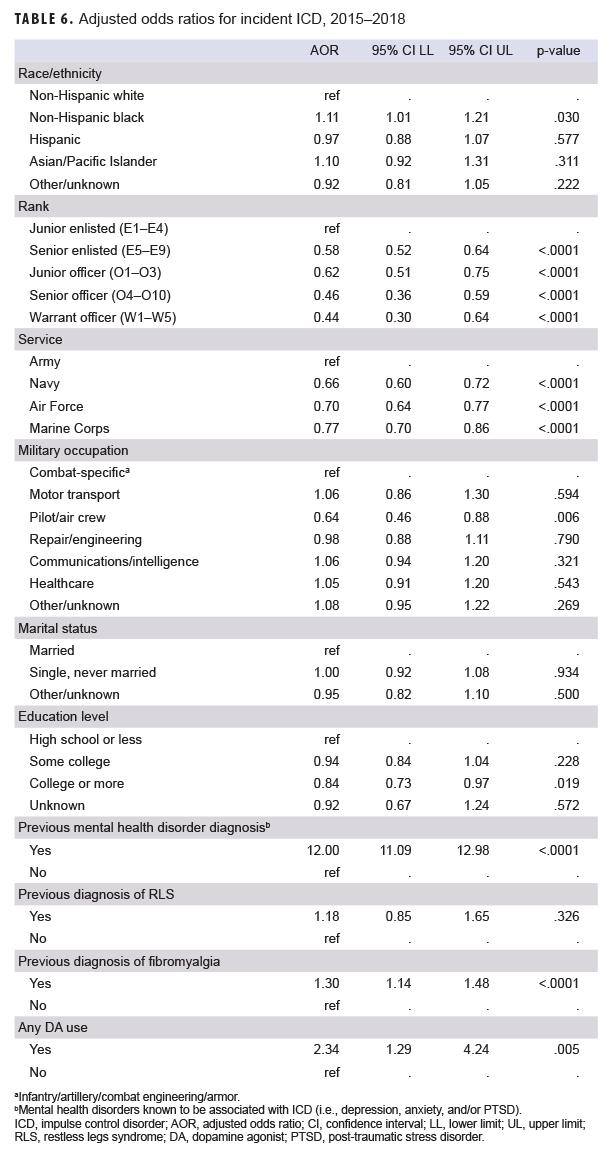

Impulse control disorders (ICDs) are a group of behavioral disorders characterized by failure to resist impulsive thoughts and behaviors that can lead to significant adverse social, legal, and financial consequences. ICDs have been associated with previous diagnoses of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder and have been widely recognized as an adverse effect of dopamine agonist (DA) therapy. The epidemiology of these disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces is unknown. The current study evaluated the incidence of ICD diagnoses in the U.S. Armed Forces during 2014–2018. The overall incidence was 13.7 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs), with the highest rates among females and younger personnel. The current case-control study evaluated the association between DA exposure in the year preceding an incident ICD diagnosis. Although few individuals had received DA therapy in the past year, DA therapy was independently associated with incident ICD diagnosis (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=2.34; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.29–4.24, p<.0001). Previous mental health disorder diagnosis (AOR=12.00; 95% CI: 11.09–12.98, p<.0001) and fibromyalgia (AOR=1.30; 95% CI: 1.14–1.48, p<.0001) were also associated with incident ICD diagnosis. The impact of ICDs on mission readiness, medical evacuation, and deployability should be further evaluated.

What Are the New Findings?

This is the first MSMR report focused on the epidemiology of ICDs in the U.S. Armed Forces. During 2014–2018, there were 8,868 incident cases of ICDs among active component service members, with a crude overall incidence rate of 13.7 cases per 10,000 p-yrs. ICD diagnosis was independently associated with several factors, including any DA prescription, previous mental health disorder diagnosis (depression, anxiety, and/or post-traumatic stress disorder), history of fibromyalgia, junior enlisted military rank/grade, and U.S. Army service.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

There were only 43 ICD cases and 40 controls that had received any DA in the past year, indicating that DA exposure alone does not account for a large number of ICD cases in the military. Given the high prevalence of mental health disorder diagnoses and fibromyalgia among active component service members, it is important that clinicians screen for ICDs during clinical encounters, particularly when considering DA therapy for any diagnosis. Clinicians should also consider regularly screening for development of ICDs after starting DA therapy.

Background

Impulse control disorders (ICDs) are a heterogeneous group of behavioral disorders characterized by the failure to resist impulsive thoughts and behaviors.1 ICDs are phenotypically diverse and can manifest as pathologic gambling, compulsive shopping, compulsive eating, and compulsive sexual behavior (including compulsive hypersexuality, frotteurism, exhibitionism, voyeurism, and other behaviors). Symptoms typically begin insidiously, and patients and family members often fail to recognize them because patients tend to conceal or deny these behaviors.2 ICDs have been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), poor sleep, increased depression and anxiety, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, novelty seeking, poor quality of life, and non-suicidal self-injury and can also lead to serious psychological, social, legal, and financial consequences.3–8

While ICDs are associated with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD,3,9 the use of dopamine agonist (DA) therapy represents a primary risk factor for ICDs. DA-associated ICDs have been most widely recognized in Parkinson disease1,5,6,10–13 but have also been recognized as a consequence of DA therapy for restless legs syndrome (RLS),14,15 prolactinoma,16 fibromyalgia,17 progressive supranuclear palsy,18,19 and multiple system atrophy.20,21

Conditions associated with the diagnosis of ICDs, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, are prevalent in the U.S. Armed Forces.22 In addition, conditions treated with DA therapy, such as fibromyalgia and RLS, are also common (RLS crude incidence=0.96 per 1,000 person-years [p-yrs]; unpublished Defense Medical Epidemiology Database query, March 2019).23 Because of the potentially serious psychological, social, legal, and financial consequences of ICDs, including interference with combat support through non-deployability, medical evacuation, and suicidality, these disorders represent an important unexplored field of study in military populations.

The epidemiology of ICDs in the U.S. Armed Forces is currently unknown, and the degree to which these disorders are associated with DA exposure is also unknown. The current study assessed the epidemiology of ICDs among active component service members by first describing the incidence rate of ICD diagnosis in this population between 2014 and 2018 and then by testing for any associations between incident ICD diagnosis and prior exposure to DA therapy.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which is a relational administrative database of medical events and personal characteristics maintained by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch (AFHSB). The DMSS contains records documenting ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System [MHS]) treatment facilities worldwide. In-theater diagnoses are also available in the Theater Medical Data Store, which was incorporated into the DMSS in 2008.

A retrospective cohort study was used to assess the incidence of ICD diagnoses among active component service members in the U.S Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps between 1 Jan. 2014 and 31 Dec. 2018. An incident case of ICD was defined as a single occurrence of any of the qualifying International Classification of Diseases, 9th or 10th revision (ICD-9 or ICD-10) diagnosis codes in any diagnostic position of a record of an encounter in an inpatient, outpatient, or theater setting (Table 1). An individual was counted as an incident case of ICD only once per lifetime, and individuals who met the criteria for an incident case that occurred before the start of the study period were excluded. Person-time was censored at the time of the incident case diagnosis. Crude incidence was calculated as incidence per 10,000 p-yrs and was stratified by sex, age, race/ethnicity, military rank/grade, branch of service, primary occupational category, marital status, and level of education.

The association between DA exposure and incident ICD diagnosis was assessed using a case-control study design. Subjects meeting the case definition of ICDs described above were included in the case cohort. Four age- and sex-matched controls were selected from the study population of active component service members who were in service at the time the case patient was diagnosed with an incident ICD. The date of incident ICD diagnosis was considered the reference date. Age was matched within 1 year based on age at the reference date. Because controls were sampled from the population at risk at the time of the case diagnosis, it was possible for a control to become a case later and to be included in the study as both a case and control. In addition, it was possible to be selected as a control in the study more than once if the control was selected again for another case.

Previous mental health disorder diagnoses known to be associated with ICDs (i.e., depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD) and conditions treated with DA therapy (Parkinson disease, RLS, prolactinoma, and fibromyalgia) were included as covariates. For each case and control, history of prior diagnosis of depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD was ascertained using the standard AFHSB case definition.24 An individual was defined as having a previous mental health disorder diagnosis if they were diagnosed as an incident case of depression, anxiety, or PTSD at any time before the reference date. In addition, individuals were identified as having a prior diagnosis of Parkinson disease (ICD-9: 332.0; ICD-10: G20), RLS (ICD-9: 333.94; ICD-10: G25.81), prolactinoma (ICD-9: 227.3; ICD-10: D35.2), or fibromyalgia (ICD-9: 729.1; ICD-10: M79.7) if they had a qualifying diagnosis in any inpatient, outpatient, or theater medical encounter at any time before the reference date.

DA exposure was defined as the presence of a prescription for a DA at any point during the 1-year period before the ICD diagnosis. In order to have a complete 1-year observation period, cases and controls were restricted to individuals who had at least 1 year of continuous active duty service before the incident ICD diagnosis. Therefore, cases of ICD were selected between 1 Jan. 2015 and 31 Dec. 2018 to allow for the minimum 1-year observation time.

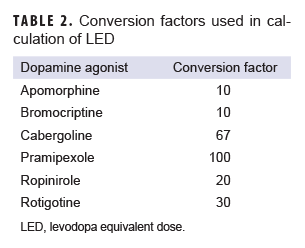

In order to standardize comparison of DA exposure, DA prescriptions were converted into the levodopa equivalent dose (LED) using conversion factors previously described by Tomlinson and colleagues.25 LED was calculated as follows, and the conversion factor for each DA is shown in Table 2.

Rxquantity(number of tablets) x xdose(mg) x Cf(DA)

=Total LED (mg/100mg levodopa)

Total LEDs were summed for the 1-year observation period to compare degree of DA exposure.

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a conditional multivariable logistic regression model to compare the relationship between DA exposure and incident diagnosis of ICDs. The Wald chi-square test was applied using conditional crude logistic regression models for bivariate analyses. Covariates for the multivariable model included sex, age, race/ethnicity, military rank/grade, service, primary occupational category, marital status, and level of education. Because of the large sample size, a p value of .01 was selected as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

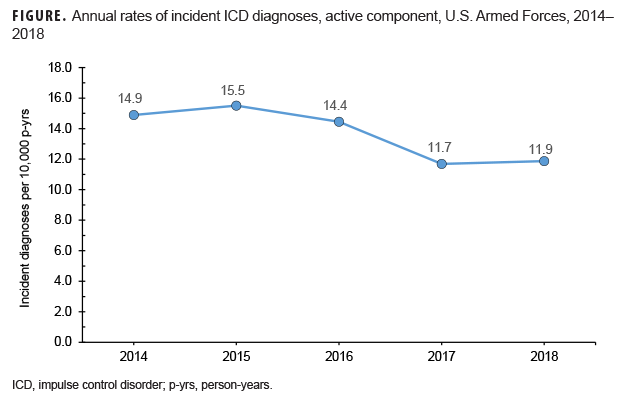

Incidence of ICDs

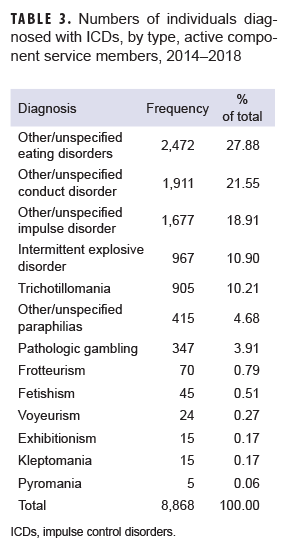

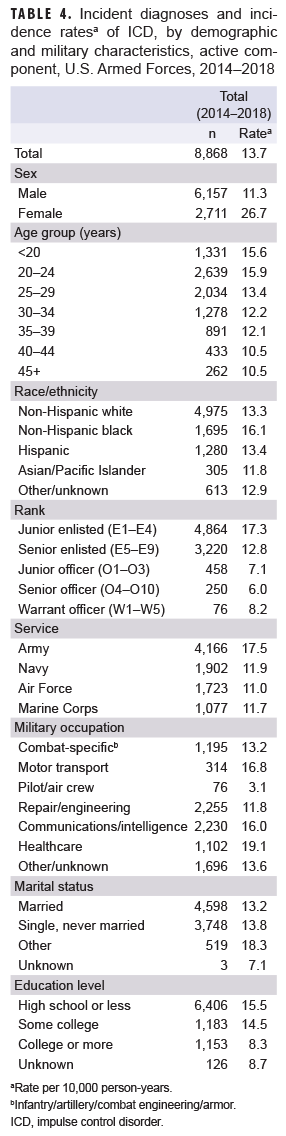

During 2014–2018, there were 8,868 incident cases of ICDs among active component service members, with a crude overall incidence rate of 13.7 cases per 10,000 p-yrs. The most common ICDs were eating disorders (2,472 cases), followed by other/unspecified conduct disorder (1,911 cases), and other/unspecified impulse disorder (1,677 cases). The frequencies of ICDs by diagnosis are shown in Table 3. Crude stratified incidence rates for selected covariates are shown in Table 4. During the 5-year surveillance period, the crude overall incidence rate was highest in 2015 (15.5 per 10,000 p-yrs) and lowest in 2017 (11.7 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Figure). The crude overall incidence rate among females was 2.4 times the rate among males (26.7 vs 11.3 per 10,000 p-yrs). The highest overall rates were seen among service members in the youngest age groups (less than 20 years old, 15.6 per 10,000 p-yrs; 20–24 years old, 15.9 per 10,000 p-yrs), and the lowest overall rates were seen among service members in the oldest age groups (40–44 years old and 45+: 10.5 cases per 10,000 p-yrs). Rates were highest among non-Hispanic blacks (16.1 per 10,000 p-yrs) and lowest among Asian/Pacific Islanders (11.8 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 4).

Compared to other service branches, overall rates of incident ICD diagnoses were highest among those in the Army (17.5 per 10,000 p-yrs) and lowest among those in the Air Force (11.0 per 10,000 p-yrs). Rates among Navy and Marine Corps service members were similar (11.9 vs 11.7 per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively). Rates were higher among enlisted personnel compared to officers, with the highest rates among junior enlisted (17.3 per 10,000 p-yrs) and the lowest among senior officers (6.0 per 10,000 p-yrs). With regards to primary occupational category, health care workers had over 6 times the overall rate of incident ICD diagnoses compared to those working as pilots/air crew (19.1 vs 3.1 per 10,000 p-yrs). Overall incidence rates of ICD diagnoses were higher among service members with "other" marital status (which includes divorced and widowed) compared to those who were married or those who were single and never married. Finally, higher overall rates were seen among those with lower levels of education compared to those with higher levels of education (15.5 per 10,000 p-yrs among those with high school or less compared to 8.3 among those with college education or more).

Association with DA exposure

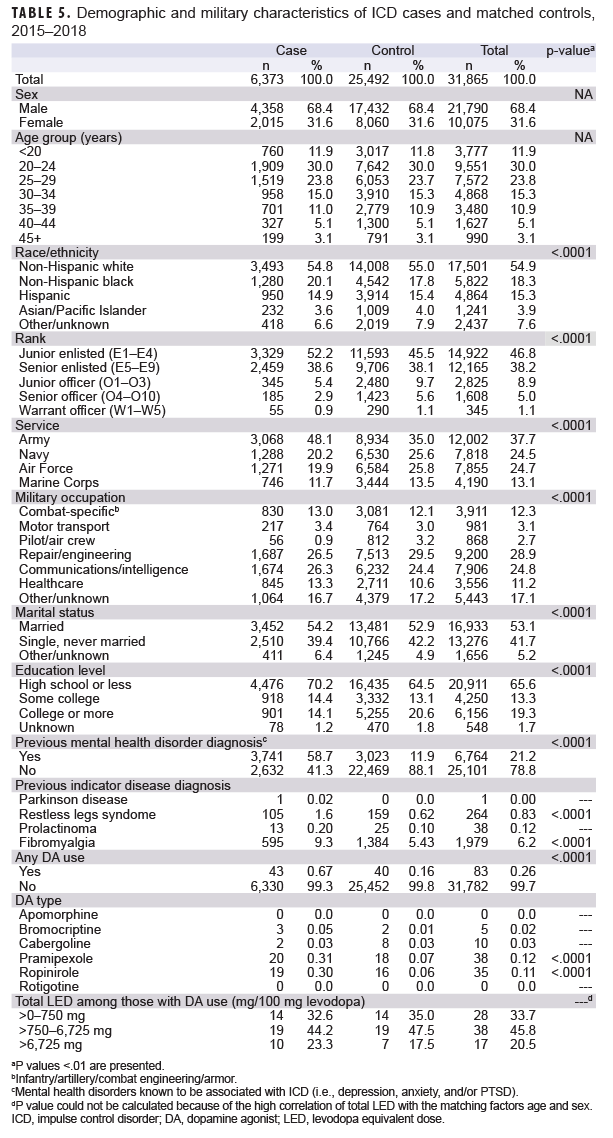

A total of 6,373 cases and 25,492 controls were included in the case-control analysis (Table 5). Overall, a higher proportion of cases had histories of mental health disorder diagnoses known to be associated with ICDs compared to controls (p<.0001). There was a higher proportion of cases with a history of RLS compared to controls (p<.0001), and the same was true for fibromyalgia (p<.0001).

Of the 6,373 impulse disorder cases, 43 had received DA therapy prescriptions within the past year. Of the 25,492 controls, 40 had received DA therapy prescriptions within the past year. Cases had a higher percentage of DA therapy prescriptions compared to controls (0.67% vs 0.16%, respectively, p<.0001). Compared to controls, those who received DAs had a significantly higher frequency of prescriptions for pramipexole (20/6,373 compared to 18/25,492, respectively, p<.0001) and ropinirole (19/6,373 compared to 16/25,492, respectively, p<.0001) (Table 5). Among those prescribed DA therapy within the last year, the frequency distributions of total LED were similar among cases and controls.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed significant associations between ICD diagnosis and previous mental health disorder diagnosis (AOR=12.00; 95% CI, 11.09–12.98; p<.0001) as well as between ICD diagnosis and previous diagnosis of fibromyalgia (AOR=1.30; 95% CI, 1.14–1.48; p<.0001) (Table 6). After controlling for covariates, the association between previous diagnosis of RLS and subsequent ICD diagnosis was not statistically significant (AOR=1.18; 95% CI, 0.85–1.65; p=.326). Finally, analysis revealed that any DA use was significantly associated with an ICD diagnosis after controlling for covariates (AOR=2.34; 95% CI: 1.29–4.24). Parkinson disease and prolactinoma were not included in the multivariate logistic regression model because of a limited number of cases and lack of statistical significance in the bivariate analyses.

Editorial Comment

Many studies have evaluated the prevalence of ICDs among patients with certain conditions such as Parkinson disease. The prevalence of ICDs in Parkinson disease has been observed to be between 2–39% and is highest among patients taking DAs.10 In the general adult population, ICD prevalence is estimated to be between 2–8%.26 However, incidence of ICDs in the U.S. military has not been previously described.

Compared to other mental health disorders among active component service members, the overall incidence of ICDs (13.7 per 10,000 p-yrs) is similar to that of bipolar disorder (15.9 per 10,000 p-yrs).22 By contrast, ICDs occur less frequently than adjustment disorders (420.1 per 10,000 p-yrs), depressive disorders (242.5 per 10,000 p-yrs), and anxiety disorders (212.0 per 10,000 p-yrs) but more frequently than psychotic disorders (9.3 per 10,000 p-yrs) and schizophrenia (2.3 per 10,000 p-yrs).22

Similar to previous studies, this analysis of U.S. military personnel demonstrates that diagnosis of ICDs tends to occur among younger individuals. The highest overall incidence of ICD diagnoses occurred among service members in the Army, which is similar to what has been observed with respect to the overall incidence of many mental health disorders.22 However, it is unclear the degree to which other factors, such as deployment history (which has been shown to be highly associated with mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD) may confound this observation.22

Where previous studies have observed a male predominance of ICD diagnosis, particularly in Parkinson disease,1 this study demonstrated a female predominance among ICD cases. This finding may be accounted for by the high number of eating disorder cases among female active component service members.27

The association between DA exposure and ICD diagnosis has been widely studied in patients with Parkinson disease and other conditions, such as prolactinoma, fibromyalgia, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multiple system atrophy. However, this study examined the relationship between DA exposure and incident ICD diagnosis independently of the condition for which DA therapy was prescribed. DA use was independently associated with ICD diagnosis, even after controlling for other factors in the model (AOR=2.34; 95% CI: 1.29–4.24). However, there were only 43 cases and 40 controls that had received any DA in the past year, indicating that DA exposure alone does not account for a large number of ICD cases in the military.

Similar to previous studies, this report demonstrated a higher association of ICDs with pramipexole and ropinirole therapy compared to other DAs. This may be due to the D3-preferring receptor binding profile of these agents compared to other DAs, which has been suggested from previous studies.12 Larger sample sizes may help to further elucidate this relationship.

The strongest independent association with ICD diagnosis was with previous mental health disorder diagnosis. This suggests that among active component service members, ICDs are more likely to occur in association with previous mental health disorder diagnosis than with DA therapy. Fibromyalgia was also independently associated with ICD diagnosis in the current study. These findings are particularly important for the U.S. military population, in which these disorders are common. Future studies may be helpful in further elucidating the relationship between specific mental health disorder diagnoses and the diagnosis of ICDs.

Finally, the degree to which RLS represents an independent risk factor for ICD diagnosis is a topic of ongoing study in the field of neurology. While the current analysis revealed a statistically significant bivariate association between RLS and ICD diagnosis, this finding did not remain after adjustment for covariates, suggesting that RLS may not be an independent risk factor for ICD diagnosis.

There are several limitations to this study. First, because ICDs are likely underrecognized and underdiagnosed, the incidence data reported here are likely an underestimate of the true burden of these conditions. Moreover, this lack of recognition of patients' ICDs represents a potential source of outcome misclassification bias in this study, as patients who had unrecognized ICDs may have been classified as controls or not included in the case cohort. In addition, retrospective analysis using diagnostic codes limits the ability to detect certain subtypes of mild ICDs, such as punding, hypercreativity, or excessive hobbyism, which are commonly recognized DA-associated ICDs. Similar to other studies involving database queries, provider miscoding is a potential source of misclassification bias.

Retrospective data analysis also limits adequate assessment of cumulative DA exposure before the study period, as prescription data were only available in the DMSS beginning in 2014. Calculation of LED was performed in order to standardize the assessment of DA exposure during the year before ICD diagnosis. However, degree of medication compliance and prescription discontinuation are not known and therefore not represented in the present analysis. Finally, although many potential confounders were adjusted for, uncontrolled confounding cannot be ruled out, specifically with regards to other mental health disorder diagnoses.

ICD diagnosis was independently associated with several factors in this study, including any DA prescription, previous mental health disorder diagnosis (depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD), history of fibromyalgia, junior enlisted military rank/grade, and U.S. Army service. Given the high prevalence of mental health disorder diagnosis and fibromyalgia among active component service members,22,23 it is important that clinicians screen for ICDs during clinical encounters, particularly when considering DA therapy for any diagnosis. Clinicians should also consider regularly screening for development of ICDs after starting DA therapy, as has been previously suggested.28 Additional research exploring the impact of these conditions on medical readiness, medical evacuation, deployability, and mission accomplishment is warranted.

Author affiliations: Department of Neurology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD (LT Garrett), Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Bazaco, CDR Clausen, Ms. Oetting, Dr. Stahlman)

References

- Corvol J, Artaud F, Cormier-Dequaire F, et al. Longitudinal analysis of impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018;91(3):e189–e201.

- Cossu G, Rinaldi R, Colosimo C. The rise and fall of impulse control behavior disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;46(suppl 1):s24–s29.

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: examing associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(3):453–458.

- Antonini A, Barone P, Bonuccelli U, Annoni K, Asgharnejad M, Stanzione P. ICARUS study: prevalence and clinical features of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(4):317–324.

- Voon V, Sohr M, Lang AE, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a multicenter casecontrol study. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(6):986–996.

- Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):589–595.

- Baer MM, LaCroix JM, Browne JC, et al. Impulse control difficulties while distressed: a facet of emotion dysregulation links to non-suicidal self-injury among psychiatric inpatients at military treatment facilities. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:419–424.

- Leppink EW, Lust K, Grant JE. Depression in university students: associations with impulse control disorders. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(3):146–150.

- Grant JE, Levine L, Kim D, Potenza MN. Impulse control disorders in adult psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2184–2188.

- Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(1):5–11.

- Weintraub D, Siderowf AD, Potenza MN, et al. Dopamine agonist use is associated with impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(7):969–973.

- Grall-Bronnec M, Victorri-Vigneau C, Donnio Y, et al. Dopamine agonists and impulse control disorders: a complex association. Drug Saf. 2018;41:19–75.

- Bastiaens J, Dorfman BJ, Christos PJ, Nirenberg MJ. Propsective cohort study of impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28(3):327–333.

- Cornelius JR, Tippmann-Peikert M, Slocumb NL, Frerichs CF, Silber MH. Impulse control disorders with the use of dopaminergic agents in restless legs syndrome: a case-control study. Sleep. 2010;33(1):81–87.

- Heim B, Djamshidian A, Heidbreder A, et al. Augmentation and impulsive behaviors in restless legs syndrome: coexistence or association? Neurology. 2016;87(1):36–40.

- Bancos I, Nannenga MR, Bostwick JM, Silber MH, Erickson D, Nippoldt TB. Impulse control disorders in patients with dopamine agonist-treated prolactinomas and non-functioning pituitary adenomas: a case-control study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80(6):863–868.

- Holman AJ. Impulse control disorder behaviors associated with pramipexole used to treat fibromyalgia. J Gambl Stud. 2009;25(3):425–431.

- Kim YY, Park HY, Kim JM, Kim KW. Pathological hypersexuality induced by dopamine replacement therapy in a patient with progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20(4):496–497.

- O'Sullivan SS, Djamshidian A, Ahmed Z, et al. Impulsive-compulsive spectrum behaviors in pathologically confirmed progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord. 2010;25(5):638–642.

- Klos KJ, Bower JH, Josephs KA, Matsumoto JY, Ahlskog JE. Pathological hypersexuality predominantly linked to adjuvant dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11(6):381–386.

- McKeon A, Josephs KA, Klos KJ, et al. Unusual compulsive behaviors primarily related to dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(8):516–519.

- Stahlman S, Oetting AA. Mental health disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. armed forces, 2007–2016. MSMR. 2018;25(3):2–11.

- D'Aoust RF, Rossiter AG, Elliott A, Ji M, Lengacher C, Groer M. Women veterans, a population at risk for fibromyalgia: the associations between fibromyalgia, symptoms, and quality of life. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1828–e1835.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance Case Definitions. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Epidemiologyand-Analysis/Surveillance-Case-Definitions. Accessed 13 March 2019.

- Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(15):2649–2653.

- Dell'Osso B, Altamura AC, Allen A, Marazziti D, Hollander E. Epidemiologic and clinical updates on impulse control disorders: a critical review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(8):464–475.

- Williams VF, Stahlman S, Taubman SB. Diagnoses of eating disorders, active component service members, U.S. armed forces, 2013–2017. MSMR. 2018;25(6):18–25.

- Mestre TA, Strafella AP, Thomsen T, Voon V, Miyasaki J. Diagnosis and treatment of impulse control disorders in patients with movement disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6(3):175–188.